There is no record of his contribution, however. Nevertheless the meeting is of great significance, because it was the first time that secret negotiations over the purchase of Douglass’ freedom were made public.

Over the summer, Douglass had spent some time in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, a guest of Anna Richardson and her husband Henry. They were abolitionists more sympathetic to (but not uncritical of) the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society than the Garrisonians. Many years later, another visiting American – the civil rights campaigner Ida B. Wells – invited Anna’s sister-in-law Ellen to recall the occasion:

She said that Mr. Douglass, her brother and herself were at the seaside; that while sitting on the sand listening to the fugitive slave’s talk, and observing his sadness, she suddenly asked him, ‘Frederick, would you like to go back to America?’ Of course his reply was in the affirmative and like a flash the inspiration came to her. ‘Why not buy his freedom?’1

She didn’t tell Douglass at first, suspecting that he would not agree to it on principle, but, discreetly, Ellen Richardson wrote letter to ‘different influential persons’ in Britain asking for support. A contribution of £50 from John Bright, the Radical MP for Durham, encouraged her, and only then did she confide to Anna. Communicating through lawyers in Boston and Baltimore, they persuaded Hugh Auld (ownership having passed from his brother Thomas) to agree to a price of £150. The formalities were completed in December and Douglass was now a free man.2

Very few people knew about the plan. Those involved were presumably sworn to secrecy. We do not know when the sisters told Douglass what they were up to, and he may well have read the signs before they did so. But in Edinburgh at the end of October, the news was out.

The reactions of some of Douglass’s supporters were muted, to say the least. In Glasgow, Catherine Paton wrote, ‘I could not aid nor approve of the buying of Frederick, as I thought it compromising of principle, & a recognition of the right of property in man; I could not see how Garrison could approve it.’4 The same day, Mary Welsh of the Glasgow Female Anti-Slavery Society told Maria Weston Chapman in Boston: ‘Some of us have been very much grieved at Anna Richardson getting that money to purchase Frederick Douglass’s ransome.’4

The most forthright response came from Douglass’ fellow campaigner Henry Clarke Wright, who addressed Douglass directly. ‘This is the first letter of advice I ever wrote to you –, ‘ he began. ‘It is the last.’5 Douglass wrote back a considered reply, confirming that he was not only happy that the transaction had been effected, but happy to publicly acknowledge it.6 And when Garrison published the exchange between them in the Liberator, he remarked: ‘We think the reply of Mr. Douglass is not only entirely satisfactory and conclusive, but remarkably pertinent and forcible.’7 Thus Garrison – present at the meeting where plans for the purchase was first announced to the world – defied the Garrisonians. He admitted that the sale breached a general principle – he would never have countenanced negotiating the purchase of the entire slave population (as the British government had effectively done in 1834) – but insisted it was ‘expedient’ and ‘sound policy’ to do so in individual cases. ‘Human liberty,’ he declares, ‘is of incomparably greater value than money.’8

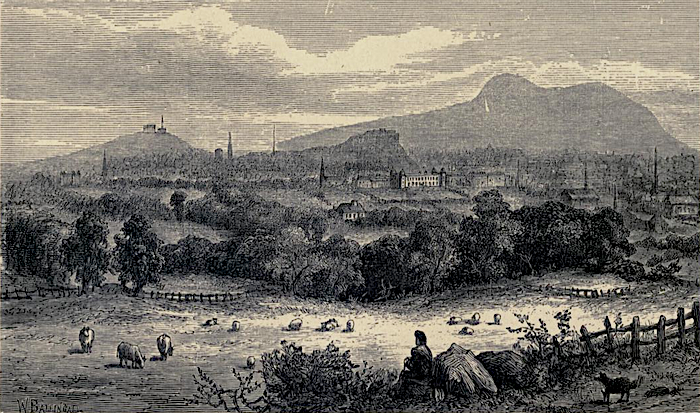

For an overview of Douglass’s activities in Edinburgh during the year, see Spotlight: Edinburgh.

ANTI-SLAVERY MEETING.

ANOTHER meeting was held on Thursday night in the Music Hall, for the purpose of hearing addresses by the representatives of the American Abolitionists on slavery in general, and on the proceeding of the Free Church and the Evangelical Alliance in regard to the Transatlantic pro-slavery Churches.

The CHAIRMAN announced that the master of Frederick Douglas, in the United States, had offered to give up all claim to him for £150. A lady in Newcastle had raised for this purpose £70, and had written to the friends of the abolition cause in Edinburgh, urging them to make exertions to complete the sum required, so that Douglas might obtain entire freedom. The Chairman therefore recommended that subscriptions should be raised in this city to accomplish this object, and stated that already several pounds had been obtained.

Mr GARRISON then addressed the meeting. He said that he seconded with all his heart the ransom of Frederick Douglas in America. He had always repudiated the doctrine of compensation to slave-holders, as he held them to be man-stealers. Those who contended for compensation, in his opinion recognised the right of slaveholders to keep their fellow-men in bondage; but while he did not recognise this right, he was anxious that Frederick Douglas should be ransomed, that he might return to his native land. Frederick Douglas had lived several years out of bondage in Massachusetts, in sight of Bunker’s Hill, and yet they had to ask the people of Edinburgh to contribute money that he might not be sent back to chains. Mr Garrison then at great length vindicated himself and Mr H.C. Wright from the attacks that had been made upon them on the score of infidelity, in the Witness, the Northern Warder, the Liverpool Courier, &c. He concluded by stating that this was the last meeting which he was likely to address in Scotland. The reception which he had met with throughout Scotland was as gratifying as his heart could desire, and was a thousand times more than he could have anticipated in the circumstances.

Mr MACARA, W.S., here rose, and proceeded to argue at considerable length that the Bible authorised slavery, and in support of this opinion he quoted such passages as Lev. xxv. 4 and 1 Cor. vii. 2.

When Mr Macara had spoken about half an hour, a Mr Gilchrist came forward and addressed the meeting, denouncing the conduct of Mr Thompson and his coadjutors in stirring up religious strife and animosity in the country by their virulent attacks on certain sections of the Christian Church, and particularly in their crusade against the Evangelical Alliance. He said that slavery was entirely a political question, and one with which the Alliance, as a religious body, had nothing to do, and that it was the province of the Congress of the United States to take up and dispose of that subject, as it alone possessed the power to abolish slavery in that country.

Mr GEORGE THOMPSON replied at considerable length, and showed that slavery was not a political, but a moral and religious question. He contended that, as all kinds of theft were immoral, the crime of man-stealing was a sin of the most aggravated kind, and that it became ministers of religion to exclude from their communion all persons who participated in it; and therefore, as the American deputation to the Alliance were aiders and abettors of slavery, they ought to have been excluded from its fellowship. After stating, in answer to Mr Gilchrist, that the Congress of the United States could not abolish slavery, as each state possessed that power within itself, Mr Thompson defended the conduct of himself and his coadjutors for arraigning the procedure of the Evangelical Alliance, which he said would certainly come to nought, unless they acted more in accordance with the religion of Jesus Christ, by renouncing all connection with slave-holders.

Scotsman, 31 October 1846

ANTI-SLAVERY MEETING. – Another meeting was held on Thursday night in the Music Hall, for the purposes of hearing addresses by the representatives of the American Abolitionists on slavery in general, and on the proceeding of the Free Church and the Evangelical Alliance in regard to the Transatlantic pro-slavery Churches. Mr Wigham presided over the vast assemblage, supported by a large number of gentlemen on the platform. Mr Lloyd Garrison and Mr George Thompson were the chief speakers. Two persons, one of them a student, stood up and defended the Free Church and the Evangelical Alliance at considerable length. Their arguments, however, were replied to by Mr Thompson, who also with his accustomed ability and happy tact, succeeded in keeping the audience in great merriment at the expense of the student. The proceedings did not terminate till twelve o’clock, having occupied about five hours, during which the attention and interest of the audience did not seem for a single moment to flag.

Edinburgh Evening Post, 31 October 1846; Caledonian Mercury, 2 November 1846

Notes

- Ida B. Wells, ‘Newcastle Notes’ (1894) in Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells, ed. Alfreda M. Duster (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970), p 162.

- See William McFeely, Frederick Douglass (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1991), pp 137–8, 143–4; Leigh Fought, Women in the World of Frederick Douglass (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 90–1.

- Catherine Paton to unidentified recipient, Glasgow, 17 November 1846 in British and American Abolitionists: An Episode in Transatlantic Understanding, edited by Clare Taylor (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1974), p. 299.

- Mary Welsh to Maria Weston Chapman, Edinburgh, 17 November 1846, in British and American Abolitionists, p. 300.

- Henry Clarke Wright to Frederick Douglass, Doncaster, 12 December 1846, in The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series Three: Correspondence, Volume 1: 1842–52, edited by John R. McKivigan (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), p. 179.

- Frederick Douglass to Henry Clarke Wright, Manchester, 22 December 1846, in The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series Three: Correspondence, Volume 1, pp. 183–9. The following day Wright and Douglass shared a platform in Leeds. Douglass repeated his defence of the sale in a letter to the Durham Chronicle, which was widely reprinted in the British press: Douglass to editor, Coventry, 22 January 1847, in The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series Three: Correspondence, Volume 1, pp. 196–200.

- William Lloyd Garrison, ‘The Ransom,’ Liberator, 29 January 1847.

- William Lloyd Garrison, ‘The Ransom of Douglass,’ Liberator, 5 March 1847.

![Notice of Anti-Slavery Meeting in Edinburgh's Music Hall, 29 Oct 1846 featuring William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglas[s] and George Thompson](https://www.bulldozia.com/wp-content/uploads/1846-10-28_Scotsman_noticeMusicHall29Oct.png)