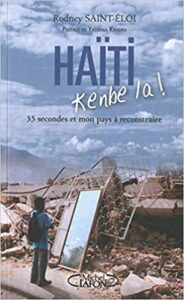

Rodney Saint-Éloi

Haïti kenbe la!

Paris: Éditions Michel Lafon, 2010

Like Dany Laferrière’s Tout Bouge Autour De Moi, this is a first-hand account of Haiti’s earthquake by a Haitian-Canadian author who was in Port-au-Prince for the Etonnants Voyageurs book festival in January 2010.

Neither has yet been translated into English, but they should be. For many years now it has been customary to tag Haiti as ‘the poorest nation in the Western hemisphere’ in foreign news reports, and coverage of the earthquake often reinforced the tendency to treat the country and its people as victims who can do little to help themselves. Neither the sour commentaries of those who blame Haiti’s misfortunes on an endemic fatalism so often attributed to ‘voodoo’ nor the well-meaning efforts of the thousands of NGOs who provide aid ‘from above’ contribute much to the vital task of extending and strengthening democratic participation in a society dominated by a tiny rich elite; indeed, they have been accused of deliberately thwarting it.

Saint-Eloi does not confront this situation head-on. He is a poet and publisher (he runs Mémoire d’encrier in Montréal) not a grassroots activist, and although he returns frequently, he has not lived in Haiti for more than a decade. Accordingly, his perspective is that of a visitor. The narrative begins in media res as he drifts in and out of sleep on the tennis court of the Hotel Karibe where he and the other guests spend the night after being forced to evacuate when catastrophe struck the previous afternoon. In the course of the book, we meet a large cast of characters, including fellow writers (many of them, like his friend Dany, put up at the hotel by the festival) and members of his family, as he moves about the city observing scenes of devastation and the efforts to rescue the living and bury the dead.

Despite the sloganistic title (a popular Kreyòl expression meaning ‘Never Give Up!’), Haïti, kenbe la! is an episodic collection of low-key personal impressions and recollections. Children amuse themselves with water pistols; a woman’s naked body is found the arms of her illicit lover and her husband buries them together; a radio announcer reads out the names of survivors; a policeman who avoids injury because he is late for work; ways of concealing the smell of death; the sound of hymns, prayers; thieves ransacking a displacement camp; journalists taking photos of corpses. The city takes shape through the accumulation of telling details. And indeed Saint-Eloi compares his method of composition to the way his mother in New York synthesizes information from many different sources in order to construct the compelling story of the earthquake she tells him over the phone.

After a couple of nights, he moves out of the hotel and stays with friends in a house overlooking a makeshift camp. They ration their food, but allow themselves a bottle of wine now and again. Before the week is out, Saint-Eloi is offered a seat on a military aircraft flying to Montreal, alongside other Haitian-Canadians – but only those with a Canadian passport are permitted to leave.

He allows many voices to speak – often without comment, giving us a Haiti in which different faiths vie for attention, and a strongly patriotic sense of history coexists alongside a cynical dismissal of current leaders, where the overseas aid represents relief for some and suffering for others, and the possibilities offered by emigration forms the horizon of so many lives. Through the story-teller Grann Tida, Saint-Eloi suggests Haiti has long represented to outsiders either the appealing primitive or the threatening savage, but it has also answered back. ‘Touris pa pran pòtrè ‘m’ (‘Tourist, don’t take my picture’) she says, quoting Felix Morisseau-Leroy’s famous poem, while conceding that it is not likely to have much effect.

Yet if the tourist would read this book, perhaps another Haiti could come into focus, one that is not designed to answer the outsider’s hopes or fears. ‘Resilient’, perhaps, although Saint-Eloi bristles at such an abstract concept. This Haiti is essentially one in which people just get on with things. A Haiti that lives for the present. If you fall, you get up – an attitude illustrated by the new neighbours in the ‘village’ that sprung up near his temporary home in Delmas: Zaka and his friends, playing dominoes, slamming down the tiles, their everyday chat – music, carnival, women, the price of rice and corn – punctuated with bursts of laughter.

But the hero of the book is undoubtedly Franketienne (who in Rapjazz: Journal d’un paria has recently written his own, rather more poetic, tribute to the city). We first meet the writer and artist hard at work rebuilding his house in Port-au-Prince. Later, Saint-Eloi takes a call from him in Montreal. He jokes about the Nobel Prize everyone expects him to win and reads a passage from his new play which is soon to be produced in Paris.

Since his return, he has struggled to resume his old life, haunted by the fury of the goudougoudou. But he emerges from the conversation with renewed vigour. ‘Franketienne had just reminded me that hope is not a utopia,’ he writes. ‘Franketienne had just reminded me that hope was Haitian.’

Some other first-hand accounts of the earthquake are included in Haiti Rising: Haitian History, Culture And The Earthquake Of 2010, edited by Martin Munro.