Thus the blues – ‘the black slave lament’ – was offered up for the admiration of the oppressors.

Frantz Fanon, ‘Racism and Culture’ (1956) in Toward the African Revolution, trans. Haakon Chevalier (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970), p. 47.

A Bard’s Ransom

It is curious, as Stephen Mullen recently observed, that Robert Burns – who never went to Jamaica – has somehow come to stand in for the thousands of Scots who did in the second half of the eighteenth century.1 Yet it is perhaps not surprising given the way Burns (to an extent hardly matched by any other poet) has been regularly hauled before the court of critical opinion and questioned about his life choices.2 Even tributes to Burns are typically expected to begin by admitting his (moral or political) shortcomings before dwelling more extensively on his (literary) talents. That he even contemplated going to the West Indies – and in a letter rather flippantly imagining an alternative future as a ‘poor Negro driver’3 – has been enough for many to channel disquiet about a vast and enduring transatlantic system onto a single, celebrated individual.

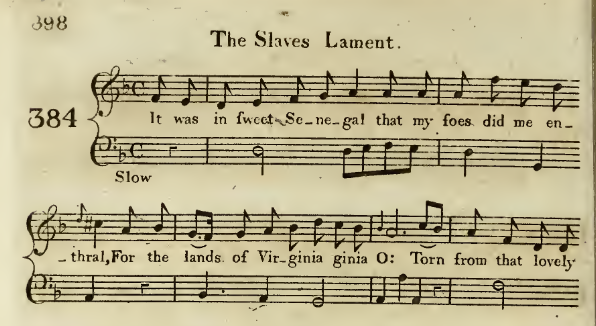

At some point in the legal proceedings, someone is bound to step up in Burns’ defence waving Exhibit A. And just as – in the wider historical debate – any claim that Scotland was complicit in the development and expansion of colonial slavery is often met with the counter-claim that, ‘Ah yes, but we also abolished it,’ so the case for the poet’s prosecution is supposed to collapse in the face of ‘The Slave’s Lament’, the song he is believed to have composed, and which was first published in 1792.

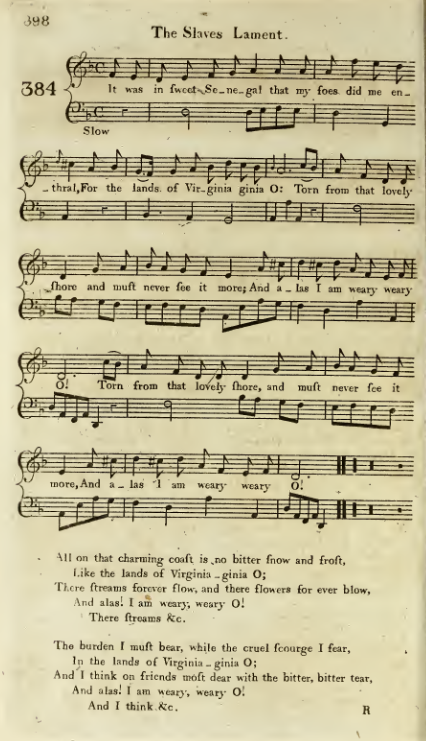

It was in sweet Senegal that my foes did me enthral,

For the lands of Virginia ginia O:

Torn from that lovely shore and must never see it more;

And alas I am weary weary O!

All on that charming coast is no bitter snow and frost,

Lie the lands of Virginia ginia O;

There streams forever flow, and there flowers for ever blow,

And alas I am weary weary O!

The burden I must bear, while the cruel scourge I fear,

In the lands of Virginia ginia O;

And I think on friends most dear with the bitter, bitter tear,

And alas I am weary weary O!

The song appeared in the fourth volume of the six-volume collection, The Scots Musical Museum, put together by the Edinburgh engraver and music-seller James Johnson.4 It’s a moving lyric, to be sure, written from the point of view of one captured in West Africa to be enslaved in North America, bearing the burden while mourning the separation from loved ones back home. And it is regularly cited as a ‘get-out clause’ in response to those troubled by Burns’ colonial intentions.5 He was an abolitionist after all, they say. For many readers and listeners, then, the song itself seems to bear a burden: their own longings for something that offers, in Carla Sassi’s striking phrase, ‘a possibility of ransom from Scotland’s history’s darkest chapter.’6

Whose Song is it Anyway?

If ‘The Slave’s Lament’ is a ransom payment, the recipient might well feel short-changed. Set alongside other abolitionist verse of the period, the song – arguably – resembles less those that celebrate resistance than those that represent the enslaved ‘as helpless and supplicating’.7 Its model seems much closer to Wedgwood’s famous medallion, described by Marcus Wood as ‘the central icon of slave passivity and disempowerment’8 (distributed in Scotland the year the song was published)9 than, say, the statue of the Marron inconnu that stands in Port-au-Prince marking the Haitian revolution (which began the year before).

Michael Morris, in his sustained interrogation of Burns’ relationship to slavery and abolitionism, contrasts ‘The Slave’s Lament’ with Slavery: An Essay in Verse, a passionate twenty-page denunciation of the plantation system written by Burns’ exact contemporary, John Marjoribanks from Kelso who did go to Jamaica and served there as an infantry officer.10 No wonder then that Gerry Carruthers has dismissed it as ‘tame’ and ‘insipid’11 and as a single, ‘solitary item serves only to highlight how little interest [Burns] took in the pro-abolitionist cause, unlike many other Whigs of radical bent during the period.’12

But if this relies on a rather narrow model of what ‘radical’ poetry or song is, the ‘ransom’ falls short in another way. For evidence for Burns having written the song is weak. Carruthers suggests that ‘it is possible that Burns merely collected the song when scraping the barrel to send Johnson material’.13 Nigel Leask concurs: ‘Unfortunately there is no sure evidence that the song was written, rather than collected by Burns.’14 In this they follow editors James Kinsley, who notes that Burns’s ‘part in this song is uncertain’, and Donald Low, who cautiously remarks that it is ‘possibly not his work.’15

When James Currie (another Scot who ‘nearly went to Jamaica’, in his case as a surgeon)16 was leafing through the hundreds of songs Burns supplied to the Museum he may have paused when he came across ‘The Slave’s Lament’, not least because he himself had composed, with William Roscoe, a song they originally entitled ‘The Negroe’s Complaint’ (published pseudonymously as ‘The African’ in 1788).17 But he chose not to include it among the several dozen songs in the Works of Robert Burns he published in 1800.18 He may have had doubts regarding its authorship. More decisively, it may have lacked what Currie believed were the distinctive features of Burns’s songs, which, for him, typically depicted scenes of rural courtship in recognisably Scottish settings.19 And for many years, nothing more was claimed for the song than (as William Stenhouse remarked in his notes to the 1839 edition) it was ‘communicated by Burns to the Museum.’20

As far as I know, the first time it was included in collections of the poet’s works was in the Life and Works compiled by Robert Chambers in 1851, but even then it was, as it were, quarantined in a section entitled ‘Old Songs Improved by Burns from Johnson’s Museum’ and Chambers acknowledges the reluctance to ‘assign this song to Burns’. However, he believes that ‘his authorship of it is much fortified by its resemblance to another song of his, entitled The Ruined Farmer’s Lament, which seems to have been formed on the same model.’21 The resemblance is slight, but it helped to shoe ‘The Slave’s Lament’ into the Burns canon, and the song regularly appears in editions of his works thereafter.

During this period of relative anonymity, it is worth dwelling on the note on the song Allan Cunningham inserts in his Songs of Scotland, Ancient and Modern of 1825:

Of the author of this sweet song I can give no account. It is generally believed to be expressed in something like the simple language of that hapless race who were for so many centuries condemned by European avarice to perpetual slavery. The air too is supposed to be of African extraction. Indeed, the slaves in the West Indies have a remarkable taste for music; and every step they take, and every task they perform, is accompanied by song.22

By emphasising the uncertain origin of ‘The Slave’s Lament’, Cunningham is able to coax the reader who might skip over his qualifications (‘believed to be … supposed to be’) into imagining that it is an authentic slave song, sung not only to an ‘African’ melody but its words ‘too’ originally ‘expressed in … the simple language of that hapless race.’ As if it was based on the transcription of the singing of an actually enslaved person. An untutored cousin of Phillis Wheatley, perhaps, who like her was kidnapped in ‘Senegal’, but ended up in the fields of Virginia rather than the genteel homes of Boston, Massachusetts.23

After all, this period of the song’s anonymity coincides with the rise and fall of anti-slavery activity in Scotland, from Dickson’s tour of 1792 to the visits of Frederick Douglass, William Wells Brown and others in the 1840s and 50s.24 The movement, though best known, especially in Britain, for its white leaders (William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson) prized the testimony of the enslaved, and autobiographical narratives and lecture tours by Black men and women (when appropriately managed) formed an important part of the campaign’s rhetorical armoury. By the middle of the century popular demand for this testimony had fallen considerably, and the travesties of blackface minstrelsy seeped into even ostensibly abolitionist works such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin, particularly the theatrical adaptations that flourished in the decade before the Civil War.

From Poem to Song

Although ‘The Slave’s Lament’ was printed regularly in collections of Burns’ works from the 1850s, editions that included the melody were few and far between and for a long time hard to obtain. The situation improved with the republication of Robert Dick’s Songs of Robert Burns (1903) in 196225 and the appearance of Kinsley’s edition of the Poems and Songs in 1968, but the song never entered the repertoire of those renowned for their interpretation of Scots song for another two decades.

Only after Jean Redpath recorded it in 1981 as part of the ambitious Burns song project of Serge Hovey – based on many years’ research and featuring finely-crafted arrangements26 – did other singers begin to take notice.27

Versions of ‘The Slave’s Lament’ were recorded by Dougie MacLean (1991), Sheena Wellington (1995), Christine Kydd (solo for the Complete Songs of Robert Burns, 1995 and with Chantan 1997), Tam White (2003), Karine Polwart (2005), Battlefield Band (2006) and many more. (See this playlist for a selection.) In a documentary made during her visit to Scotland for the Burns Bicentenary in 1996, Maya Angelou said the song was ‘a perfect example of how a poet transcends race, time and space.’28

The song no doubt acquired new listeners when it featured in various art installations by Graham Fagen, which explored historical connections between Scotland and the Caribbean. Perhaps best known is the exhibit made for the Venice Biennale in 2015 (subsequently touring widely) which included a video projection of a specially-arranged string version by the composer Sally Beamish with the reggae singer Ghetto Priest.

All this not only put the song into much wider circulation, but also cemented its association with Robert Burns who is typically identified unproblematically as the author in the accompanying material. Sometimes this has been assisted by (unsupported) anecdotal claims that Burns wrote the song after seeing a slave ship in Dundee – a story heard by Sheena Wellington and printed in the sleeve notes to the live album on which her recorded version appears.29

Return to Source: The New Oxford Burns

By the first decade of this century, ‘The Slave’s Lament’ was pretty well established as a Burns song. Scholars would occasionally warn that the evidence of authorship was by no means settled, but their voices were seldom heard.

And now, with the new edition of the Scots Musical Museum, forming Volumes II and III of the recent Oxford Edition of the Works of Robert Burns (2018) perhaps they may be definitively silenced. For this edition Murray Pittock adopted an eight-fold system of classification (I to VIII) in an attempt to establish the degree to which Burns was involved as author and editor of each song. ‘The Slave’s Lament’ he assigns to ‘Category I [‘A song wholly by Burns, with no prior antecedents identified, or suspected’)] or Category III [‘A song significantly by Burns, with only isolated lines or a combination of phrases, subject matter, and tune evident from earlier evidence’’]’.30

That ‘Category I’ is considered a possibility is curious given that most of the editorial note that ends with this categorisation is concerned precisely with ‘prior antecedents’ of the song. As indeed Pittock (and the editors before him) does with most of the songs in the Museum, demonstrating that they did not spontaneously erupt from the imagination of the poet but were born of protracted immersion in the song culture of the eighteenth century, both in print (studying chapbooks, broadsides and bound collections) and orally (learning songs and tunes he heard sung and played by people he knew or met, either close to home or on his travels round the country).

In the case of ‘The Slave’s Lament’ the earliest attempt to identify an antecedent was by Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe in the 1839 edition of the Museum where he writes: ‘I believe that Burns took the idea of his verses from “the Betrayed Maid,” a ballad formerly much hawked about in Scotland’, which he transcribes ‘from the stall copy’.31 A few decades later, the editors of The Poetry of Robert Burns (1897) added: ‘But Sharpe had no direct proof that this “stall copy” was older than the Burns. It may be that older it is, and that Burns used it; but the original is certainly a blackletter broadside, The Trappan’d Maiden, or The Distressed Damsel’.32 That this was an important source for ‘The Slave’s Lament’ would seem to be confirmed by both Dick (1903) and Kinsley (1968) and in the new Oxford Edition Pittock finds it a ‘plausible’ claim.33

’The Trappan’d Maiden’ – facsimiles of copies dating from the late seventeenth / early eighteenth century may be viewed in the English Broadside Ballad Archive and the Bodleian Library’s Broadside Ballads Online – runs to sixteen verses and begins:

Give ear unto a Maid,

That lately was betray’d,

And sent into Virginny O:

In brief I shall declare,

When that I was weary,

Weary, weary, weary, O.

As a first-person tale of enforced exile, and with its rhyme of ‘Virginny O’ and ‘weary O’, the similarities with ‘The Slave’s Lament’ are evident.34 But one striking difference, which no-one had made much of till now, is that the speaker in the broadside ballad is no African. As the prefatory note makes clear, ‘This Girl was cunningly trapann’d / Sent to Virginny from England.’ Pittock’s annotations probe deeper, drawing attention to a variant, ‘The Virginian Maid’s Lament’ included in Ancient Ballads and Songs of the North of Scotland (1828) and the note thereon by Peter Buchan.35 Buchan situates the Lament thus:

The practice of kidnapping, or stealing children from their parents, in the north of Scotland, from 1735 down to 1753, a period of eighteen years inclusive, and selling them for slaves to the planters of Maryland, Virginia, &c in North America, is too notorious to require any illustration here.

But not so notorious to prevent him to going on at great length to narrate the story of Peter Williamson, quoting a long extract from his autobiography.36

That Buchan calls the victims of such practices ‘slaves’ was certainly not exceptional for his time, but the use of the term ‘slavery’ to refer indiscriminately to a wide range of economic, social, political and legal injustices was contested vigorously by those of his contemporaries committed to the struggle to abolish the very particular institution of chattel slavery in the Americas in the nineteenth century. They were all too well aware of the ways in which those who defended that institution were quick to seize on any excuse to deny the unique features of a transcontinental economic system based on human beings made the property of others. There are many who are worse off than the black slave, they would say. In a speech in Paisley in 1846 Frederick Douglass called this use of the term ‘slavery’ an ‘awful misnomer’.37 And it’s a point that needs to be repeated today as the flag of the ‘white slave’ (often ‘Scottish’ and ‘Irish’) is regularly raised in attempts to discredit anti-racist scholarship and activism.38

In the circumstances, then, Pittock’s suggestion that the ballad ‘does not seem to deal with African but with white slavery’ – uncritically adopting the terminology used by Buchan (without even the caution of quotation marks) – is injudicious, to say the least. The smirring of two very different forms of exploitation then makes it easy to dismiss the significance or emotional weight of ‘Senegal’ in the ‘The Slave’s Lament’ itself. Pittock concludes:

The final stanza of the Burns song makes clear that the woman who is lamenting ‘on friends most dear’ sounds more like a Jacobite exile than an African, who has suffered the fate of many of her fellow from the north-east of Scotland in the 1730-60 era, who were trafficked and sold ‘for slaves to the planters.’39

Conclusion: Restoring Strangeness to ‘The Slave’s Lament’

That the words of ‘The Slave’s Lament’ clearly owe something to ballads like ‘The Trapann’d Maiden’ has led editors and others to focus on the similarities rather than the differences, which rather conceals the work of transformation that turned one into the other. And unless we turn up other poems or songs in broadsides or printed collection that more closely resemble the one in the Scots Musical Museum, we must assume with some certainty that this work of transformation was ’significantly by Burns’, as Pittock’s second and more plausible categorisation has it. But why then belittle his input to the replacement of ‘England’ (in ‘The Trapann’d Maiden’) or ‘Scotland’ (in ‘The Virginian Maid’s Lament’) with ‘Senegal’ – and further diminish even this change as superficial by implying that ‘The Slave’s Lament’ is really about the tribulations of the Scottish diaspora, and not ‘about’ (chattel) slavery at all?

Why not both? Why not tease out the friction that comes from rubbing the two worlds of experience together, recognising certain similarities – even the possibilities of solidarity and collective resistance between them40 – without collapsing them in an unhelpful generic all-encompassing ‘slavery’ tag? It is possible to situate the song (as Carol McGuirk does) in the context of other verses by Burns on the theme of involuntary exile in a way that respects its difference: ‘Other exiled hearts speak not across time but from cultures far removed from Scotland’.41

And we might too pay more attention to the relationship between ‘The Slave’s Lament’ and other abolitionist verse of the 1790s – looking at not only differences of form but also of its place in print culture. Not in order to trace lines of influence necessarily but in an attempt to register how – on the page of the Scots Musical Museum – the lyric sounded to contemporary readers, familiar with abolitionist verse and other campaign material. Did they find it ‘in tune with growing and widespread unease’ about the slave trade, debated in the House of Commons at the time, as Robert Crawford suggests?42 Or did it strike a jarring or at least unexpected note?

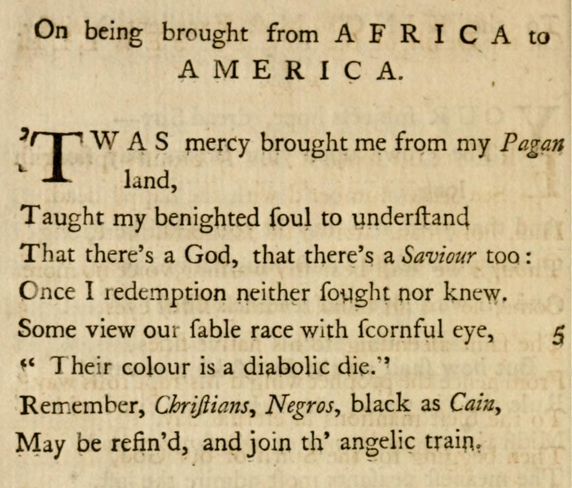

For this reason (and having mentioned Phillis Wheatley earlier) it might be an instructive exercise to place ‘The Slave’s Lament’ alongside to her famous poem. ‘On Being Brought from Africa to America’, first published in her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773).43

’Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

‘Their colour is a diabolic die.’<

Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.

Without making any assumptions that Burns was familiar with the poem, consider how the Middle Passage in one is figured in religious terms (as a journey from paganism to Christianity) in contrast with the dominantly climatic and adversarial frame of reference in the other (as a journey from warm to cold, from ‘friends’ to ‘foes’); the shift from an expression of thanks to what it has made possible to a mourning of what – and who – has been left behind.

But what is more important perhaps is the turn half-way through Wheatley’s poem where the poet switches from narrating a personal experience to name and address her oppressors (‘Remember, Christians’) on behalf of her fellows (‘our sable race’) to vigorously proclaim their collective humanity. There is no corresponding switch in ‘The Slave’s Lament’ which remains in the first person singular throughout. And if the objectified ‘me’ in the first verse becomes a more expressive ‘I’ in the third, it is still an ‘I’ that ‘must bear’ and ‘fear’ the toil and punishments of the plantation, while those who wield the ‘scourge’ are unspecified and therefore unable to be rebuked.

Yet there is something forceful in the closing assertion that the eponymous ‘slave’ is capable of thought and feeling, and perhaps in the many repetitions of ‘I am weary’ in the chorus one might detect a hint of the singer’s frustration at having to tell their story over and over because no-one is really listening. Like Fannie Lou Hamer, ‘sick and tired of being sick and tired.’

As for the tune, the supposition that it was ‘an original African melody’ has been given short shrift by scholars, even if it continues to be repeated in sleeve notes.44 But the fancy did not just emerge from a romantic or abolitionist desire for the authentic or exotic. It does recognise something anomalous about the song – that it sounds different from the others in the Museum. Whether it is its even pacing or its harmonic progressions, the melody has characteristics that set it apart from what is generally felt to be characteristic of Scots song. Martin Carthy reports, when told it was a Burns song on first hearing it, ‘I did think, “Oh yeah?”’

The song chooses to render the experience of slavery as a ‘lament’ rather than as a ‘complaint’, a related but more accusatory genre that was more commonly adopted in abolitionist verse.45 As such it seems to sit comfortably with the half-dozen poems or songs by Burns that have ‘lament’ in their title; and certainly the lament has deep roots in Scottish music. But the genre points us outward too – back to the baroque classical laments and forward (as several interpreters of the song recognise, because they inhabit musical worlds unknown to Burns) to African American spirituals and blues.

So we shouldn’t be so surprised that Serge Hovey thought the tune ‘has all the characteristics of a Jewish lamentation in the Ashkenazic Ahavoh-Rabboh mode.’46 Or that, intriguingly, Sheena Wellington reports meeting in Singapore an ‘anthropologist from Dorset who said […] it’s actually 12th, 13th century Spanish sephardic, “Rachel’s Lamentation”, and they know it in North Africa to a different rhythm’.47

As far as I know this speculation awaits more detailed research. Perhaps there is more in Hovey’s Robert Burns Songbook, 1200 pages of manuscript completed in 1973 that remains in private hands.48 Furthermore, no one has yet found it in any printed collection that Burns might have consulted and any plausible circumstance in which he might have heard someone playing or singing it remains hard to reconstruct.49 This absence is significant because, as Kirsteen McCue has pointed out, the words to the songs he wrote were ‘most often inspired by a melody. Indeed Burns noted that he had to know a tune intimately before beginning to write a lyric for it.’50

There are many unknowns about ‘The Slave’s Lament’. There is so much more to find out. But if we resist the temptation to treat it primarily as evidence to be produced in defence of an individual’s character – or (even worse) to offer it by way of compensation for what has been called ‘Scotland’s hidden shame’ – we are more likely to appreciate the manifold musical, literary and historical forces that have combined to shape and re-shape the song, before and after its appearance in the Scots Musical Museum. It is time to rediscover a certain haunting strangeness in ‘The Slave’s Lament’ that those who perform it often capture so well.

Notes

This is a work in progress (last revised 9 Apr 2021). Comments welcome.

-

- For estimations of figures see Douglas J. Hamilton, Scotland, the Caribbean and the Atlantic World 1750-1820 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005), pp. 22-25.

- ‘The issue of whether the poet was (or was not) an admirable person … places the critic as moral judge in a recurring trial where Robert Burns is perpetual defendant’: Carol McGuirk, ‘The Politics of The Collected Burns,’ Gairfish: Discovery, ed. W.N. Herbert and Richard Price (Bridge of Weir: Gairfish, 1991), p. 36.

- Robert Burns to John Moore, Mauchline, 2 August 1787 in The Letters of Robert Burns, ed. G. Ross Roy (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985), Vol. 1, p. 144.

- ‘The Slave’s Lament’, in The Scots Musical Museum Vol. IV, ed. James Johnson (Edinburgh: Johnson & Co, 1792), p. 398.

- Nigel Leask, ‘“Their Groves o’ Sweet Myrtles”: Robert Burns and the Scottish Colonial Experience’ in Robert Burns in Global Culture, ed. Murray Pittock (Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 2011), p. 178.

- Carla Sassi, ‘Acts of (Un)willed Amnesia: Dis/appearing Figurations of the Caribbean in Post-Union Scottish Literature’ in Caribbean-Scottish Relations : Colonial and Contemporary Inscriptions in History, Language and Literature , ed Giovanna Covi, Joan Anim-Addo, Velma Pollard and Carla Sassi (London: Mango, 2007), p. 172.

- The range of late 18th- and early 19th-century verse is discussed by Alan Richardson in his introduction to his anthology, Slavery, Abolition and Emancipation: Writings in the British Romantic Period, Volume 4: Verse (London: Pickering and Chatto, 1999).

- Marcus Wood, ‘Popular Graphic Images of Slavery in Nineteenth-Century England’ in Representing Slavery: Art, Artefacts and Archives in the Collections of the National Maritime Museum, ed. Douglas Hamilton and Robert J. Blyth (Aldershot: Lund Humphries, 2007), p. 144.

- Iain Whyte, Scotland and the Abolition of Black Slavery, 1756–1838 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006), esp. pp. 74–78.

- Michael Morris, Scotland and the Caribbean, c.1740–1833: Atlantic Archipelagos (New York: Routledge, 2015), pp. 98-131, esp. 115–19. See also Karina Williamson, ‘The Antislavery Poems of John Marjoribanks,’ EnterText, Vol. 7, No. 1 (2007), pp. 60-79.

- Gerard Carruthers, ‘Robert Burns and Slavery’, The Drouth 26 (2007), p. 23.

- Gerard Carruthers, Robert Burns [2006] (Liverpool University Press, 2018), p. 60. Nigel Leask pursues this more fully in ‘“Their Sweet Groves”’.

- Carruthers, ‘Burns and Slavery,’ p. 23

- Leask, ‘“Their Sweet Groves”, p. 178.

- Robert Burns, The Poems and Songs of Robert Burns, ed. James Kinsley (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968),Vol. 3, p. 1405; Robert Burns, The Songs of Robert Burns, ed. Donald Low (London: Routledge, 1993), p. 547.

- Robert Donald Thornton, James Currie: The Entire Stranger and Robert Burns (Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd, 1963), pp. 92–4. As a younger man, however, he was employed as an apprentice by William Cunninghame & Company on their tobacco plantations in Virginia. Ibid., pp. 32–66.

- Thornton, James Currie, p. 191. For the words of the song and further details, see William Wallace Currie, Memoir of the Life, Writings and Correspondence of James Currie, M.D. F.R.S. of Liverpool (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green, 1831), Vol.1, pp. 127–35. It is also reprinted, as ‘The African’, in Richardson, Slavery, Abolition and Emancipation, pp. 99-100.

- James Currie, The Works of Robert Burns; with an account of his life… (Liverpool: J. M’Creery, 1800), 4 vols.

- For Currie’s assessment of Burns’s songs, see esp Works, Vol. 1, pp. 323-30.

- William Stenhouse, ‘Illustrations of the Lyric Poetry and Music of Scotland, Part IV’ in The Scots Musical Museum Vol. IV, ed. James Johnson (Edinburgh: William Blackwood, 1839), p. 353. Stenhouse’s notes were subsequently published separately in 1853.

- Life and Works of Robert Burns, ed. Robert Chambers (Edinburgh: W. and R. Chambers, 1851), Vol. IV, pp. 267–68.

- Allan Cunningham, Songs of Scotland, Ancient and Modern… (London: John Taylor, 1825), 4 vols, Vol. II, pp. 223–24. Fourteen years later Stenhouse repeats the supposition that ‘the air … is an original African melody’, (‘Illustrations,’ p. 353) ensuring that it enjoyed wide circulation.

- Although it is popularly believed that Wheatley came from Senegal or thereabouts, the location of her birthplace or even where she was forced on board the slave-ship, is uncertain. See Vincent Carretta, ‘Phillis Wheatley: Researching a Life,’ Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 43 No. 2 (2015), esp. pp. 70–1.

- The best survey of this activity is Whyte, Scotland and the Abolition of Black Slavery.

- James C. Dick, The Songs of Robert Burns [1903] (Hatboro’, PA: Folklore Associates, 1962).

- See Kirsteen McCue. ‘“Magnetic Attraction”: The Transatlantic Songs of Robert Burns and Serge Hovey.’ in Robert Burns and Transatlantic Culture , ed. Sharon Aiker, Leith Davis and Holly Faith (London: Routledge, 2012), pp. 233-247.

- Sheena Wellington remarked: ‘I first heard the poem from my father when I was about 9 and nearly cried but as “snivelling” was not encouraged in our house I went and learned the poem by heart instead. I don’t think I ever heard a tune to it until Jean Redpath recorded it’. Quoted in Valentina Bold, ‘The Slave’s Lament’, a talk delivered at Wigtown Book Town Festival, 2007, with Kathy Hobkirk performing the song.’, p. 13. This talk is the most detailed study of the song to date, and especially valuable for what it reveals of how singers themselves have responded to ‘The Slave’s Lament.’

- Quoted in Bold, ‘The Slave’s Lament,’ p. 8.

- Sheena Wellington, Strong Women (Greentrax CDTRAX 094) (1995), For further reflections on this story see Bold, ‘The Slave’s Lament’, p. 4.

- The Oxford Edition of the Works of Robert Burns. Vols II and II: The Scots Musical Museum, ed. Murray Pittock (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), Vol. III, p. 142 . The categories themselves are defined in Vol. II, p. 12, where it is stated that only those in Category I through to V ‘deserve a full place in the Burns canon’.

- C. K. Sharpe, ‘Additional Illustrations,’The Scots Musical Museum Vol. IV, ed. James Johnson (Edinburgh: William Blackwood, 1839), pp. 389-91. In some accounts of the history of ‘The Slave’s Lament’ Sharpe is confused with the English folk-song collector Cecil Sharp.

- The Poetry of Robert Burns, ed. William Ernest Henley and Thomas F Henderson (Edinburgh: T C and E C Jack, 1897), Vol. III, p.393.

- The Songs of Robert Burns, ed. James C. Dick (London: Henry Frowde, 1903), p. 479; Robert Burns, The Poems and Songs of Robert Burns, ed. James Kinsley, Vol. 3, p. 1405; The Oxford Edition, Vol. III, p. 141.

- On the recurrent theme of ‘involuntary exiles’ (of all kinds) in Burns poems and songs see Carol McGuirk, ‘The Crone, the Prince, and the Exiled Heart: Burns’s Highlands and Burns’s Scotland’, Studies in Scottish Literature, Vol. 35, No. 1 (2007), pp. 184–201.

- Ancient Ballads and Songs of the North of Scotland, ed. Peter Buchan (Edinburgh: W & D Laing, and J Stevenson, 1828), Vol II, pp. 215-17, 332-35.

- The Life and Curious Adventures of Peter Williamson. New edition. Aberdeen: 1826. The book was first published in Aberdeen in 1801.

- Renfrewshire Advertiser, 28 March 1846.

- See, for example, Stephen Mullen, ‘The Myth of Scottish Slaves’, Sceptical Scot, 4 March 2016; Liam Hogan, ‘“Irish Slaves”: The Convenient Myth’, openDemocracy, 14 January 2015.

- Oxford Edition, Vol. III, p. 141. Note also the assumption that the singer is a woman, casting aside the change from the gendered ‘maid’ or ‘maiden’ to the ungendered ‘slave’.

- See, for example, Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra: The Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic (London: Verso, 2000).

- McGuirk, ‘The Crone, the Prince, and the Exiled Heart,’ p. 199. How ‘far removed’ Senegal and Virginia were ‘from Scotland’ in the 1790s remains an interesting question.

- Robert Crawford, The Bard: Robert Burns, a Biography (London: Pimlico, 2010), p. 352.

- Phillis Wheatley, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (London: A. Bell, 1773), p. 18.

- In 1903 Dick was rather sceptical (Songs of Robert Burns, p. 479); and more recent editors have rubbished the claim as ‘nonsense’ (Kinsley) and ‘ridiculous’ (Pittock).

- ‘Complaint’ appears in the title of several poems – not only Currie and Roscoe’s ‘The Negroe’s Complaint’ (1788) (already mentioned) but also William Cowper’s more famous poem with the same title (1788), and an anonymous ‘The African’s Complaint On Board a Slave Ship’ (1793). But note also ‘The Sorrows of Yamba; or, the Negro Woman’s Lamentation’ (1795), possibly the work of Hannah More. All are reprinted in Richardson, Slavery, Abolition and Emancipation.

- CD booklet, Jean Redpath, The Songs of Robert Burns, Volumes 3 & 4 (Greentrax CDTRAX 115, 1998) (Volume 3 on which ‘The Slave’s Lament’ appears was originally released on LP as Philo 1071 in 1981).

- Quoted in Bold, ‘The Slave’s Lament,’ p. 14.

- McCue. ‘“Magnetic Attraction”’, p. 237.

- The versions of ‘A Trappan’d Maiden’ Burns may have seen were not printed with the melody, and the words would not have fitted the tune in the Museum in any case, so it’s unlikely he came across the melody in that quarter.

- Kirsteen McCue, ‘Burns’s Songs and Poetic Craft,’ The Edinburgh Companion to Robert Burns, ed. Gerard Carruthers (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009), p. 75.

Historic marker at 4th Avenue N and 19th St N, Birmingham, Alabama: photo by

Historic marker at 4th Avenue N and 19th St N, Birmingham, Alabama: photo by