- York Temperance Hotel, 19 Nicolson Street.

- United Secession Church, 19 Rose Street (Rev John McGilchrist)

- Waterloo Rooms, 29 Waterloo Place.

- Music Hall, 54 George Street.

- Brighton Street Chapel.

- 45 Melville Street.

- Council Chambers.

- Theatre Royal.

- 33 Gilmore Place.

- 10 Salisbury Road.

- 5 South Gray Street.

- 7 Montpelier.

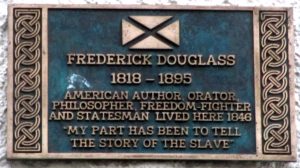

Frederick Douglass loved Edinburgh. ‘It is a beautiful city,’ he wrote, ‘the most beautiful I ever saw – not so much on account of the buildings as on account of its picturesque position.’ He briefly entertained the idea of bringing his family over and settling permanently, but he was soon convinced of the need to return to the United States and rejoin the abolitionist campaign on the front lines. ‘I know it will be hard to endure the kicks and cuffs of the pro-slavery multituude, to which I shall be subjected; but then, I glory in the battle, as well as in the victory.’

He arrived for the first time in April 1846, and embarked on an intense schedule of a dozen or so lectures in the month leading up to the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland that opened at the end of May. He and his fellow campaigners, James Buffum, Henry Clarke Wright and George Thompson, exerted pressure on the church’s leaders to take an unequivocal stand against their Presbyterian counterparts in the United States for their willingness to placate slaveholders. The Assembly was to be the culmination of the ‘Send Back the Money’ campaign. It was even said that Douglass was observed carving the slogan in large letters of the slopes of Arthur’s Seat with ‘two fair Quakeresses’, probably Jane Smeal and her step daughter Eliza Wigham, active members of the Edinburgh Ladies’ Emancipation Society.

With Thomas Chalmers in failing health (he died the following year), it was left to William Cunningham and Robert Candlish to manage the few dissenting voices in the Free Church. The abolitionists attended the Assembly and an outburst from Thompson momentarily disrupted proceedings, but the leadership held firm. Buoyed by vigorous editorials on the issue by Hugh Miller in the Witness, they engineered a compromise that effectively closed the debate.

Disappointed, the campaigners went their own ways from the capital in June to pursue their activities in Ireland and England. But Douglass returned in the autumn with Thompson and William Lloyd Garrison as they looped twice around Scotland, promoting their new venture the Anti-Slavery League. They enjoyed the hospitality of several leading Edinburgh abolitionists including the Wighams, and the Rev. James Robertson, secretary of the Scottish Anti-Slavery Society.

Douglass records meeting several leading figures in the city, including the publishers Robert and William Chambers (who reviewed his Narrative in theirJournal). And he later recalled with fondness his breakfast with phrenologist George Combe, whose best-known work, Douglass claimed, ‘relieved my path of many shadows.’

As elsewhere in Scotland, Douglass found himself competing for audiences with blackface minstrel shows, including crowds who flocked to see the Ethiopian Serenaders, whose tour overlapped with his in Edinburgh in October. He later denounced such performers as ‘the filthy scum of white society, who have stolen from us a complexion denied to them by nature,’ but chose to pointedly ignore them on this occasion.

In his letters from Edinburgh we get rare glimpses of the private Douglass – fatigued by the relentless campaigning and missing his wife Anna and their children. In one of his ‘fits of melancholy’, he tells a family friend, he saw a fiddle for sale in a music shop. He promptly bought it and took it back to his hotel and played a Scots air. ‘I had not played ten minutes before I began to feel better and – gradually I came to myself again and was lively as a crikit and as loving as a lamb.’

|

York Temperance Hotel, 19 Nicolson Street. Advertised as ‘combining the elegance and comfort of a first-rate Hotel with the quiet and home-like character of a genteel family residence’, this was Douglass’s main base when in Edinburgh. The site was subsequently occupied by a number of entertainment venues, most recently the Festival Theatre. |

|

United Secession Church, 19 Rose Street. Douglass spoke here on 28 and 29 April and on 7 May (with Buffum, Thompson and Wright). Letters to the Witness newspaper pointed to the church being a beneficiary of compensation paid to slaveholders in the wake of West Indian Emancipation, suggesting the hypocrisy of the abolitionist campaign’s exclusive focus on the Free Church. |

|

Waterloo Rooms, 29 Waterloo Place. At a ‘Public Breakfast’ on 1 May ‘Mr Douglass especially enchained the attention of his audience,’ according to a report, ‘alternately humorous and grave – argumentative and declamatory – lively and pathetic. None who heard him will ever forget the impression.’ The building is now a restaurant. |

|

Music Hall, 54 George Street. Douglass spoke here numerous times in May and June (with Buffum, Thompson and Wright). On 25 May, ‘the orchestra was crammed from top to bottom, and hung with a galaxy of ladies and gentlemen, like a drop scene of a theatre.’ Built in the 1780s, the grand building, as the Assembly Rooms, remains one of the city’s main venues. |

|

Brighton Street Chapel. Douglass spoke here on 31 July (alone) at a meeting of the Scottish Anti-Slavery Society, and three times in the autumn (with Garrison). In his October speech Douglass told how the previous morning in Liverpool he had encountered a former slave he had known in Baltimore. The church no longer stands, the site now occupied by the National Museum of Scotland. |

|

45 Melville Street. The home of George Combe, the leading British exponent of phrenology. Douglass visited him there (with Buffum and Thompson) on 7 June, Combe noting in a letter that ‘he has an excellent brain’ and praising his eloquent speeches, but expressing reservations about his uncompromising stance towards the Free Church. The building is now occupied by the Information Commissioner’s Office. |

|

Council Chamber. On 6 June, Douglass attended a packed meeting held to confer the freedom of the city on George Thompson in recognition of ‘his exertions in the cause of negro emancipation in the West Indies, and for his advocacy of the abolition of the corn laws.’ In his acceptance speech Thompson diplomatically promised to abstain from referring to the campaign against the Free Church. |

|

Theatre Royal, Shakespeare Square. The Ethiopian Serenaders performed here in October to Douglass’ likely irritation. He would no doubt have preferred to see the African American actor Ira Aldridge in The Black Doctor in April 1847 but by then Douglass was crossing the Atlantic back home. The theatre was demolished in 1860 and the site was later occupied by the city’s main post office, now converted to offices. |

|

33 Gilmore Place. Douglass stayed here at the end of July and possibly on other occasions. This was the home of James Robertson, secretary of the Scottish Anti-Slavery Society, a body formed that summer in an attempt to unify the various strands of Scottish abolitionism. Robertson spoke alongside Douglass and Garrison at several of their autumn engagements in Scotland. |

|

10 Salisbury Road. The home of John Wigham, Jr, cousin of the John Wigham who lived at 5 South Gray Street. Douglass stayed here at the end of October, penning his response to charges against him made by the American Presbyterian Samuel Cox, revealing his ‘pretensions to abolition as brazen hypocrisy or self-deception.’ |

|

5 South Gray Street. Douglass probably visited the home of John Wigham, of the Edinburgh Emancipation Society. His wife Jane and daughter Eliza, both active in the – more radical – Edinburgh Ladies’ Emancipation Society, were among Douglass’ most loyal supporters in the city. |

|

7 Montpelier. Home of Mary Welsh, an abolitionist who continued to be active in the Glasgow Women’s Anti-Slavery Society, after moving to Edinburgh. Douglass may have visited, as Welsh was in the same social circle as the Wighams. A detached house with generous grounds at the time, the site is now occupied by tenements next to Bruntsfield Primary School. |

|

Broughton Place Church (Not on map). Venue for the United Associate Synod, which Douglass attended on 8 May for its debate on slavery. Although it passed a motion that met his approval, he was not permitted to voice his thanks. The building has been restored and is currently occupied by an upmarket auction house. |

|

Tanfield Hall, Canonmills (Not on map). Venue for the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland, which Douglass and his fellow abolitionists attended on 30 May. Situated at the foot of Dundas Street, beside the Water of Leith, it was used as a meeting hall from 1839. The site was redeveloped as a modern office building in 1991. |

For the full text of newspaper reports of Douglass’ 1846 speeches in Edinburgh (and elsewhere in Scotland) see this list of his speaking engagements.

One comment on “Spotlight: Edinburgh”

I love being here and following your wonderful map, walking in Douglass’s footsteps. Thank you. Alasdair for all your work.