They held a meeting in the new City Hall on Friday 23 January. Opened only the previous year, it would host public meetings, exhibitions, lectures, soirees, bazaars, and musical and theatrical performances for half a century. Perhaps its most famous attraction was the Swedish soprano, Jenny Lind, who sang there in 1847.

‘Three thousand crowded in,’ wrote Wright, ‘and as many more came and had to go away. So densely crowded that we had to break up the meeting before the time, for fear of accidents.’3

Another meeting at the same venue on Monday 26 January was

admission by tickets, four cents each. Thirteen hundred tickets were sold during the day. About 1500 persons present from 7 to 11 – so intensely interested are they. If Frederick gives himself to anti-Slavery in Scotland, three or four months, he and J. N. Buffum could do more for our cause in America than they could do in a year in any other part of the kingdom.4

Wright reports that ‘four anti-slavery meetings we have held here.’5 Douglass refers to ‘five meetings in Perth’.6 The dates and locations of the other meetings are not known. Perhaps one or two were held on Saturday 24 January, but they could also have lectured earlier in the week. Douglass had been in town since at least Tuesday 20 January.7 The newspaper reports reproduced below do not shed any further light on these other meetings, nor do they give a detailed account of the content of Douglass’ speeches, but they do convey something of his reception in Perth. Here, for the first time, he condemns the Free Church of Scotland for its refusal to break ties with Presbyterian churches in the United States. This would be the theme of many of his subsequent speeches, which called on it to return the donations solicited by a Free Church delegation which visited in early 1844.

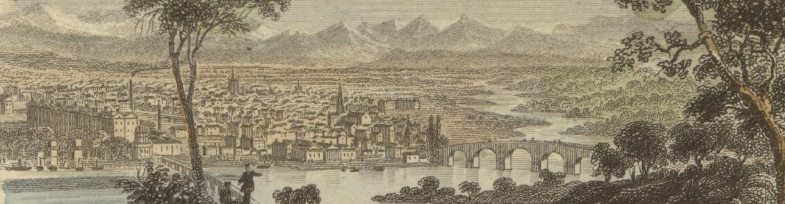

The morning after the Monday meeting, Douglass himself wrote to Garrison. But rather than duplicate the account of his fellow-campaigner, he used most of his letter to respond to something he had read in a recent issue of the Liberator, which he would probably have perused in Glasgow. He was incensed by the allegations made by a certain A. C. C. Thompson in the Delaware Republican, questioning the veracity of his newly-published Narrative. Thompson refused to believe that its author was the same person as the young man he had known in Maryland. In his rebuttal, Douglass made much of the contrast between how he was then and how he was now, exploiting the historical associations of his present surroundings on the very edge of the Scottish Highlands.

I fancy you would scarcely know me. I think I have altered very much in my general appearance, and know that I have in my manners. You remember when I used to meet you on the road to St Michaels, or near Mr Covey’s lane gate, I hardly dared to lift my head, and look up at you. If I should meet you now, amid the free hills of old Scotland, where the ancient ‘black Douglass’ once met his foes, I presume I might summon sufficient fortitude to look you full in the face; and were you to attempt to make a slave of me, it is possible you might find me almost as disagreeable a subject, as was the Douglass to whom I have just referred. Of one thing, I am certain – you would see a great change in me!’8

Later that day Douglass and Buffum took the coach to Dundee, a ride of some three hours along the north banks of the Tay. The railway, still under construction, would halve the journey time when it opened in 1848.

UNITED-STATES SLAVERY.– Numerous and respectable audiences have been repeatedly addressed here, within the last ten days, by a deputation from North America, consisting of Frederick Douglass, a self-emancipated slave; Messrs. Buffum and Henry C. Wright, also from the States of the Union, – with a view to awaken the sympathies of our countrymen for the degraded and abject condition of about three millions of human beings in the Southern States of America, suffering evils harder to be borne than even the negroes of our West-Indian plantations were ever subjected to. The slave Douglass is a noble instance of what the power of the mind may achieve under all the means that may be taken to debase and enslave it. He is a man of brilliant intellect, highly gifted even as an orator, and a most able advocate for the unfortunate race of our fellow-creatures whom he represents. Mr. Wright is also a powerful and argumentative reasoner, and never allows the attention of his audience to flag for a single instant. The picture they draw of negro slavery in the States – and we believe it is a just one – is absolutely sickening to any philanthropic heart. The slavery of the mind, in that abominable system, is even more deplorable than the enthralment of the body, and is more disgraceful to those who practise it than those who endure it. On Friday and Monday last, these strangers found it necessary, for sufficient accommodation, to occupy the City Hall, which was completely filled on both occasions. Both the orators we have alluded to administered the most withering castigation on the Free Church for its recognising Christian fellowship with the slaveholders, for the sake of their money.

Perthshire Constitutional, 28 January 1846 (repr. Liberator, 27 February 1846).

AMERICAN SLAVERY. – Several addresses have been delivered in the City-Hall, and other places, here, within the last eight days, on the subject of slavery in America, by Mr. F. Douglass (a coloured person, described as a fugitive slave from the States), by Mr. Henry C. Wright of Philadelphia, and Mr. Buffum of New York.9 All of these gentlemen are tolerable speakers, and were listened to with much interest by large and respectable audiences. Mr. Douglass, particularly, is no mean adept in popular oratory. He declaims with considerable vigour, and is not deficient either in pathos or sarcasm. There was, of course, nothing very novel in the statements or information given by these gentlemen, and therefore we do not consider it necesary to present any report, as our readers have abundant knowledge regarding the slave system of America, and its various horrible consequences. All the speakers dealt out severe condemnation to the Free Church of this country for so far fraternizing with the slaveholders of the Union as to receive their contributions. These animadversions occasionally provoked very opposite manifestations of sentiment among the audiences; but, on the whole, the majority seemed to concur in the justice of the censures. An interesting notice of Mr. Douglass will be found in Chambers’ Edinburgh Journal of last week.10

Perthshire Advertiser, 29 January, 1846

AMERICAN SLAVERY. – Several lectures have, during the last two days, been delivered in the City Hall and other meeting-houses, on the subject of American Slavery, by a Mr Frederick Douglass, a fugitive slave from the Southern States of America. The novelty of a slave addressing the people of this country could not fail to attract attention, and Mr Douglass had crowded audiences on every occasion on which he lectured. He, however, communicated nothing new on the slave system generally. He dealt heavy blows against every sect, party and denomination – Unitarians, Baptists, Methodists, Roman Catholics, &c. – in America, who all more or less gave countenance to the traffic in human bodies. He did not spare the Free Church of this country, and seemed to consider it the most prominent in the encouragement of the system, by its acceptance of money from the slave-holders in America, and called upon them to ‘send it back,’ and, if not to the original owners, for the purpose of establishing schools in the United States, wherein to educate fugitive slaves. There is a good deal to attract and interest in the narrations Mr Douglass gives of his own life while under bondage. – The manner in which he managed to acquire a knowledge of reading and writing, under the greatest difficulties, and at the risk of his life – his sufferings – his escape from bondage, and his emotions consequent thereon, when he felt he was free – all tend to produce and keep up no common interest. Besides, Mr Douglass has also the advantage of possessing mental attainments much beyond what might be generally supposed to belong to a slave; and can, thereby, be listened to, more than once, with interest. Indeed, we have had agitators of every school belonging to our own country in this city, many of whom cut a much poorer figure than this fugitive slave, in oratorial qualifications and mental display. On all the occasions of Mr Douglass’s lectures, although the houses were densely crowded, and himself considered at times rather severe in his strictures on the conduct of the leaders of the Free Church body, the great bulk of which formed his auditories, he was listened to throughout invariably with the most marked attention, and without the least symptoms of opposition.

Perthshire Courier, 29 January 1846

Notes

- A weather report in the Perthshire Courier on 29 January 1846 notes that the ‘unprecedentedly open and mild weather which has characterised the present month still continues’, with decidedly Spring-like temperatures of around 40–45 degrees Farenheit.

- Henry Clarke Wright to William Lloyd Garrison, Perth, 26 January 1846 (Liberator, 27 February 1846).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Frederick Douglass to James Standfield, Dundee, [29 January 1846] (Belfast Commercial Chronicle, 4 February 1846).

- A letter from Douglass to Richard Webb is dated ‘Perth, 20 January 1846’, The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series Three: Correspondence, Volume 1: 1842–52, edited by John R. McKivigan (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), pp. 80–1.

- Frederick Douglass to Wiliam Lloyd Garrison, Perth, 27 January 1846 (Liberator, 27 February 1846, reprinted inThe Frederick Douglass Papers, Series Three: Correspondence, Volume 1: 1842–52, edited by John R. McKivigan (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), p. 85). When Douglass chose to include this refutation of Thompson in an appendix to the second Dublin edition of his Narrative, which came out in the Spring, he revised it. This passage became: ‘The change wrought in me is truly amazing. If you should meet me now, you would scarcely know me. You know when I used to meet you near Covey’s wood-gate, I hardly dared to look up at you. If I should meet you where I now am, amid the free hills of Old Scotland, where the ancient “Black Douglass” once met his foes, I presume I might summon sufficient fortitude to look you full in the face. It may be that, wearing the brave name which I have assumed, might lead me to deeds which would render our meeting not the most agreeable. Especially might this be the case, if you should attempt to enslave me. You would see a wonderful difference in me. I have really got out of my place; that is, I have got out of slavery, which you know is “the place” for negroes in Christian America.’ Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself, 2nd Irish edition (Dublin: Chapman and Webb, 1846), p. cxxvii. I discuss this passage in more detail in my ‘From “the Black O’Connell” to “the Black Douglas”.’ New North Star: A Journal of the Life and Times of Frederick Douglass 3 (2021): 1-12 (8-12).

- The reporter was somewhat confused over the provenance of the speakers. Wright was not ‘of Philadelphia’ (he grew up in upstate New York and later moved to Massachusetts) and Buffum was not ‘of New York’ (he grew up in Maine, and later moved to Massachusetts).

- ‘Narrative of Frederick Douglass,’ Chambers’ Edinburgh Journal, 24 January 1846, pp. 56–59.

Last updated 23 January 2025