Glasgow has a distinguished tradition of creating alternative forums of dissent whenever the civic authorities announce their latest orgy of self-congratulation. Especially perhaps when it concerns the city’s relationship to the wider world.

When Glasgow hosted the Commonwealth Games in 2014, Louise Welsh and Jude Barber convened The Empire Cafe in the Briggait as a space for readings, discussions, performances, exhibitions and refreshments that interrogated Scotland’s relationship to Atlantic slavery. This being one of the vectors of Empire the term ‘Commonwealth’ often obscures.

And amid the frenzy of cultural gentrification planned by the District Council when Glasgow was named European City of Culture 1990, a group of activists under the banner Workers City drew attention to cultures and histories the programme chose to overlook. Regarding the ‘Merchant City’ brand, one article in the Glasgow Keelie pronounced it

nothing short of disgraceful. Surely the Labour Councillors are aware that these ‘merchants’ made their colossal fortunes on the backs of thousands of slaves forced to work on tobacco, cotton and sugar plantations? The names of Glassford, Finlay and Colquhoun appear in most archives held in American Museums and Universities devoted to the history of slavery in the western hemisphere. How can the labour movement even associate itself with such people, let alone glorify them, in the way the District Labour Council does?1

Bellahouston for the Day

And before all that was 1938. That year Glasgow hosted the Empire Exhibition in Bellahouston Park, opened by the King in May, a few weeks after Hitler marched into Austria. It attracted over 12 million visitors over the next six months, despite the wet summer. The site included a number of temporary pavilions (showcasing Industry, Engineering and the produce of ‘the various Dominions and Colonies’), a ‘Highland village’, and two structures intended to be permanent: the Palace of Art (which still stands) and the 300-feet-high Tait Tower (which was dismantled the following year).

There were cafes and restaurants, and a young Canadian Billy Butlin was awarded the contract to run an amusement park. There was a football tournament, film screenings and a wide range of musical performances from leading orchestras, choirs and dance bands, with featured artists including Fritz Kreisler, Gracie Fields and Paul Robeson, as well as celebrity appearances by the Aga Khan and the visiting Australian cricket team.2

Reporting on the Royal Visit the Glasgow Herald remarked

Time was when the Socialist town councillor was apt to be cynical over demonstrations of loyalty at royal visits, but that attitude has completely gone with the change in political fortune that has invested the party with more public responsibility.

And it looked forward to ‘the Socialist section of the Corporation’ gladly joining in the ‘demonstrative welcome of the King and Queen.’ However, it did admit that there was likely to be resistance from ‘the small I.L.P. Group.’3

Dissenting Voices

The Independent Labour Party had withdrawn its affiliation from the Labour Party in 1932, and its influence had much declined. But it remained a potent force in Glasgow, where the party still had more MPs than Labour (including James Maxton) and could still boast over a dozen councillors, with representation strong in certain areas, notably Shettleston and Bridgeton.4 If its power to influence Council policy was weak, the party’s ability to organise meetings and demonstrations remained undiminished.

During the 1930s Black radical intellectuals based in Britain such as C L R James, George Padmore and Jomo Kenyatta pushed the ILP to challenge working-class racism and engage extensively with imperial issues; it was also the only party on the left to openly criticise Stalin.5

Dominant themes in its newspaper the New Leader during 1938 were the Spanish Civil War; the collapse of the Popular Front in France; the inactivity of the League of Nations in the face of the invasions of Abyssinia, China and Spain; and workers’ demonstrations and strikes in the West Indies, especially Jamaica. The holding of the Empire Exhibition in Glasgow provided a good excuse to intensify its anti-imperialist polemic, which flavoured the May Day demonstrations that year, supported by an eight-page Empire Special supplement.6 The paper also planned a series of articles entitled ‘Behind the Empire Exhibition’, of which, however, only one appeared, ‘Police Fire on Jamaica Strikers’.7

The Empire Exhibition Racket

Even before the exhibition opened, Councillor W R Gault, who contributed regular reports on the activity of the ILP in Glasgow, was decrying the ‘Empire Exhibition racket’, in particular the ‘vandalism of the Exhibition authorities which threatens to destroy for all time the amenities of Bellahouston Park’.8

A month later his outrage had gathered steam: ‘The state of mind some of our Labour Councillors have reached in their desire to exalt Imperialism, Nationalism, Militarism, and Royalty is almost unbelievable. Not for many years has everything that Toryism symbolises had such feverish propaganda’.9

In August the New Leader pointed out that attendants in the Amusement Park were compelled to work a 68-hour week and charged the same price for meals as the visitors. Letters to the press on the subject were not published and the Council claimed they had no jurisdiction.10

But the ILP’s main objection to the Exhibition was that it peddled ‘illusions about justice and democracy in the British Empire’ in order ‘to encourage national unity and patriotism in Britain’.11

These are the words of Arthur Ballard, one of the Exhibition’s most vocal critics. A carpenter from Croydon, he was remembered by his close friend C L R James as ‘a very tall, handsome, striking looking man who was working as a proletarian in industry, but who was destined to be an intellectual.’12

Ballard went on to elaborate at greater length:

If you want to see the Empire as it really is you won’t visit the Empire Exhibition in Glasgow. The organisers have spared nothing to put on a good show and the Exhibition itself is a monument to their work. Walking amidst the wonderful buildings, which are a rainbow of colour, surrounded by gardens and cascades of water, one thinks that the Empire is just a paradise on earth.

We are told that one of the objects of the Exhibition is ’to emphasise to the world the peaceful aspirations of the British Commonwealth.’ The average visitor, amidst this setting, may be carried away by this propaganda unless we are able to do something to present the real situation within the Empire.

Even in the ‘Peace Pavillion’ we get nothing but glorification of the League of Nations. Amongst the ‘pioneers of peace’ we find Tsars and Popes, we learn that slavery has been ‘abolished’ in China and that Italy has abolished ‘slavery’ in Abyssinia in 1936. Possibly the organisers anticipated some visitors with a Socialist tinge, so we get the slogan ‘Peoples of the World Unite’ with a quotation of Burns thrown in!

The ‘brightest jewel in the British Crown’ – India – is conspicuous by its absence, while the TUC pavilion is devoted entirely to Trade Union organisation in Britain! While it does not attempt to put over Imperialist propaganda, it is regrettable that the TUC does not say anything about the deplorable conditions within the Empire itself.

In the West African Pavillion we find furniture which is suited to grace the apartment of any Park Lane parasite; but naturally there is no mention of the horrible conditions in Africa itself. This is general of the whole of the Exhibition. All the resources of Capitalism have been used to glorify an Empire under whose flag conditions are equal to those within the Fascist countries.

The Revolutionary Socialists in Glasgow will have a difficult job in their attempt to present the opposite picture. How can this be done?13

An Anti-Empire Exhibition

Ballard had a plan. They would run an ‘Anti-Empire Exhibition’. His article continued:

The ILP in collaboration with various colonial workers’ organisations and individuals are preparing to conduct an intensive anti-Imperialist campaign in Glasgow during the month of August, when most people will be visiting the Exhibition

We propose, with the limited means at our disposal, to organise an anti-Imperialist annexe which will present the other side.

While we cannot put on an elaborate show, we believe that we can, by means of our Exhibition, at least show to the workers the intolerable conditions within the Empire and the necessity of their support for the anti-Imperialist struggle.

We appeal to all readers of our paper to assist us in this effort. We want any material and particularly photographs that usefully illustrate the conditions of the colonial workers.14

The exhibition was held in Kingston Hall on Paisley Road on the bus route many would have taken on their way to Bellahouston Park. Opened by the novelist Ethel Mannin, it ran from 13-27 August on weekday evenings (and from 2.30pm on Saturdays). Devised by Arthur Ballard himself, the event also bore the stamp of George Padmore, who spoke at the May Day rally at City Halls in Glasgow on 1 May.15

The New Leader described the exhibition as follows:

The exhibits will be grouped around a central column, which will show that the real owners of the Empire are not the people of Britain or of the colonies, but the big financial and commercial interests centred in London.

Round the hall will be sections devoted to various parts of the Empire. Particularly striking are the sections dealing with the British West Indies, showing the intolerable conditions existing. The section devoted to the recent terror against the unemployed in Vancouver brings the Exhibition right up to date.

The Exhibition is in a blue and grey colour scheme – similar to Bellahouston. It has involved weeks of preparation, long research work, and the gathering of material from three continents. The Committee has had the help of a group of London artists, all working voluntarily.16

As far as I know there are no photographs of the exhibition itself, but we can get an idea of it from the brochure that was produced in conjunction with it.

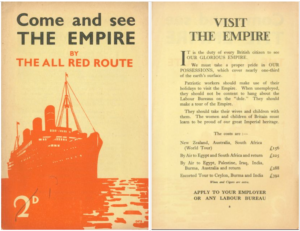

The All-Red Route

The title of Come and See the Empire by the All Red Route 17 appears to be an ironic nod to the ‘All-Red Route’, a miniature railway built for the 1911 Crystal Palace exhibition, linking the pavilions and outdoor panoramas.18 But here the ‘red’ (the colour long used on maps designating the extent of the British Empire) acquires a revolutionary connotation in a publication that announces its desire to ‘help end the tyranny of British Imperialism’.19

It adopts the style of a holiday brochure, offering various (priced) tours that will allow ‘every British citizen to see OUR GLORIOUS EMPIRE’ – including ‘patriotic workers’ who are recommended to ‘make use of their holidays’ or the free time they have when unemployed. ‘We must take a proper pride in OUR POSSESSIONS, which cover nearly one-third of the earth’s surface.’20

But the sarcasm soon gives way to a more earnest catalogue of injustices. After introducing readers to the ‘luxury liner’ they will be travelling on – ‘quite a comfortable little tub for the 250 guineas round trip’ – they are reminded that it ‘is not so comfortable for the British seamen and stewards and the 45,000 lascars (Indian sailors) employed by the various famous shipping companies … which cover our route.’21

And so at each port of call on the way – West Africa, South Africa, Kenya, India, Ceylon, Australia, Hong Kong, China, the Caribbean and Ireland. The celebratory rhetoric of the Empire Exhibition is replaced by a more damning assessment. Here is the official guide on the West African Pavilion:

The Gold Coast is the world’s largest producer of cocoa … In the second section [of the hall] the agricultural riches of the colony are displayed. Cocoa, one prized by the Aztec kings and now, in its many forms, a good and drink for all the world, is given pride of place and is shown in every stage of its preparation, from the ripened pod to luxury chocolate.22

And here is the ILP brochure:

Cocoa is one of the main products of this part of the world. The great cocoa and chocolate firms form a ring which has a stranglehold on the small farmers who grow the cocoa. Cocoa prices have been forced down to a point where they a ruinous to the growers. (But you haven’t noticed that the price of your tin of cocoa has dropped, have you?)

The same ring also owns the trading and transport industries – so the farmer has had to buy from, and sell to, the same people. Any attempt to break the ring is countered with all the great resources of these capitalists.

Still, the growers are fighting hard, even to the length of going on strike and refusing to grow cocoa….23

The ILP counter-exhibition and brochure was not the only dissident voice in 1938. I understand that the anarchist Guy Aldred published a pamphlet entitled Boycott Bellahouston! What Empire Means to India and British West Indies, although I have not yet seen a copy. The title in this case echoing that of a flyer signed by André Breton and other French surrealists, ‘Ne visitez pas l’Exposition Coloniale’, protesting the Colonial Exhibition in Paris in 1931, an earlier imperial extravaganza that also prompted the creation of a counter-exhibition.24

A New Museum?

The counter-exhibition seems to have been funded largely through donations and the sale of programmes and pamphlets. In September, Gault’s column in the New Leader referred to the ILP’s struggle to secure a grant towards running the exhibition. In the end the council let them off half the rent of the hall.25

How much impact the ‘other Exhibition’ of 1938 had is hard to gauge. Half-way through its run, the New Leader pronounced it ‘a great success. The hall was packed and representative people from all sections of the Working-Class Movement were present’. It also claimed that ‘over five hundred programmes and two hundred pamphlets were sold at the door during the afternoon and evening, as well as a record sale of general anti-Imperialist literature’, which may be an exaggeration; certainly the claim that it ‘has received large scale notice in all the Scottish papers’ was.26

It is even harder to get a sense of what those involved learnt from it and how much the event smouldered in the collective memory of Glasgow’s radical traditions. But the provocative display in Kingston Hall did leave us the brochure, which can be taken up again today and be given a new life.

In the last few years, there have been increasing calls, led by the Coalition for Racial Equality and Rights (CRER), for the creation of a museum of slavery or empire in Scotland. Last year Glasgow Life announced that it ‘will appoint a curator who will develop a strategy for the interpretation of slavery and empire in Glasgow Museums’ as a first step. And the calls were echoed by MSPs of all parties in the Scottish Parliament in June this year.

Already a Scottish Empire Museum has appeared online, describing itself as a ‘digital space’ that aims to promote ‘a better understanding … of the history of empire, colonialism, slavery and migration so we learn can learn from the past to understand the present and agitate for change in the world we want to live in in the future.’ If a physical museum does come to pass in Glasgow – the strongest contender for its location at the time of writing seems to be the Egyptian Halls on Union Street – perhaps the local authority will contribute more than a miserly rent rebate. And, as well as ‘telling the truth’ about colonial slavery and imperial rule, let’s hope it will pay homage to the long history of dissent at home that has been struggling to tell this story for decades.

Perhaps imaginative interventions like the ‘All Red Route’ can be reignited and allowed to throw a spark across the years and be r recruited to effectively teach us about Empire today. What would an early 21st-century version of the brochure – and by extension the exhibition – look like?

Notes

This is a work in progress, part of a larger research project on critical responses to the 1938 Empire Exhibition, currently stalled by the closure of libraries and archives due to the COVID-19 crisis.

- ‘A Bygone Radical History of the TUC’ Glasgow Keelie (September 1991).

- For an overview see Bob Crampsey, The Empire Exhibition of 1938: The Last Durbar (Edinburgh: Mainstream, 1988).

- Glasgow Herald, 3 May 1938.

- Gidon Cohen, ‘The Independent Labour Party 1932-1939’, PhD thesis, University of York (2000), pp. 58-67.

- Priyamvada Gopal, Insurgent Empire: Anticolonial Resistance and British Dissent (London: Verso, 2019), pp. 371-72.

- New Leader, 29 April 1938.

- New Leader, 6 May 1938.

- William Gault, ‘Glasgow Labour Party Play the Tory Game’, New Leader, 22 April 1938.

- W R Gault, ‘Red Glasgow’s Empire Exhibition’, New Leader, 6 May 1938.

- W L Taylor, ‘Shocking Conditions at Empire Exhibition’, New Leader, 9 August 1938. While nothing was done to improve their conditions, the drivers and conductors of the autotrucks which ferried people around the Exhibition grounds went on strike and succeeded in getting a pay rise. See Crampsey, Empire Exhibition, p. 108.

- Arthur Ballard, ‘White Justice and Black’, New Leader, 20 May 1938.

- Interview with C L R James by Al Richardson, Clarence Chrysostom and Anna Grimshaw, November 1986.

- Arthur Ballard, ‘We Are Going to Run An Anti-Empire Exhibition’, New Leader, 3 June 1938.

- Ibid.

- The best account of this anti-empire exhibition is in Sarah Britton, ‘”Come and See the Empire by the All Red Route!”: Anti-Imperialism and Exhibitions in Interwar Britain’, History Workshop Journal 69 (Spring 2010), pp. 68-89.

- The “Other” Exhibition’, New Leader, 12 August 1938.

- Come and See the Empire by the All Red Route (Np: Workers’ Empire Exhibition Committee, 1938).

- John M MacKenzie, Propaganda and Empire: The Manipulation of British Public Opinion, 1880-1960 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984), pp. 106-7.

- Come and See the Empire, p 16.

- Ibid., p2.

- Ibid., p3

- Empire Exhibition: Official Guide (Glasgow: 1938), pp. 154-55.

- Come and See the Empire, p. 4.

- André Breton et al, ‘Ne visitez pas l’Exposition Coloniale’. For further background (especially on the ‘counter-exhibition, ‘La Vérité sur les Colonies’) see Jody Blake, ‘The Truth about the Colonies, 1931: Art Indigene in Service of the Revolution’, Oxford Art Journal, Vol 25 No 1 (2002), pp. 37-58.

- New Leader, 23 September 1938.

- ‘Success of Anti-Imperialist Exhibition’, New Leader, 19 August 1938.