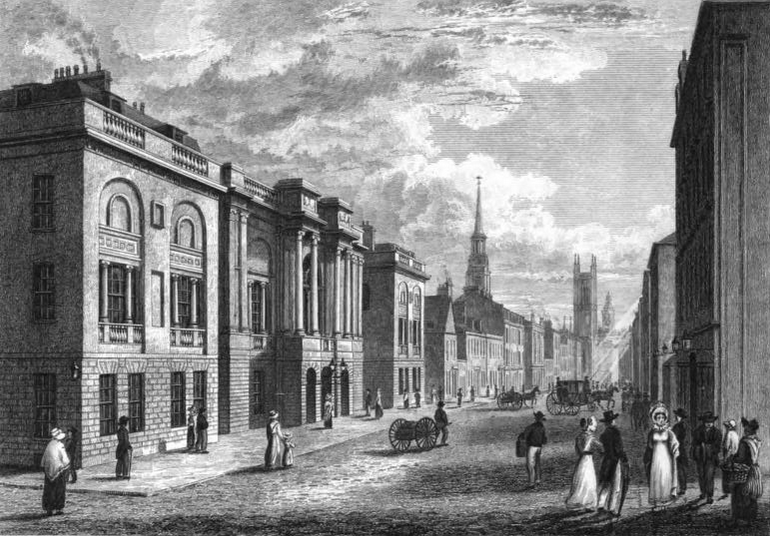

Following their lectures in Dundee and Arbroath the previous week, Frederick Douglass and James N. Buffum returned to Glasgow, probably on Monday 16 February. Buffum and Henry Clarke Wright addressed a Glasgow Anti-War Society meeting at City Hall on the Tuesday evening. In the report in the Glasgow Argus, there is no sign of Douglass’ participation.1 But he was advertised to ‘DELIVER an ADDRESS to the LADIES … on the Subject of SLAVERY in AMERICA’ at the Assembly Rooms (pictured above) the following afternoon.2 This was presumably organised by the Glasgow Female Anti-Slavery Society. No report of this meeting appears to have survived.

That evening – Wednesday 18 February (‘doors open at 6 o’clock, tea on table at 7’3) – Douglass and Buffum spoke at a packed meeting of the Scottish Temperance League at City Hall. The League was a relatively new organisation, formed in 1844, reaffirming (as the speeches suggest) a commitment to total abstinence rather than mere moderation. Among the other speakers were its president, Rev. William Reid (who also edited its journal, the Scottish Temperance Review), Robert Reid (secretary of its short-lived predecessor the Scottish Temperance Union), and two of its hired lecturers, Henry Vincent and Thomas Beggs.4 Vincent and Beggs were also associated with the Chartist movement.5 Later in the year, Douglass and Vincent would be involved in the formation, in London, of the Anti-Slavery League.

Contrary to the order of speeches in the Glasgow Examiner report, Robert Reid probably spoke before Beggs, judging by the content of his remarks. The evening, therefore, most likely followed the sequence recorded in the Glasgow Saturday Post. Both are reproduced in full below, followed by the much briefer account in the Glasgow Herald.

For an overview of Frederick Douglass’ activities in Glasgow during the year see: Spotlight: Glasgow.

SCOTTISH TEMPERANCE LEAGUE

On Wednesday evening, a tea party was held in the City Hall, under the auspices of the Scottish Temperance League. The area of the hall was nearly filled by a most respectable company, nearly one-half of whom were ladies. We understand that a party from Paisley engaged a special railway train for their own accommodation, on this occasion. The Rev. Dr Bates occupied the chair, and amongst those on the platform were – The Rev. Wm. Reid, of Edinburgh, the Rev. Jas. Patterson, the Rev. Mr Nisbet, Rev. Mr Webb, Rev. P. Mearns, Dr Burns, Edinburgh, Dr Menzies, Edinburgh, Mr Turner, Thrushgrove, Mr Kettle, Mr H. Vincent, Mr R. Reid, Mr T. Beggs, Nottingham, Mr Meldrum, Paisley, Mr Waterson, Paisley, Dr Richmond, Paisley, Mr George Gaillie, Mr Crawford, Gorbals, Mr Winning, Paisley, Mr Dunn, Mr Smith, Mr Service, Mr A. Paton, Mr Govan, Mr Murray, Mr J. Keith, Mr Robert Rae, Mr W.S. Nichols, Mr E. Anderson, Mr Ronald Wright, Mr James Campbell, Mr Taylor, A. H. MacLean, &c. &c. Mrs Caldwell, of the Teetotal Tower, officiated at one of the tables.

A blessing having been asked by the Rev. Mr Patterson, the company was supplied with tea and its usual accompaniments. The Rev. Mr Reid returned thanks.

The CHAIRMAN then shortly addressed the meeting. He said he had been interested in the temperance reformation from its very beginning. He could well remember the remarks which the friends of the cause had been accustomed to hear respecting this movement at its commencement. The scheme had been looked upon as quite an outlandish thing, and some predicted that it would not last many months. More than twice seven years had elapsed since that time, however, and he would only refer to the present meeting for an answer to those gloomy predictions which they had been accustomed to hear.

Among the many objections made to the society, he would just mention one, namely, that it has been supposed to have an unfriendly aspect towards religion.

Now, it did seem to him passing strange how it could be supposed that sobriety and religion could have any repugnance or hostility to each other. If there have been advocates of the temperance cause unfriendly to religion, he had only to say that they have been grievously mistaken, because no reformation could be of any lasting utility which was not supported by religion. But it was marvellous that the friends of religion could have imagined that the temperance movement is unfavourable to religion and morality.

He believed that some things might have given a colour and a pretext to such imaginations by some parties. The advocates of the cause, not finding themselves supported by the Christian people generally, as they ought to be, may have indulged in a strain of censure and invective, which he was certain had done no good to the cause, and which they would not have employed had they soberly considered the effect likely to be produced.

Men of intelligence would not be dragged into any scheme. It is by forbearance, sound argument, and motives drawn from the true sources of true morality, that they would succeed in persuading Christian ministers to lend their aid to this cause. There were a considerable number of the ministers of the gospel who had already lent their aid to the movement, and he fondly cherished the hope that the number would speedily be increased. It was but fair, however, that they should have extended to them that forbearance which they themselves demanded, before they were fully convinced that this cause was well founded. (Applause.)

The Rev. Mr REID, of Edinburgh, congratulated the friends of the temperance movement on the peculiar happy circumstances in which they were assembled. He was sure that those who acted on the principle of abstinence were prepared to join with him in hearing testimony that the use of intoxicating liquors was not essential to health, social enjoyment, or domestic comfort, but that in each and all of these respects, they had been the better of their abstinence.

He felt unspeakable delight in the reflection, that during the last ten years not one of the ten thousand poor drivelling, cursing, soul ruined victims of intemperance who had passed into the eternal world, could point to him and say, ‘You, Sir, deceived me, you taught me that it was safe to drink;’ and in the conviction that he was innocent of all the evils which drinking had entailed upon the community, he experienced a gratification which he would not exchange for all the high-prized enjoyments of the drinking circle. Now, he would ask if it was rational to tolerate the continuance of a system which was inseparably associated with evils more dreadful, when a little denial of self-indulgence was adequate to its overthrow. We come to you then, he said, and ask you to unite with us in this most important movement.

Oh, one might say, it is not for all that I drink! Then just join. If the sacrifice be small, you lose little, and if the sacrifice be great, it is time for the sake of your personal safety.

But then says another – you teetotallers are such a low, vulgar race, that we would feel it degrading to be identified with you. Well, we are perhaps no better in this respect than we should be, but is all the vulgarity on our side? Are the ranks of moderationists so exceedingly silent? Perhaps a temperance soiree will bear comparison with a public dinner.

We admire your principle, says a third, but then we have a fear that you carry the thing too far, that you advocate it on unsafe ground. We have not yet got all our difficulties removed; and thus while you hesitate and delay, the drunkard perishes, and we seek to loose the yoke from his neck, and strike the galling fetters from his limbs.

But the programme requires me to speak of the spirit which becomes temperance reformers; and it is surely not too much to say in their behalf that it is true that they may gain for themselves a little notoriety, which higher causes deny them, not that they may find occupation for idle hours, or recreation from severer pursuits – not that they may have occasional gatherings with all the light-heartedness of holiday festivity, that they agitate the public mind on the question of temperance, but because homes are blighted, and churches disgraced, and the best prospects for time and eternity blasted – because they see a most insidious article advanced to the high position of being regarded as an emblem of all that is kind, given to children, and sanctioned by example the most powerful – because they see it vitiating the tastes, and demoralising the mind, and arresting the progress of social and intellectual improvement, that they step between the living and the dead, and lift their voices and spare not.

Mr Reid then went on to say that, in order to their bringing to the contest a force adequate to secure their object, it became them to estimate aright the system which they sought to overthrow. There, said he, is the power of the traffic. Every twentieth family is engaged in it. With their friends and dependents, all leagued to uphold it. There is the Government, under the mistaken idea of its promoting rational prosperity, affording every facility for the free circulation of the pernicious drug. There are the customs of society meeting us at every step of life, and sanctioning the system by all the influence of social kindness. And there, too, are the religious men of the present day, with few exceptions, standing aloof, and giving us the powerful opposition of moderate drinking and avowed neutrality. The force, then, said he, with which we have to contend is wide-spread and firmly planted.

Nothing, however, within the range of human possibility can withstand the power of indomitable perseverance.

The philanthropist may reserve his benevolence for other causes, but we shall yet seize on that principle which moves his pity for his fellow-men, and enlist him in our ranks.

The statesman, regardless of the interests of his country, may employ the article of adulteration as a means of increasing the national resources, but we shall yet teach him that it is one of the first principles of true political economy, that morality and industry are essential to a nation’s preservation and prosperity.

The church member may fold his arms in cold indifference, and shield himself from our appeals under the mistaken idea of Christian liberty and scriptural moderation, but we shall yet teach him that no man has liberty to follow courses dangerous to himself or others, and that the scriptures nowhere sanction the use of that which is pernicious in its tendency.

The minister of religion, too, offended that the taught should become his teacher, and enslaved by the customs of society, and the influence of those by whom he is surrounded, may withhold his countenance, and awaken in the bosoms of weak minded people the fear that our cause is neither Christian nor lawful, but the day shall yet come when his error will be discovered, and the fact appear that poor despised abstinence has in it more of the spirit of genuine Christianity than selfish, insidious, contemptible moderation.

The distiller and retailer may plead the sanction of religious men and the necessities of their families, but they shall yet learn that they are as certainly responsible for the tendency of their calling as for direct acts of transgression.

He asked the friends of the movement, then, to abide in its manifold relations to other causes, and in the spirit of faith and love to hasten forward to the glorious triumph which should yet assuredly reward the efforts and sacrifice to which they were now imperatively called.

Mr JAMES BUFFUM, of Massachusetts, spoke to the next sentiment – ‘The rise, progress, and results of the temperance movement in America.’

After a few preliminary remarks, Mr Buffum said – The temperance reformation in America commenced about the close of the revolutionary struggle which separated her from this country, and was first set a-going in consequence of the conduct of the soldiers, who had been provided largely with intoxicating liquor during that struggle, and who, having imbibed an appetite for drink, carried it, with all its evil consequences, into the heart of the community. To such an extent was the practice of intemperance carried at this time, that it was feared by many that they would become a nation of drunkards. Intemperance found its votaries in the church, in the congregation, in congress, on the judge’s bench, and among every class of society.

There was an anecdote which would show how far the demoralizing practice was carried among professing Christians. There was a church near to where he came from which had a member of the name of Brown, whose drinking habits were so notorious that the church met to consider his case. After deliberating, they appointed a committee to wait on him with the view of reproving him, and testing his fitness to continue in membership. Now, this committee was composed of moderate drinkers, and Mr Brown hearing of their coming prepared for their reception. He placed on a sideboard in the room which he intended to usher them into a quantity of wine, brandy, and other liquors, and after their arrival he said he hoped they would excuse him for a few minutes, as he had to go out on some necessary business. In the meantime (pointing to the sideboard), he desired them to make themselves at home. (Laughter.) Mr Brown stayed out of the way for nearly half an hour, and the committee, in his absence, did, indeed, make themselves quite at home with the liquor. (Laughter.) So much so, that when Mr Brown returned, they talked with him for about two hours on every subject but that which had taken them to his house, and they went away and reported to the church next week that Mr Brown had given them Christian satisfaction. (Laughter.)

About the same time when a church was building in Boston, and when the foundation stone was to be laid, a master-builder sent the operatives a barrel of New England rum. As a return for this very acceptable present, what did the operatives do? Why, they chiselled out of the letters of his name on the corner-stone. (Laughter.)

In the year 1826, however (the condition of the country in America being pretty much the same, in regard to intemperance, as he had seen since he had come here), the friends formed their own society, framed a constitution for it, and in only three years from that time there was a wonderful change in that community.

But notwithstanding, they had not then got the right principle to go upon. They went upon the principle that a man might drink if he only drank moderately, and on this acccount many who joined the Temperance Society were fast proceeding to intemperance. On this plan it was almost as difficult to say when a an drank moderately and when he drank intemperately, as when a pig was put into a sty to say when he became a hog. (Laughter.)

They came at last, however, to the proper principle – total abstinence – (cheers) – and under that principle their progress had not only been rapid, but secure and lasting. Mr Buffum made a few other appropriate remarks, and concluded amid loud cheering.

Mr BEGGS, of Nottingham, said it was a source of no ordinary gratification to a person who had laboured rather extensively in the temperance reformation for ten years past, to see so numerous and respectable a gathering assembled to hear testimony to the worth of their cause. He rejoiced in it, because it was an omen of a better time for the temperance movement than had hitherto presented itself in this country, and it would be seen by his observations, that he attached no ordinary importance to that movement.

The subject which he had to address them upon was, ‘The temperance reformation viewed as an agent of civilization;’ a subject which he felt to be a most important and interesting one. Every age of the world had called itself civilized, and rightly so, as compared with that which had immediately preceded it. Baron Dupin of France, who travelled through various countries in Europe, when he visited the metropolis of England, was taken to see those things which had hitherto constituted the boast of the people. He was shown all their great naval and military monuments to the men who had distinguished themselves in battle, and who had fell [sic] in their country’s cause on wave and field, and a considerable impression was made on his mind by this circumstance, and he said indignantly, that it was not by any of these things that they were able to distinguish a great nation, let them take him to the cottage homes of their people, and show him industry, piety, cleanliness, and comfort, and then they would be entitled to claim the first rank in the march of civilization.6 (Applause.)

This was brought to his recollection by the same sentiment being emanated to-night by a previous speaker; and there was nothing that he (Mr B.) was more convinced of than this, that they could expect nothing from England unless they began their reformation in the cottages and homes of the people; and he believed the foundation of all character, both social and national, was founded on the domestic affections, and emanated from their own firesides.

Mr B. went on to make some remarks in relation to their present state of civilization in this country, and in the course of his observations he addressed a number of interesting statistical details, showing the effect of the drinking customs upon the health and comfort of the people, both in the manufacturing and agricultural districts.

He then defended the teetotallers from the charge of going too far, and illustrated the danger of going any length in the use of intoxicating drinks. It was absolutely necessary, if they wished to effect the desired reformation that example should accompany precept, for they might preach and teach till they were tired, but all their preaching and teaching would do little good unless these were sustained by their own example.

After referring to a number of other topics in an elegant and impressive manner, he concluded his address amidst great applause.

Mr FREDERICK DOUGLASS, of Lynn, Massachusetts, next came forward to address the meeting, and was received with great applause. He felt proud, he said, to stand upon this platform. Others might regarded it as a privilege, but he felt he might justly be proud of the reception he had met with on standing forward here for the purpose of throwing in his mite towards advancing the cause of temperance in Scotland. He was thinking before he left his seat, of leaving to the eloquent gentleman who was to follow him, the time which he (Mr D.) was to occupy for he was certain that he would be able to say what was necessary to be said much better than he should be able to say it during the few minutes had had to speak to them.

The subject announced for him in the programme was the question of Intemperance, or the Drinking System viewed in connexion with Slavery. He confessed that he felt some difficulty in discussing the two subjects, the one in connection with the other. Still he had a few facts respecting the working of slavery in connection with intemperance in the United States, which, if he could throw any light on the subject, might be of importance at that time. They must remember that slavery was a poor school for rearing moralists or orators, and they would not expect much, therefore, from him on that score, for he was almost in as bad a predicament as his friend Buffum, who lost his green bag containing the notes of his address, because although he had brought his bag with him, there was nothing in it. He was afraid he would appear exceedingly green in the course of his speech. (Laughter, and great cheering.)

[Slaveholders Promoting Intoxicating Drink]

One of the principal means to which the slave-holder resorted, in subjecting the slave to his control, was to destroy the thinking powers of the slave, and then he might do what he pleased with his victim. This mode was resorted to by the slave-holder to destroy those characteristics which distinguished the slave from the brute creation, and this was the reason why they freely at times received intoxicating drink. On the Saturday nights, it was very common in the State of Maryland, where he was a slave, for the masters to give their slaves a considerable quantity of whisky to drink upon Sunday, to take from them the power of thinking and of devising their freedom. They cunningly and artfully gave them stupefying drink, and in this way succeeded in keeping far from them the means of emancipation. The slave-holders looked upon the slave, when he would not drink whisky, as a most ungrateful wretch, the allowance of his master being regarded as a boon; and those slaves who were looked upon as drunkards were at times encouraged to drink; and as they naturally suffered the penalty of their conduct, to the extent of their indulgence, this was done for the purpose of disgusting the slave with freedom.

The poor bondman was always desiring freedom, and there were certain days in the year when he might have liberty. The holidays were days of comparative liberty; instead, however, of making them days of pure and undefiled freedom, they made them days of disgusting vice and debauchery. Then when the slave had passed over his holiday, he felt that liberty after all was not of so much consequence, and that it was just as well to be enslaved by man as by whisky. He got up from his debauch, took a long breath, and went back to the arms of slavery without having advanced a single step in his way to freedom.

This was the effect of intoxicating drink which was as powerful in retarding the progress of liberty as of civilization. That nation, no matter how much it boasted of its freedom – no matter how free it might be from man – no matter how free it might be in its form of government, while its people drank deep of the intoxicating bowl they were slaves. (Applause.) It could not be otherwise. What was it that they desired to be free about man? It was the mind – the soul – the powers which distinguished him from the brute creation. It was this they desired to be free, but intemperance enslaved and paralyzed this; it bound stronger than iron, and made men the willing subjects of brutal control. (Cheers.)

The coloured population, he continued, of the United States have had great difficulties to contend with in rising from their degradation – difficulties unknown to the temperance cause in other lands. One of the great arguments of the enemies of the negroes has been his fondness of intoxicating drink, although he learnt this fondness from his master, he is denounced a drunkard – as worthless – as degraded – as being morally and religiously incapacitated to fill those stations in life equally with the white man – and in connection with this part of the subject I wish to state here some facts in regard to the progress of the coloured people in the United States, for I am informed that an individual has recently travelled to this country, who states in vindication of slavery, that between the negro and white man there is an impassable barrier, that the negroes are incapable of enjoying liberty with the white – and this argument is based on the degradation of the black.

Now, let me tell you what the free blacks of the northern States have had to contend with in becoming sober men. Instead of being encouraged and entreated by the philanthropists of that land to become temperate slaves and virtuous and industrious men, every possible hindrance has been thrown in their way, and by the power of the whites they have been kept back from moral and physical improvement.

[Abuse of Black Temperance Advocates]

In confirmation of this statement, I may mention one fact: I mean the case of a mob in 1842 in Philadelphia.

The black man, you must be aware, is excluded in that land of the free and the brave, from the temperance platform – but, thank God, I am not so here. (Loud and continued cheering.) You need not clap your hands, I was merely stating a fact. (Laughter and cheers.) You have merely clapped to no purpose. (Renewed laughter and cheers.) Why, I believe you have nearly clapped me out of my speech. (Loud and continued laughter.) I was proceeding to say then, that the coloured people being separated from the whites – seeing they were not allowed to come upon the temperance platform with the whites – and seeing at the same time that intemperance degraded the blacks as it did the whites – as temperance was beneficial to the one, so it would be to the other, resolved to have platforms of their own. (Cheers and laughter.)

Accordingly, Mr Robert Purves, a wealthy black, Mr Steven Smith, and a number of others, erected halls, employed lecturers to go among their coloured brethren to get them to sign the pledge, and in this way raised a large society.

The 1st of August, you know, is the anniversary of the emancipation of slaves in the West India islands and in 1842, on that day, the coloured people of Philadelphia felt disposed to make a demonstration on behalf of temperance, as well as to show their deep gratitude to God and to the philanthropists of this country, for striking the chains from the limbs of 800,000 brethren in the West India islands and they formed themselves into a procession. They got their glorious banners, with their heart-inspiring mottoes raised, and they walked with rejoicing hearts through the streets of Philadelphia.

Did the white people rejoice that the negroes were coming up from degradation? No; that simple procession raised the spirit of murder in that city, and they had not proceeded more than two streets before they were fallen upon by a ruthless mob – their banners torn down – their houses burned with fire – their temperance halls levelled with the ground, and a number of them, by force of brick-bats, driven out of the city (Oh! Oh! and ‘Shame.’) This was the condition of the poor free-coloured people in that land of the free and home of the brave. (Hear, hear.) The coloured population cannot move through the streets of Philadelphia if they have virtue and liberty on their banners – if they have virtue, liberty, and sobriety, they must be pelted with brick-bats. Let them go through the streets, however, poor, mean, pitiful drunkards, and then the pro-slavery people will smile and say, ‘Look at that poor fellow, it is very evident there is an impassable barrier between us and them.’ (Loud cheers.)

[Douglass’s Own Former Fondness for Drink]

I used to love the crittur. I used to love drink – That’s a fact. (Laughter.) I found in me all those characteristics leading to drunkenness – and it would be an interesting experience if I should tell you how I was cured of intemperance, but I will not go into that matter now. One of my principal inducements was the independent and lofty character which I seemed to possess when I got a little drop. (Laughter.) I felt like a president. (Renewed laughter.)

By the way, let me tell you of an illustration of my own feelings of a man who had similar feelings under similar circumstances. When he got a drop he felt as if he was the moderator, or judge, or chairman of a society – or one who has the responsibility of keeping good order. He happened one night to be going home across a field a little top heavy, and he fell near to a pig-sty. After laying there for a time he got very cold, and he crawled into the sty, and the old occupant being out, he laid himself down in her bed, and made himself quite comfortable – (laughter) – until the return of the old creature with her company of young. A gentleman chancing to pass that way had his ears saluted with the cry of ‘order, gentlemen, order’ – (laughter) – on which he went into the sty and there he found the old occupant of the sty with her young, trying to get the fellow out of the bed. (Shouts of laughter.) I also used to feel something like the president of a pig-sty. However, I was cured of that.

Here Mr Douglas [sic] related an amusing anecdote about a colony of rats, from which he drew a very appropriate moral bearing on the question of moderation and drunkenness; and, after a few further remarks, concluded an able address amid loud and protracted cheering.

Mr VINCENT, on coming forward to address the meeting, was loudly cheered. When the applause had subsided, he said, his mind was always so seriously impressed by the bare utterance of the sacred word ‘Liberty,’ that he confessed he knew not how to express to them the deep emotion which he felt, after listening to the powerful oration of their eloquent and honoured brother, Mr Douglass. (Applause.)

He (Mr V.) belonged to a class of men – a growing class of men – who believed that the general interests of mankind were identified with the sacred cause of freedom, and although he had often pronounced it as his opinion that despotism, under all forms and circumstances, crushed the body, shrivelled the mind, and enslaved the manhood, he believed that in the darkest Egypt ever known, the free spirit of man would arise to lead the brotherhood out of bondage, and to prepare the way for a glorious freedom. He had risen to-night to give his humble support to a principle which he believed to be adapted to aid the enslaved and oppressed people of all countries to recover their own manhood, to exalt their own minds, to improve their own morals, and to reform their own manners, and thus to fit themselves for the possession of every rightful privilege which God intended his creatures to enjoy.

The sentiment which he was called upon to expound was – ‘The moral and intellectual tendencies of the Temperance Movement – Personal reform the solid basis of national improvement – and the duty of the friends of free commerce to exert themselves in aid of temperance principles.’

Now, who could look to the actual condition of the numerous people of this country, without seeing the necessity of every effort being made, that could be made, to advance their morality, and to increase their intelligence, and thus to give a tone to the society of a nation so signalised for its wealth and power. In this great nation, which could boast of so many illustrious names connected with every department of human learning, was it not deplorable to know that the mass of the people, in many instances, presented that aspect of moral and intellectual degradation, which was not less fatal to the character of their country as a whole, than injurious to the unhappy victims themselves? Who could look to the immense mass of the people – both the agricultural and manufacturing population – without discovering that the body of the people themselves – their own ignorance and debaucheries – their own reluctance to improve themselves – were at the very root of those evils by which they were desolated. Who did not see that those intemperate and gross habits, which it was the object and privilege of the temperance movement to desire to destroy, were blended with the institutions and long-established prejudices of their country?

To-night, many important principles had been enunciated in connection with the temperance movement. It had been pointed out as a means of prevented drunkenness. They had been implored to save the drunkard from his desolating career. They had been told that temperance produced social and domestic comfort and happiness, with all their attendant blessings – that it was the child of virtue and the offspring of religion. (Applause.)

He regarded the ignorance, wretchedness, and vulgarity of his fellow-countrymen as being created and fostered by their drinking system, which it was the ardent desire of the advocates of temperance to destroy for ever. Who could look at the population of a city like this without discovering the close connection between sobriety, intelligence, and virtue, and drunkenness, ignorance, misery, and vice? No one could walk through the streets of Glasgow, when he left this hall, without not only meeting drunkenness and dissipation, in all their various forms, but they would meet with such a grossness of manner, a vulgarity of speech, and a want of all appreciation of morality or decency of every kind – that they would be more than ever satisfied that no teaching nor attempt at reformation could ever produce any apparent impression on the character of these classes until they had rescued them from the deplorable temptation of drunkenness – until they had called back their wandering manhood – and made them to feel that they were still in the possession of those faculties which God had given them for the noblest purposes. (Cheers.)

He was of opinion that there was no way of improving those faculties without the entire destruction of the vice of dissipation, by which their moral, physical, and intellectual natures were prostrated. He was one who regarded the advancement of the people in intelligence and virtue is of all things the most important. Drunkenness in itself was a most deplorable evil, and as philanthropists, they were called upon to resort to every proper means to extinguish it; but when they looked at the incalculable evils which it produced – when they recollected the facts brought before them by the gentleman who preceded him that the slave was not looked upon with so much contempt when he enslaved himself by dissipation, and enabled his master the more easily to hold him in bondage – it should strengthen their determination, if that were possible, to banish drunkenness from the land.

It was the same in this country with the working man as it was with the slave in America. When the mechanic who bore the badge of labour – not the useless badge of some empty royalty or worthless aristocracy – but the badge which was the heraldry of that power which first felled forests and created cities – when he degraded himself by drunkenness, how often had they heard the supercillious sneerer exclaim, ‘Go to now, how can we give that man the privileges of a free-man?’ (Hear, and cheers.)

The truth was that the more the temperance movement was known, the more would the friends of the cause increase, and the more enthusiastic would they be in their endeavours to reach the end which they had in view. The temperance movement aimed not merely at the conversion of drunkards, which was sometimes a difficult task, but from experiments which had been made, proved to be by no means impossible, but it aimed at the preservation of the temperate. It aimed at producing a better educated population, at a greater refinement of manners, at a closer and more consistent regard to all the decencies and refinements of life, and at elevating the population from their present condition into that state in which they would be able to appreciate all the privileges and advantages that the accumulated experience of the world could give to humanity. (Great applause.)

The temperance movement meant the true system of levelling not by pulling down the mountains, but by raising the valleys; and it meant by the enunciation of that noble sentiment to teach the masses that just in proportion as they became more abstinent and virtuous, and acted more in accordance with the dictates of their higher nature, so in proportion would they be able to enjoy the natural advantages with which they were blessed, with all the enjoyments attendant upon the possession of good health. How vast and important, then, was this movement?

Who could look at the ignorance and wretchedness which prevailed so extensively without seeing that there was a close connection between these evils and drunkenness? They could not go into a close in Glasgow where they would not encounter a want of cleanliness and a want of education, which it was painful to witness. If they talked to the mass of the population congregated in these localities of the benefits of education, and cleanliness, and refinement, they would stare as at one who was speaking a language which they could not comprehend. If they wished to reach this class, they must remember that they could not raise themselves from their degraded condition. Here and there a man might be found who had the nature, power, and energy to raise himself; but, as a whole, this population must remain as it was, unless some means were used for their emancipation.

Every great movement which was of advantage to the world was brought about by the piety, the genius, and the patriotism of mankind, and without such interposition it could never be expected that the poor degraded drunkard and those to whom he was allied could of themselves get clear of their own debasement. If they wished to aid them, therefore, they would do all in their power to strike down the drinking system of the age. This could not be done by condemning it with their words merely, but by their own personal abstinence from the article which produced that debasement, and by their own personal exertions to raise the mass of drunkards from their deplorable degradation. And if he were asked by them if he believed the great mass of the people were to be improved by this moral action – that opened upon in this way they would soon rouse to have a higher regard for morality and the necessities of life, he would say, he did. (Applause.)

There were many causes in the world which contributed to the debasement of mankind. He believed that despotism, under all forms and shapes, was one of the most powerful agents of work for that purpose. He believed that despotism tended to debase the intellect, as well as to enslave the body; that it was the parent of ignorance; and that it induced men to become eventually the forgers of his own chains. He believed that the drinking system impeded the march of improvement and reformation; and he was as much convinced of the capability of improvement of the most debased, as he was convinced of the existence of a God; because he knew that he belonged to the human family, and consequently was embued [sic] with those elements of social progress which were the characteristics of his race; and just so soon as the nations of the world put in operation the light of their common Christianity, so soon would they approach the time when this great reformation would be fully realised. (Applause.)

There was something in this temperance movement exceedingly worthy of consideration, not only on account of its tendancies [sic], but because of its present applicability to the wants of the population. So soon as it was made manifest that there was no occasion for the use of intoxicating liquors, and that the intelligence, and virtue, and patriotism of the country were ranged on its side, so soon would it be made evident to upper and middle classes, and to great bodies of the working men, that the destruction of the drinking system would not only banish drunkenness, but would increase domestic comfort, alleviate misery in many of its most hideous forms, dispel ignorance, and become the lamp of civilization, infinitely powerful in producing a brighter system. (Applause.)

So soon as they great effects were accomplished, the population would almost universally join in carrying their cause, and in improving their own condition, and not be content to sit down and ask themselves what the Queen, or the House of Lords, or the Parliament, intended to do for them, when they had the elements of this revolution lying scattered around them. (Applause.)

They were not to suppose that he underrated the value of any national reformation. On the contrary, he believed that no system which interposed a single barrier in the way of the people’s progress, or to the freest and most extended commercial intercourse, should be allowed to exist – that it ought to be thrown down, and the sooner the better – (great applause); but this much he was convinced of, that if the people were possessed of the true moral power consequent on the development of a purer system, they would possess all the strength and vigour of the full grown man, as compared with the stripling, and spurning the puny barrier standing between them and the green meadow which they wished to walk in, would leap the barrier, and walk on in their own gathering strength to the full possession of all that could bless them. There were many important considerations just now which this movement pressed home upon the attention of the people, in addition to its being a present and practical means of improving their morals and increasing their intelligence.

He agreed with a previous speaker, who said, this was indeed an age of agitation. It was an age of popular movements – an age of progress – and they had lived to see such remarkable changes amongst public men, that a few years ago they could not have believed it.

Five or six years since, he went down to a small agricultural borough near Oxford, and offered himself to the constituency. His opponent was an intelligent – an exceedingly intelligent – gentleman, and he seemed astonished that he (Mr Vincent) should have the insufferable impudence to stand up in the face of a thorough-bred born legislator to oppose him. He recollected, his opponent marched up to the hustings with his supporters, under the rustling folds of a silk banner, most beautifully got up, and presented to him as a staunch Conservative of all that was noble and excellent, and as one that would support the views of the agriculturists. There was a motto upon the banner and one which he would never forget – it was ‘Peel and Protection.’ (Great applause and loud laughter.) What most remarkable changes had taken place since that time. That might be called the good old time by the enemies of human progression, although it could scarcely legitimately be called so, because it was generally understood that the genuine good old time, was during the reign of George III. (Cheers.) The parties who claimed protection seemed to have some sort of idea that the country could not get on with plenty of food, and that a surplus of potatoes would destroy the morals, weaken the patriotism and blight of intelligence of the people (ironical cheers); and they come forward with that beautiful philosophy to support the system, exemplified by one of their number in the House of Commons on Monday night, when he declared that he liked ‘Peel and protection, but not superfluity and glut.’ (Great applause.)

There was at present a feeling in the minds of statesmen, that the social well-being – that the moral interests of the people could no longer with safety be overlooked, and a movement had been commenced in accordance with that policy – the movement for the improvement of the sanatory [sic] condition of large towns. Mr Beggs had alluded to the subject, and he (Mr V.) looked upon the movement as one calculated to effect a great improvement in the condition of the working-classes. This question of cleanliness had been raised by Mr Simpson of Edinburgh, and its importance was incalculable. After referring to the movements of Sir R. Peel on the question of protection, he said, he (Sir R. Peel) had turned and turned so often that he hardly knew himself, but he (Mr Vincent) had no objection to a man turning when he turned in the right direction. The right honourable baronet, however, had created for himself a kind of popularity – placed himself in a position as it were – so that people looked on him now as sailors looked at the vanes to see which way the wind blows.

This was an illustration of that fact, that they were living in an age of agitation – in an age of progress. They had passed the period when cabinets and councils, or coteries of men, could mar the advancement of humanity. It was a glorious thought, that the public opinion of the nation would ere long be the ruling power, and that principle, enlightened by the gathering intelligence of the population, would be held sacred throughout the world. In this country they had not the advantage of living under a republican form of government, like the people in the United States, but he had far more reliance on the virtue of the people than on any mere form of government which man could make.

Here, then, they had a movement which gave them the means of accomplishing a great good, and it could be brought about without any expensive sort of process. Popular assemblies had to be convened, and large sums of money had to be spent to effect any great national movement; but here they were only required to be the agents of their own personal reformation. All would be benefited by it. The moderate drinkers would be benefited by it. The man who spent £10 or £20 a-year upon intoxicating drinks would be immediately benefited by it. The working men of the nation would derive an incalculable amount of good by the adoption of that principle.

Let the mechanic calculate the large proportion of his money which he expended on drink. He did not ask him to make the calculation to half a farthing as they did with the national debt, but to put down the amount in a round sum. Let him then summon the republic of his own household – place his wife in the chair – summon the Lords and Commons in the shape of his little children – and, as Chancellor, come forward at once and make his statement. His wife would look perfectly bewildered as her dear John grew eloquent on the curtailment of the domestic expenditure and might think at first that he had grown mad; but he could plead high authority for his change of opinion. (Cheers.) He might stand up for the undoubted right of changing his opinions, and when he fortified his opinion by allowing that economical housewife what an amount of money she would have in her pocket by the change, there were ninety-nine chances out of the hundred that her eyes would sparkle with delight, that she would say, better late than never, and without any delay or reliance on the forms of this or that house, he might at once move for leave to bring his bill to abolish these expenses altogether. (Applause.) And he was perfectly certain that the bill might be passed through its first, second, and third readings without meeting with any opposition in parliament; and he was sure that in an overwhelming majority of instances the head of that family would affix her signature to it as with much pleasure as ever royalty could feel on giving its sanction to the most beneficial enactment (Cheers.) Here was a valuable plan of present reform which must commend itself to the conscience – which must commend itself to the judgment – of every rational individual. (Hear, hear.)

Before he sat down, he would say a word as to commercial reform. They were called upon in this age of progress to show that they wished those valuable changes to be productive of good to the people of this country, and that they were ready to give their support to everything which would fit the people for the enjoyment of those great advantages. Commercial reform, with all its advantages, could only be fully enjoyed by those who were sober in their character; they ought to rescue the depraved part of the population, therefore, from the evils with which they were surrounded, and accompany their measures of commercial change with the spread of morality and the growth of virtue. He invoked, therefore, their united energies on behalf of the temperance cause. Let their motto be, ‘Onward, onward,’ and they would soon overturn all that stood between man and the consummation of his righteous hopes.

Already they had made a great advance from the time when feudalism first receded before the advancing power of trade and commerce, from the time when Christianity first unveiled her spiritual and moral truths – from that time to this – they had been growing stronger and stronger as time advanced, giving evidence, from the accumulated experience of ages, of the impossibility of this human progress being arrested. He implored them to let themselves be signalised by their attachment to virtue, and love to the poor and destitute, and escaping from the night of ages, look back to that gloom with the cheerful consolation that they are approaching the light of a glorious day. (Great applause.)

Let them bear in mind that the destitute multitude, whose energies are asleep, must be roused up unless they wished them to become drags upon the wheels that were bearing them onwards, and if they only played this noble part, they would advance forward with accumulated velocity to the full meridian of that glorious day which the people would share with them. Already he thought he felt a foretaste of the dawning day of freedom – that freedom which would come for the masses in their own country, and for the enslaved of all lands. [(]Cheers.) It would come for the over-worked and starving artizans at home – it would come for the enslaved men of America – it would come for the Siberian exile in his dreary mine – and the enslaved of every land would hear the glad sound of freedom reverberating from hill to hill to waken up humanity to prepare for the full glory of that noontide effulgence, when liberty and all its concomitant blessings would be the birthright and portion of the whole human race.

Mr Vincent resumed his seat amidst loud applause.

Mr ROBERT REID spoke as follows:- For nearly twenty years have the temperance reformers been energetically prosecuting their work, and during that period their most sanguine expectations have been fully realized; it is evident, however, that the accomplishment of their work must be the result of long and laborious efforts – truth is gradual in its progress – the man long accustomed to the profound darkness of the dungeon, cannot at once endure the full effulgence of a meridian sun, neither can he who has been trained up in the indulgence of pernicious practices, be induced at once to admit the full claims of the truth.

The drinking system is of ancient origin – for many centuries it has been associated with the habits of the people – unobstructed in its operations, it has become incorporated with the entire framework of society, and consequently we have no reason to expect its overthrow without the most prolonged and arduous effort. I trust, however, before I resume my seat to show that the temperance reformation is much further advanced than most people imagine.

The work which the temperance reformers undertook was new in its character, and consequently they groped for a time in the dark; a considerable space was necessarily occupied in learning; they themselves were to a very great extent under the influence of the very system they were seeking to overthrow; at first their discoveries were partial, but they were sincere, and what they knew they did, and as they laboured their knowledge increased, and the clouds of prejudice and custom which had so long separated their minds from the full light of the truth, were gradually dispelled. The history of the temperance movement is full of interest.

The early promoters of it were struck with the fact that a great evil had risen up in the community; they could not tell from whence it had come, but they saw that it threatened the destruction of everything good in society. The feeling was that something must be done to avert impending destruction. Their attention was naturally drawn at first, to the more outrageous features of the evil; they saw that men gratified their depraved appetites by the use of ardent spirits, they examined these liquors, and found them to contain the very essence of destruction, they therefore concluded that if these distilled liquors were driven from the community that their object would be accomplished. Like men in earnest, they set vigorously to work, they laid down as the foundation principle of their operations, this proposition – ‘abstinence from things pernicious, and moderation in things beneficial.’ On this sure foundation, on this broad and rocky basis, they began to rear a magnificent structure, and to remind you how they laboured, and to secure one hearty burst of applause, I have only to mention such names as Edgar, and Collins, and Dunlop, and Kettle, and Bates. Sir, under these men, giants in those days – the building began to rise majestically notwithstanding the jeers of an unthinking multitude.

All of a sudden, a number of the labourers struck work, threw down their tools, and ran, their heads got giddy as they looked from the heights of their own workmanship on the wicked world they had left, they began to think they were going too far. Saw strange sights about them, and fearing if they went much further, they would never get down again, they took to their heels and ran.

A number of the labourers, however, stood fast, they had full faith in the foundation they had laid, and resolved to finish the magnificent structure. It was necessary, however, that additional hands should be procured, and accordingly advertisements were put out. ‘Wanted, a number of stout, active young men, to finish a national monument, wages good.’ I had the presumption, along with a number of others, to make application, and had the good fortune to be taken on.

This change of hands gave a freshening impetus to the work, and the erection went on nobly; the cause of the schism in the temperance ranks was the discovery that fermented liquors had as much to do with intemperance as distilled ones. This was the signal for a general attack. The moderate drinking portion of the community turned out to a man; and, headed by Dr Edgar, made one desperate effort to overturn the temperance structure. The Dr, however, had not the energy in his heart to destroy the magnificent building of which he had been so honoured a founder. Sir, the loss of such men in such work as this is deeply to be lamented: we can ill want the assistance of such energetic minds as those of Dr Edgar of Belfast, and Mr Collins of Glasgow; but there is one consolation which hope affords – they are still alive,

‘And he who fights and runs away,

May live to fight another day.’

Of one thing I am certain, that when they do return to the temperance ranks, they shall secure a hearty welcome, and shall find those now labouring willing to forego everything but principle, to secure their hearty co-operation.

It is a well-known fact that many who adopt the total abstinence pledge violate it: to discover the influences which produce such a state of things is, to those interested in this movement, a deeply interesting subject of investigation. I believe there are few Total Abstinence Societies in the country but could number more members six years ago than they can do now. Why is it so? We are driven to the investigation of this point. Did those who adopted the pledge, and then violated it, intend to keep it? They did. They were truly resolved to keep it; and if questioned on the point they could give no satisfactory explanation of the circumstances which drove them back to their old habits. In the promotion of this temperance reformation we are often doomed to have dragged from our midst those who had been the objects of our most earnest solicitude, and who were useful in carrying forward our plans. Perhaps we have succeeded in rescuing a noble spirit from the thraldom of intemperance, and he, grateful for his deliverance, has felt anxious to contribute his mite towards the accompaniment of our purposes. So long as he remained among the zealous friends of this movement all went well with him; but if, in an unthinking moment, he allowed himself to be brought under the influence of those whose position in society gives a tone of respectability to whatever they sanction, and who are giving the influence they thus possess to support the drinking customs, however trifling that support may be; then, ten chances to one, he becomes their victim – his zeal begins to end – a desire to drink moderately, like his minister or his master, gains the ascendancy, and a few short days find him again indulging in his old and ruinous practices.

Scarcely a day passes without bringing to our notice cases of the kind to which I refer. We have not unfrequently been called upon to witness a member thrown out of a moderate drinking church for his intemperate habits, and given up by his brethren as hopeless. The Total Abstinence Society has taken up the case, and applied their remedy. They find it eminently successful. The man not only becomes changed in his habits, but his home assumes an appearance of comfort, and his family of happiness, which they did not formerly exhibit, and the man himself a desire to lead a useful and Christian life. So long as he mixes with zealous total abstainers, all goes well: he was fired with their zeal, and they are encouraged and stimulated with his. A desire, however, enters his mind again to return to the bosom of the church from which he had been excluded; he makes application, and is willingly received. His circumstances are now changed, he substitutes the fellowship of professing Christians, who are devoting the great influence they possess to stamp the drinking customs of our country with respectability – who are casting a sort of sacred charm around them – he substitutes this sort of companionship for that of those who had dragged him from the fearful pit of dissipation, and the awful and fatal results of his conduct requires but a few weeks or months to exhibit themselves – he is thrown off his guard by beholding this drinking system associated with the religion of our land. He attempts to drink moderately, as he finds his Christian brethren doing – his old depraved appetite thus returns, and he unhesitatingly yields himself a willing victim to his enslaving influences.

A very great mistake exists in the public mind as to the character of intemperance, and the courses which tend to its promotion.

For instance, nothing is more common than the remark, that if government would put down those low tippling shops, and use means to drain the community of these victims of intemperance that are so numerous around us, we should soon be freed from this evil. Now, this statement goes upon the supposition that those things are the causes of intemperance, whereas they are simply the result of it; they are but the excrescences of the system; neither the drunkard nor the low tippling shop possess any influence in the criminality, and, if they stood alone, their tendency would be to create in the young and unvitiated mind an absolute loathing of drink; but while the young are trained up from their very infancy to abhor drunkenness, they are at the same time educated in the very practices that carry them gradually and unsuspectingly into that very vortex of intemperance of which they had been so carefully warned, and which they had attempted to avoid.

The secret of the matter lies in the early domestic training in the drinking and drinking customs. The implements of drinking are associated with the earliest recollections of the young; their tender minds become early impressed favourably with practices in which their parents are regularly indulging, and this added to the little drops of liquor administered to the infant at its very entrance on life, lay the foundation of desires and habits which must necessarily lead on to intemperance, if not avoided by some preventive influence, such as that supplied by the temperance principle. Men do not so much require to be lectured on the evils of drunkenness as on those customs and practices which lead to that evil; in fact there is a danger of misleading the mind from the proper subject, by holding up to public gaze the horrors of drunkenness, while the mind is kept in the dark as to the proper way of avoiding the evil.

If we wish to deliver our country from the thraldom of intemperance we must strike at the root of the evil – we must seek the entire removal of those practices which possess the tendency of consigning to ruin those who indulge in them. The drinking system of our country must be regarded as the source from whence this evil flows. Everything, then, which tends to give respectability to that system must be regarded as preventive of the evils of intemperance. The greater the influence and standing of the man who gives his sanction to the drinking practices, either positively or negatively, the greater will be the evils which flow from it, and the greater the guilt of him who thus applies his talents to the worst of purposes.

I cannot here refrain from quoting the language of our late lamented friend, Dr Edgar of Belfast. Its elegance and truthfulness must recommend it to all:-‘Who manufacture intoxicating liquors? The temperate. Who sell intoxicating liquors? The temperate. Who give the respectability to the whole of the courtesies, and permanence to the whole of the customs and practices which constitute the school of drunkenness? The temperate. What is the chief apology for drunkenness? The moderate drinking of the temperate. What is the chief cause of drunkenness? The keeping of intoxicating liquor as a necessary of life in those families who abhor the sin of drunkenness. The great discovery which now flashes across the world with the lightning’s brightness is, that the temperate are the chief promoters of drunkenness.’

If these remarks be true, then it follows that we have infinitely more to dread from the wine-glass on the table of the pious Christian minister, than we have from the drinking practices of the lowest taproom, or the most abandoned inebriater [sic]; for in the former case, the biting serpent and the stinging adder are hid amid the thousand influences that surround it – the influences produced by the man’s standing in society, and by the high esteem he has acquired in your estimation as a teacher of the truth. The comfortable dwelling, the happy faces you see at that table, the presence of men who have reached a high position in the religious world – all go to convince you that moderate drinking, after all, is not so bad as it is called. You taste the liquor, and become confirmed in your belief, for you find the destructive principle associated with tastes and flavours that render it palatable and pleasant. Let the religious and influential portions of the community continue to give their sanction, in any shape, to the drinking practices of our country, and intemperance must, in spite of all our efforts, go on increasing and destroying; but let them manifest their unqualified disapproval, by withdrawing their entire support, then must the entire drinking system become a reproached and disrespected thing, and drunkenness, its natural result, must speedily vanish from our land. We state it, as an incontrovertible truth, that the more influential a man’s standing is in society, the more destructive does his example become when it is given in any way to support that which is evil in its character.

This is the only chance of success. You may talk against drunkenness as much as you please, but the evil will go on so long as you allow the springs from which it flows to remain unexposed; but let the professedly great and good withdraw their sanction from this work of darkness, and those works will speedily disappear. (Great cheering.)

Permit me for a few moments to turn your attention to the means frequently in use by the temperance reformers:- The only one by which the temperance reformation can possibly be accomplished, is by spreading information on the point, enlightening the public mind as to the real character of the evil with which we are contending.

We look upon the platform and the press as the two great instruments by which this work is to be accomplished. The association which has called us together to-night, is devoting its almost exclusive energies to these modes of operating: the Publication Committee are exerting themselves to improve the temperance literature of the country; they have originated a monthly temperance magazine, entitled the Scottish Temperance Reviewer; for size it is one of the cheapest publications of the day; it numbers among its literary contributors some of the most popular British and American writers, and promises ere long to have a most extensive circulation; they are also making arrangements for the publication of a uniform temperance library, this undertaking will consist of a series of handsomely finished volumes; the matter will be entirely original; each volume will embrace a separate department of the subject; the authors of those volumes will be the most eminent writers on the abstinence question, both in America and in this country; no expense will be spared in making the various productions worthy of the most extensive circulation; and with the view of bringing them within the reach of the humblest, the price of each volume will not exceed one shilling. The Publication Committee are also devoting their attention to other schemes of a kindred kind.

Then, as regards the advocacy department of our work, I have only time to refer to the exertions of Henry Vincent in the promotion of temperance principles in Scotland during the past eight months. As Secretary of the Temperance League I have been cognizant of every meeting at which he has been present during that period, and can therefore speak with considerable confidence as to the result of his labours, from a calculation which I have made since entering this meeting, I find that at least 150,000 persons must have listened to his eloquent appeals on this question during the past eight months. I hesitate not in saying that his tour is unprecedented in the history of the temperance movement in Scotland. Large numbers of persons have been induced to attend those meetings who could not formerly be induced to attend similar gatherings, and Mr Vincent has done very much to break down these prejudices to this movement which have so long existed in the minds of the middle and upper classes of society. I regret that he is about to leave us, and I am sure you will join with me in the wish that he may soon return to this part of the earth to prosecute still further that work in which he has been so successfully engaged.

We have on this platform another gentleman, Mr Thomas Beggs of Nottingham who has been induced to visit Scotland for a period with the view of following up those efforts which have already been made. Although Mr Beggs is a comparative stranger here, yet his name must be familiar to all who take an interest in the temperance reformation, as one who has for a long series of years been a devoted and successful promoter of temperance principles in England. He has for a considerable time been directing his attention to the health of towns question, and his lectures in Scotland will have a special reference to the connection of that inquiry with the temperance movement; but as that gentleman is on the platform, and about to address you, I will refrain from making further remarks.

In conclusion, let me earnestly entreat those whom I now address to give their hearty co-operation to this great work in which we are engaged. The labourers are comparatively few, and the work is too great for them unaided, to accomplish. To the younger part of the community we look especially for support. Your arrangements for life are not completed; your habits are not fully formed; your minds are more susceptible of impressions than are those of persons more advanced in life; let us then take advantage of our circumstances. Instead of spending our lives in those trivial and foolish pastimes that generally occupy the attention of the young, let us cultivate those dispositions and habits that will fit us for eminent usefulness.

Let us remember that Christianity is a practical system; that its language to us is not to send others to do our work, but to go ourselves, if we would raise the degraded we must go down to them. We must leave our kid gloves and condescending looks at home before we can gain the confidence of those who need our aid. We must impress them with the belief that we are in earnest; that we really seek to make them better and happier than they are; in fact we must for the time become poor, that they through our poverty may become rich.

Let us cultivate a moral independence of character, then instead of us occupying a position so often occupied, but one unworthy of our immortal natures, I mean lending [= bending?] to circumstances, we will stand unmoved, and we will be enabled to make the most unfavourable circumstances bend to the accomplishment of our designs.

Abandon the idea that the degraded masses around you are incapable of improvement. True, indeed, they are the victims of a fearful bondage, but we ourselves have had much to do in forging those chains with which they are bound, and therefore it is doubly our duty to labour for their emancipation. You will find among your degraded countrymen some of the noblest spirits crushed indeed beneath a fearful mass of evil, their moral energies are prostrated to the very dust, but they are capable of being elevated.

Go, whisper into their ears that he who would be free has but to will it. Tell them of the glories of freedom. The grand idea that man must be his own deliverer will strike upon the mind with convincing power; the dormant energies of the soul will be awakened; the vital spark within them will be fanned into a flame; the mighty incubus of evil that now holds them down, will vanish like a vision of the night, and once-degraded humanity will stand before an admiring universe, emancipated and free.

The meeting separated at a twenty minutes to twelve o’clock.

The company were well supplied with excellent fruits by Messrs Mathie & Co, fruiterers, Buchanan-street.

Glasgow Examiner, 21 February 1846

SCOTTISH TEMPERANCE LEAGUE – TEA PARTY IN THE CITY HALL

On Wednesday evening a tea party was held in the City Hall, under the auspices of the Scottish Temperance League, when the area of the building was filled in every part by a most respectable company, nearly one-half of whom were ladies.

The Rev. Dr Bates occupied the chair, and on the platform we observed many influential and ardent friends of the temperance cause. After a service of tea, with its usual accompaniments, the Chairman opened the proceedings with a short and appropriate address on the rise and progress of the temperance cause.

It was a cheering sight for him, he said, who had seen the movement in its infancy, to witness the present meeting, and more especially after the reception it encountered at the outset. Many discouraging remarks met the ears of its advocates, and many gloomy anticipations were put forward to dishearten them. Still, however, the work went on; and now, after twice seven years had elapsed, he had just to point to that splendid assemblage as an answer to all those gloomy predictions.

Among the objections urged against this society it had been assumed that it had an unfriendly aspect towards religion. Now it seemed to him passing strange how it ever could be supposed that sobriety and religion had any repugnance to each other. If there had been advocates of the temperance cause who had been unfriendly to religion, he should say they had been grievously mistaken, because he was convinced that no reformation could be permanent that was not based on true principle and religious truth. But it was marvellous that the friends of temperance could suppose that the temperance reformation was unfavourable to religion and morality. He believed that some things might have given a colour and a pretext for such insinuations, but they had not ground to stand upon. It had sometimes been the case, that the advocates of the temperance cause not finding themselves supported by the friends of religion – by ministers of religion – as they ought to be, indulged in a strain of censure and invective which had done no good to their cause, and which they would not have used had they considered the effect; still, however, their language did not invalidate the principles, and no sensible man would think less of a good and great movement, because it might have a few injudicious supporters.

After a few further remarks, shewing the necessity of charity, and forbearance, and persuasion being exercised by the advocates of temperance, the chairman concluded by introducing –

The Rev. Wm. Reid of Edinburgh, who on rising was received with loud cheers. After expressing the pleasure which he felt in looking upon this assembly, and recognising the faces of many old friends with whom he had laboured in times past for the reformation of the drunkard – the rev. gentleman proceeded to speak to the sentiment intrusted to his care, viz.:- ‘The spirit in which the Temperance Reformation ought to be conducted.’

He commenced by congratulating the chairman and himself that of the tens of thousands of poor drunkards who had gone down into destruction since the commencement of this movement, none could blame them for their ruin – and with this simple conviction he felt more gratification than in the misnamed enjoyments connected with the drinking cup. It became them however, not to feel satisfied merely that they had led no one into the path of folly and of vice, but to gird themselves anew for the conflict, and to persevere in their exertions until the cause was triumphant.

Here Mr Reid proceeded to show that the moderate drinker was equally culpable with the drunkard – and that even those who stood aloof from this movement – when they witnessed the ravages made by the drinking usages of society – were not blameless. The drinking customs which he reprobated, and which called for their interference, entered into every part of the social system. In the workshop, when young men entered upon their business – at marrriages, when they commenced the active business of life – at births, when their offspring were first ushered into the world – at baptisms, and at deaths – these drinking customs were encouraged and promoted, to the injury of the health, the morals, and the best interests of mankind. These he denounced, and called for renewed efforts of their part to put them down.

The Rev. gentleman concluded an eloquent address amidst loud and continued cheering.

Mr James Buffum, of Massachusetts, spoke to the next sentiment – ‘The rise, progress, and results of the temperance movement in America.’ After a few preliminary remarks, Mr Buffum said – The temperance reformation in America commenced about the close of the revolutionary struggle which seperated [sic] her from this country, and was first set agoing in consequence of the conduct of the soldiers, who had bee provided largely with intoxicating liquor during that struggle, and who, having imbibed an appetite for drink, carried it, with all its evil consequences, into the heart of the community. To such an extent was the practice of intemperance carried at this time, that it was feared by many that they would become a nation of drunkards. Intemperance found its votaries in the church, in the congregation, in congress, on the judge’s bench and among every class of society.

There was an anecdote which would show how are the demoralizing practice was carried among professing Christians. There was a church near to where he came from, which had a member of the name of Brown, whose drinking practices were so notorious that the church met to consider his case. After deliberating, they appointed a committee to wait upon Mr Brown with the view of reproving him, and testing his fitness to continue in membership. Now, this committee was composed of moderate drinkers, and Mr Brown hearing of their coming prepared for their reception. He placed a sideboard in the room which he intended to usher them into a quantity of wine, brandy and other liquors, and after their arrival he said he hoped they would excuse him for a few minutes as he had to go out on some necessary business. In the meantime (pointing to the sideboard), he desired them to make themselves at home. (Laughter.) Mr Brown stayed out of the way for nearly half an hour, and the committee, in his absence, did, indeed, make themselves quite at home with the liquor. (Laughter.) So much so, that, when Mr Brown returned, they talked with him for about two hours on every subject but that which had taken them to his house, and they went away and reported to the Church next week that Mr Brown had given them Christian satisfaction. (Laughter.)

About the same time when a church was building in Boston, and when the foundation stone was to be laid, a master builder sent the operatives a barrel of new [sic] England rum. As a return for this very acceptable present, what did the operatives do? Why, they chiselled out the letters of his name on the corner stone. (Laughter.)

In the year 1826, however (the condition of the country in America being pretty much the same in regard to intemperance, as he had seen since he had come here), the friends formed their society, framed a constitution for it, and in only three years from that time there was a wonderful change in that community. But, notwithstanding, they had not then got the right principle go to upon. They went upon the principle that a man might drink if he only drank moderately, and on this account many who joined the Temperance Society were fast proceeding to intemperance. On this plan it was almost as difficult to say when a man drank moderately and when he drank intemperately, as when a pig was put in a sty to say when he became a hog. (Laughter.)

They came at last, however, to the proper principle – total abstinence (cheers) – and under that principle their progress had not only been rapid, but secure and lasting.

Mr Buffum made a few other appropriate remarks, and concluded, amid loud cheering.

Mr Robert Reid of Glasgow, next addressed the meeting on ‘The experience, policy, and aim of the Temperance movement,’ and in doing so, detailed the nature of the means now in operation for the spread of the principles, and the advancement of the cause of temperance. Mr Reid’s statements seemed to give great satisfaction to the meeting.

Mr Thomas Beggs, of Nottingham, then addressed the meeting on ‘The Temperance Reformation. viewed as an agent of civilization.’ and in the course of his remarks adduced a number of interesting statistical details, shweing the effect of drinking customs upon the health and comfort of the people in the manufacturing, as contrasted with the agricultural districts of the country. Mr Beggs’ speech was loudly applauded.

Mr Frederick Douglas, of Massachusetts, (an escaped slave) now rose, amid loud and long continued cheering, to propose the next sentiment. He said, Mr President, Ladies and Gentlemen – I feel proud to stand upon this platform, and with pride regard the reception I have received in standing forward here for the purpose of throwing in my mite towards advancing the temperance cause in Scotland. (Cheers.) The subject announced for me in the programme is the question of intemperance viewed in connexion with slavery. Now, I confess I feel some difficulty in discussing the two subjects, the one in connexion with the other, still, I have a few facts respecting the working of slavery in connexion with intemperance in the United States, which, if they tend to throw light on the subject, it may be of some importance to you.