‘This is not the first time I have been in Glasgow,’ said William Lloyd Garrison to the audience at City Hall on Wednesday 30 September, referring to his appearance there in 1840, following the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. But an earlier visit to Britain in 1833 left its mark on the city too, as Garrison inspired the formation of the Glasgow Emancipation Society, steered since then by its secretaries William Smeal and John Murray. The meeting was chaired by committee member Andrew Paton, Garrison’s host at his home in Richmond Street.

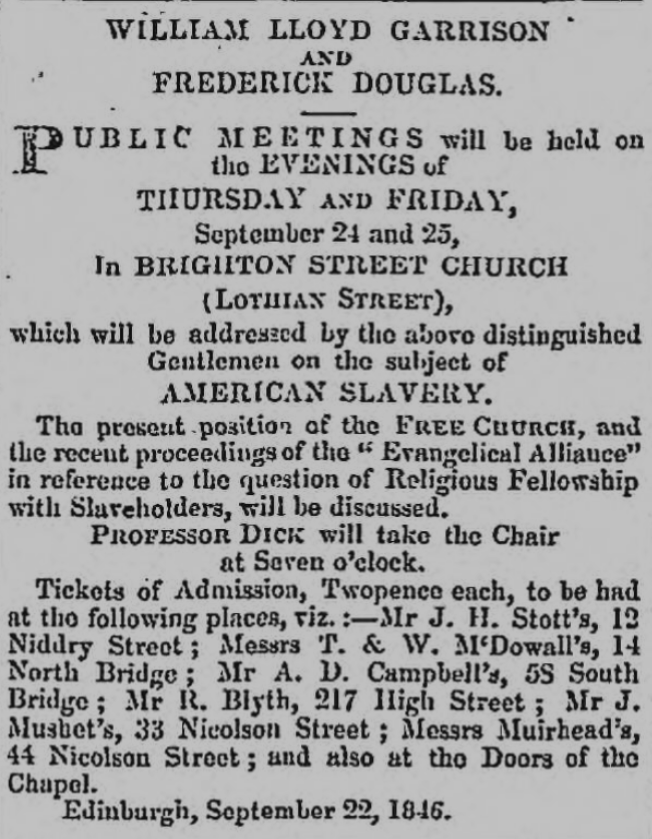

As the main guest of honour, Garrison was allowed to speak at much greater length than Douglass, and while both reviewed the proceedings of the Evangelical Alliance (London, 18 August to 2 September) and the debate on American slavery at the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland (Edinburgh, 30 May), Garrison also responded in some detail to recent reports in two papers supportive of the Free Church – the Scottish Guardian and the Northern Warder – which cast aspersions on their abolitionist campaign.

For an overview of Frederick Douglass’ activities in Glasgow during the year see: Spotlight: Glasgow.

AMERICAN SLAVERY, THE FREE CHURCH, AND THE EVANGELICAL ALLIANCE

A PUBLIC MEETING of the members and friends of the Glasgow Emancipation Society was held in the City Hall, on Wednesday evening, for the purpose of receiving William Lloyd Garrison, Esq., and reviewing the proceedings of the Free Church and the Evangelical Alliance, in relation to American Slavery. The meeting was numerously attended. On the platform we observed Councillor Robert Smith, Councillor Turner, Mr. William Smeal, Mr. John Murray, and many other respectable citizens. Andrew Paton, Esq., was called to the chair, and opened the proceedings.

Mr. PATON said, I thank you for calling me to the chair. Our meeting this evening is chiefly for the purpose of welcoming our friend, William Lloyd Garrison, to this city, on the occasion of his present visit to this country. Mr. Garrison requires no introduction to your confidence; his well-known name is a passport sufficient to ensure for him a warm welcome from every true abolitionist of slavery throughout the world. From the excellent account of the life of Mr. Garrison which has lately appeared in the People’s Journal, from the pen of a very talented lady Mary Howitt,1 many present are doubtless acquainted with the prominent points of his career, and know that sixteen years since Mr. Garrison was so impressed with the clamant unrighteousness of slavery, that he felt called to devote his energies to effect its overthrow. Though possessed of the most slender means, he then started the Liberator newspaper in Boston, to advocate the cause of immediate emancipation for the slaves. In this he has ever since laboured with the utmost fidelity and ability, and with his noble coadjutors has already been successful in bringing about a great change in public opinion in the northern or free states of America. (Applause.)

Mr. Garrison’s unswerving faithfulness, his courage and perseverance in tracing and exposing Slavery through all its defences in Church and State, and in a false public opinion – have, as might be expected, concentrated upon him the attacks and calumnies of all in the United States or elsewhere, who are slaveholders or apologists for slaveholders. One singular instance of the intensity of this hatred against him, is that the Legislature of Georgia did some years since offer, and do still continue to offer, a reward of $5000 for his delivery to them. Mr. Garrison proposes this evening, amongst other objects, to review the position of the Free Church and the Evangelical Alliance, in relation to slavery. I need not say that we have no difference with either of these bodies, save in relation to the course they have pursued on slavery, which, in our opinion, is unfortunately calculated to exert a prejudicial influence on the cause of the slave in America, by throwing around the slaveholder the countenance of religious men, and the sanctions of christianity, whose mission is to ‘undo the heavy burdens, to break every yoke, and to let the oppressed go free.’ (Cheers.)

We are happy to have with us, also, our talented friend, Frederick Douglass, whose powerful pleadings on behalf of his brethren in bonds, are so well known to us, and have interested so many throughout Great Britain and Ireland.

We regret that our friend H.C. Wright, at present in Dublin, has been prevented from being with us on account of his health; up till Monday he expected to be here, but by a letter of that date received this morning, he says that from the state of his health he is reluctantly compelled to stay, as he does not find himself equal to the fatigue of the voyage. We hope for his return to Scotland for a short time, soon.

The annual meeting of the Glasgow Emancipation Society falls to be held about this season, but the Committee have deemed it advisable to defer it for the present, to allow Mr. Garrison, whose stay is limited, more time to bring before us his views on the present position of the cause in America, and the effects which the conduct of the Free Church and the Evangelical Alliance are calculated to have upon it.

Mr. W. SMEAL then read Mr. Garrison’s credentials from the Abolitionists in America, and from the free coloured population in Boston, constituting him their representative.

Mr. GARRISON, on rising to address the meeting, was loudly cheered. When the applause had subsided, he spoke to the following effect:– These are the credentials which I lay before this audience to commend me to their confidence and regard, as the uncompromising friend of universal emancipation; and to all the reproaches and calumnies that have been circulated on the other side of the Atlantic, or that are in circulation on this, I point to these credentials for an answer, and no other need be given. With the oppressed and down-trodden coloured population of America bidding me God speed, I feel that I am indeed a friend of liberty, and that the friends of liberty throughout the world should, instead of endeavouring to obstruct my progress, give me the right hand of anti-slavery fellowship. (Cheers.)

This is not the first time I have been in Glasgow, and, I hope, it will not be the last. (Great applause.) It was my privilege to stand before an audience in the Rev. Dr. Wardlaw‘s chapel in 1840, and I never shall forget the generous and cordial reception given to me on that occasion, as the friend of the oppressed slaves in America. I trust I have never faltered in my course since that period, and that my principles are the same that they were then. (Applause.) The position which I occupy is as hateful to the tyrant now as it was then. The blessings of those who are ready to perish are falling on my head now as they were then. I have not gone backwards, but forwards – not downwards, but upwards; and therefore I claim a warm reception again from the free men of Glasgow. (Cheers.)

I delight to be in this place for very many reasons. After the abolition of West Indian slavery, so far as England was concerned, the flame of emancipation, so to speak, went out, or burnt very low. There seemed to be a general feeling, that inasmuch as the slaves under the British flag were now rejoicing in their freedom, that enough had been done, and that abolitionists should be discharged from any father service. But not so in Scotland – not so in Glasgow. There were free spirits here who began their warfare with slavery not because it was a West Indian question, but because it was opposed to God and the rights of man, and should not be suffered to exist anywhere on the face of the earth. (Applause.) Entertaining those views, they set themselves to the work of overthrowing slavery throughout the world, determined till the last chain was struck from the limb of the last slave not to abandon the conflict. – (Hear, hear.)

– On another account I am happy to be here. I am abolitionist – an American abolitionists – and as such, in common with thousands on the other side of the Atlantic, have from time to time been cheered by your voices, and strengthened by your testimonies. The Glasgow Emancipation Society has done almost as much as the American Anti-Slavery Society. I am not speaking in extravagant terms, but I am saying what I believe, when I sat that you have done a mighty work towards overthrowing American slavery – towards disheartening the upholders of that system – and towards disheartening the upholders of that system – and towards strengthening the hearts of the abolitionists of America.

You did something else, the importance of which has never been sufficiently estimated. I allude to the gift of George Thompson to America, through the influence of the Glasgow Emancipation Society. (Great applause.) Never was aid given at a more timely period, and never was such aid given in similar circumstances, as when the peerless orator – the friend of universal man – was deputed to represent the Glasgow Emancipation Society in the United States of America. And well did he carry out the principles which he had advocated in this country in America. Well did he fulfil his pledge that he would make himself a party with the despised and hated abolitionists, and that he would take his position with the down-trodden slave. (Great cheering.) I need not go over the particulars of his mission to America, with which you are all acquainted, but I may say this, that he was more true to his principles than the needle to the pole, for it sometimes knows vibrations, and he never alters. (Cheers.)

[RESPONSE TO THE SCOTTISH GUARDIAN]

I now beg to allude to an introduction which I have received gratuitously to the Glasgow public, through the columns of the Scottish Guardian, and which I now desire to make use of in my own behalf. It begins as follows:–

We do not suppose it will be necessary for us to trouble our readers much farther with Mr. Lloyd Garrison, Mr. Douglass, Mr. George Thompson, or the other American agitators, – who, it will be observed, have been again attempting to get up one or two meetings in Edinburgh, and may, perhaps, repeat the same experiment in our city. Their own exhibitions afford the grounds of their strongest and surest condemnation, and have speedily brought down upon them in this country the contempt with which they have long been regarded by all good men in America.

Why, you have a strange way of showing your contempt in this country. I have been in the presence of assembled thousands in London, and they have given me the right hand of fellowship – at least I thought so. I have been in various parts of England, and addressed many thousands of the people, and yet with scarcely an exception they have received me with the warmth of brethren, and have done everything in their power to make me understand that we saw eye to eye, and are one in spirit in regard to our abhorrence of slavery. I have met with something of the same kind in Scotland. (Cheers.) I have been at Greenock, Paisley, Edinburgh, Dundee, and in all those places the enthusiasm has been all that my heart could desire, and much more than I could have reasonably expected in view of the defection of the Free Church of Scotland, and their support of slavery in America. (Great applause.)

Then as to the contempt of ‘the good men in America’ – the good men who hold three millions of human beings in chains and in slavery – the good men who have from one end of our country to another embraced the spirit of liberty, and endeavoured to destroy her – the good men who are hunting up apologies for those who are putting women under the lash, and are selling babes by the pound – the vulgar – the disorderly – the chief priests and pharisees – the head and the tail – altogether, have given us their contempt; but why should it be otherwise? (Great cheering.)

I feel I should have to make myself the basest of the base to merit such men’s praise, and I glory in their condemnation. (Applause.) I want no tyrant to praise me. I want the slave to acknowledge me as his friend. That is all I can ask, and it will serve to meet all the minions of tyranny can bring against me, or any other man in a similar position. (Cheers.)

The article in the Guardian goes on –

Mr. Buffum and Mr. Wright (Mr. Thompson’s correspondent ‘Dear Henry,’) have already decamped. The others, we doubt not, will soon follow.

No doubt the writer of this is a brave man. No doubt, when the meetings were formerly held in this place, that gentleman was valiant in coming forward and breading the lion in his den. No doubt, he never skulked – he never took refuge in his own columns where no one else could be heard. (Hear and cheers.) He came here to say ‘Who’s afraid? I will humble these men, or make them decamp.’ He did not come, and he remained away for some cause. Why, it is only ‘the wicked who flee when no man pursueth.’ (Great cheering.)

It is only the Free Church which cannot challenge investigation. It is only the apologists of the Free Church who dread a free platform, and who dare not measure weapons with George Thompson, or men who sympathise with the slave. (Cheers.) Wherever I have been, it has been uniformly announced that our meetings are as free for the advocates of the Free Church as for ourselves. (Hear, hear.) I make the same announcement to-night. (Applause.) This is the way we skulk and run away.

(Great applause.)

As if Mr Thompson was to continue to reside in Glasgow to prove that he is not deficient in valour. As if Mr. Buffum should have to transfer his residence from the United States to Glasgow to prove he is not a coward. A very reasonable man is this editor of the Guardian. The article proceeds, –

Our readers must have observed that the resolution which was adopted by the Evangelical Alliance proceeds upon the same sound and scriptural principles which have guided the proceedings of the Free Church in relation to American slavery. The consequence is, that the Alliance – composed of excellent men, of all the evangelical denominations in Britain, is at once denounced, no less than the Free Church, as ‘an unchristian body!‘ – composed of ‘wolves in sheep’s clothing!‘ – their language is declared to be ‘downright blasphemy!‘ – and their prayers no better than ‘a solemn mockery before God!‘

I tell the Free Church that she must not lay that ‘flattering unction to her soul,’ that she is safe because she has got an ally. (Hear, hear.) I tell her, that ‘although hand join in hand, the wicked shall not go unpunished.‘ (Great applause.) I tell her that although Pilate and Herod are become one for the crucifixion of liberty – that although they have crucified her, and committed her to the tomb, and sealed the doors, and appointed the ‘Guardians and Warders,’2 to see that none take away the body, yet the watchers shall fall to the ground, a resurrection shall take place, and thus the nations of the earth shall be redeemed and disenthralled.

Why, if it be true, as it is true, that the recent Evangelical Alliance has been as base in principle in regard to the anti-slavery cause as the Free Church of Scotland is, does it make out a case in favour of that church? And when two such parties come together, are justice and mercy to go by the board? This Evangelical Alliance, instead of being a support to the Free Church, shall be another millstone about her neck, unless she repents ‘and brings forth fruit meet for repentance.’ (Applause.)

I have now a remarkable fact to submit to you. The article I am noticing continues as follows:–

It is a remarkable fact that, while the Alliance included a very large body of American ministers, of twelve or thirteen different denominations, from all parts of the Union, the whole of these men (with the exception of a Mr. Himes, who is a Garrisonian – and, perhaps, one other individual) were unanimous in earnestly denouncing Messrs. Garrison, Thompson, &c. as ‘pestilent fellows,’ and the greatest possible obstructors of the cause of abolition.’

I have heard that said a great many times. I have heard it from the lips of slaveholders for the last twenty years. The men declaring that slavery is the corner-stone of our American edifice – a divine institution, which ought to be perpetuated – are the very men who affect to grieve that I have retarded the progress of abolition at least 150 years. Now, if this were true, instead of offering 5000 dollars for my head, they would have put that money into my pocket. (Hear and cheers.) They would have asked me to go south of Mason and Dixon’s line. They would subscribe for The Liberator, and not tell me if they catch me, they will hang me. (Cheers.) But when they cannot do that, they affect to grieve that I do what they want done.

The American members of the Evangelical Alliance are the worst foes of the anti-slavery cause. They have no flesh in their obdurate hearts. They are mere time-servers, and popularity-hunters – men who love the praise of men more than the praise of God – men who are striking hands with thieves. (A slight hiss, followed by tremendous cheering.) I don’t know how to meet a hiss, but I know how to meet an argument. (Applause.) Yes, we had nearly seventy delegates in the Alliance – strong men – men of large intellect, and great influence. But then they are also great advocates of the innocency of slave-holding, and man-stealing, and their intellect and influence are given to the side of the oppressor, and against the oppressed, who have few to plead for them. They are, in scripture language, ‘wolves in sheep’s clothing.’ They are men who came here to deceive the British public. They say they are opposed to slavery, and really would do something, but for those fanatical abolitionists. Now, when they go to the bar of God, and are asked why they did not open their mouths for the slave, will they say to God that if it had not been for that infidel Garrison we would have done something, but he stood in our way and we stood still? I do not know whether that apology will do or not, but I have an opinion that it will not be good; for if it be true that the abolitionists of America are injuring the cause, then so much more active and untiring should be those who are not abolitionists to see that the cause should not suffer injury, and that the slaves should be liberated from their chains. (Great cheering.) The Guardian further says –

The solemn judgment of such men, and of all the other various classes of evangelical Christians assembled in the Alliance, is not likely to be shaken by clamour and ribald abuse; and we should think most people, who have any regard to their character, will be cautious how they give father countenance to these agitators in their profanity.

This, Sir, is genuine American pro-slavery. (Hear, hear.) If I had not know that I was in Scotland, and that it is from a Scotch paper I am reading, I should have supposed myself to be in the United States of America, in the midst of slavery, and with one of the American pro-slavery papers in my hand; so true it is, that wherever slavery is to be shielded, the same spirit must be exhibited, and the same low attempts made to cover up with odium the uncompromising friends of freedom. (Great applause.) Can we not settle this matter in a common-sense way without much argument? Nobody denies but that there are three millions of people in slavery. Now, I hold that wherever there is a struggle for freedom there can only be two parties – the one party consisting of the tyrants and the friends of tyranny, and the other party of the oppressed and the friends of the oppressed. No man may say, I am neither with the oppressed nor with the oppressor. There is no neutral ground between them, and you must either be with the oppressed or with the oppressor, whatever protestations may be made to the contrary. (Loud cries of ‘hear, hear.’)

Now, where are the slaveholders in America? They are the tyrants. With whom do they sympathise? With the men who were sent to the Evangelical Alliance, who can travel through the slave states and be welcomed to every table, and be honoured and flattered as the true friends of the south. What does this prove? That they are the supporters and advocates of slavery. (Hear and cheers.) In regard to the abolitionists, how do the slaveholders look upon them? With fear and consternation, and as those determined never to give up the contest on behalf of the down-trodden slaves. Where are the down-trodden slaves? They join their hands with the abolitionists. Where are the slave population of America to-night? Here; with me in the person of that beloved brother. (Cheers.) Every man of them, every woman of them, and every child in slavery, are represented faithfully and truly in the person of Frederick Douglass. (Great applause.) Then as to the free coloured population, who are treated with great indignity wherever they may go in the United States, have I not presented their resolutions to-night, constituting me their delegate? They are here in my person, and therefore the cause I represent is the cause of the oppressed; and hence you, as the friends of the oppressed, will endorse the principles of the abolitionists of America endeavour to carry into effect. (Cheers.)

Since I came to this country I have been admonished by some to be careful of my language, and to deal as gently with this subject as I can. I will do so. I desire to be prudent, and careful, and just, and, at the same time, faithful and uncompromising. I desire to remember that I profess to be the advocate of the American slave. I stand here as the slave of America – as one having the chains of bondage around his limbs – as one destined to be put on the auction-block to0morrow – as one denied all his rights as a man – as one whose lip is stopped by the slave-driver – as one who may not read the Bible – as one who may not hear the Gospel preached – and, standing thus, I will be as gentle under the oppressions I am labouring as I possibly can. (Applause.)

But on such a theme it is impossible to be calm. Unless we remember we are in bonds with the slaves – unless we feel ourselves the victims of the oppressions and sufferings which they endure, and unless we see with their eyes, and respond with their pulsations, it is impossible truly to sympathise with the slaves of America. I will be as gentle as I can – you must pardon something to the spirit of liberty.

I know, in assemblies like this, there are those who lie in wait to catch if possible a wrong word; but I do not want to please such men. What I want is, that I may speak the words that may be given to me in the spirit of truth and in the love of it. What I want is, to beware how I am a respecter of persons – how I shall speak on this subject without exciting the prejudices of the people, and without compromising the standard of rectitude, which God forbid I should do to win the applause of any man in the world. (Immense cheering.)

Now, I want to refer to another document in the Guardian newspaper, and I am much obliged to the Editor for having copied a part of the speech I lately delivered in Exeter Hall. He seems to think it will excite a prejudice against me as the representative of the American slaves; but I do not believe it will have such an effect; and I wish every newspaper in the world would copy that speech. My observations, as quoted in the Guardian, are as follows:–

He complimented Mr. Hinton in having introduced a motion for the exclusion of the slaveholders, but it did not pass. One would have thought they would soon have resolved the subject. But they appointed a large committee to consider the subject. The committee met; solemn prayer was offered that they might have Divine direction. Several persons engaged in prayer, and implored the direction of God. Then after so much prayer, a number more persons were added to the committee. Now, he denounced all this praying as a solemn mockery before God. In his opinion, if they had done their duty, and had remembered those in bonds, as bound with them, they would have no need of asking God what they should do. Why all this delay, if they were not attempting to wrap up the question? The American delegates ought to have been more decided than any other men, for they held the doctrine that all men were equal; and yet they pretended they had no light from Heaven, and to seek Divine direction. He denounced this language as downright blasphemy.

Sir, I did denounce it as such in Exeter Hall. (Loud cheers.) I denounce it as such here, and wherever I go I will denounce it in the same language, and in the same way that I did in London. (Renewed cheers.) What! men needing light from Heaven to know what they shall say or do with three millions of the human race before them in chains – deprived of the Gospel of Christ – denied the marriage institution – and made marketable commodities! Why, if ever there was a body of hypocrites assembled together under heaven, it was the Evangelical Alliance. (Tremendous cheering, mingled with a few hisses.)

The old serpent generally hisses when his head is bruised. (Cheers and laughter.) What light did they need? What additional light was it in the power of God to give them? None. They were human beings, and God had given them human feelings and affections, and had required them to love their neighbour as themselves, and had enjoined upon them, ‘Whatsoever ye would that men should do unto you, do ye even so to them.’ Had they not the Bible in their hands? Did they not come up at the call of the spirit of God? Did they not come up for the express purpose of redeeming mankind? And, therefore, in respect to these American delegates, no language could describe their baseness and hypocrisy. (Hear and cheers.)

Never, I say, since the world began, was there anything which could be a parallel to it. They came from a country where, for seventy years, the American people annually declare to the whole world, in the presence of God, ‘that they hold it to be a self-evident truth, that all men are born free and equal, and that every individual has an inalienable right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness;’ and yet when the question of the liberation of three millions of the human race comes before them, they profess to be in profound darkness. It was a very intricate and difficult question, and they must have more light. Light! the rogues did not need light. What they wanted was this – two grains of honesty, and half a grain of humanity. (Great cheering.) I am likewise accused of saying, that –

If a man tells me he finds sanction for slavery in the Bible, if you could find slavery upheld in his Bible, I would put it in the fire. (Cheers.) Slaveholding is not setting a man free, but holding him in bonds. Let him beware how he makes the Bible sanction his crime. If your God allows men to be made beasts of, then your God is my devil.

I did say so; and I glory in it, that, if their God allowed men to be made beasts of, then their God was my devil. Why, that is simply to say we are in Glasgow to-night, or that two and two make four; and this is gravely put into the Guardian as something to terrify people with.

Now, friends, has God made us for liberty or not? Does any man want to be a slave? ‘Who so base as be a slave, let him turn and flee!; Yes, father, don’t want to be a slave – you, mother, don’t want to be a slave – you brother, sister, husband, wife, child, do not want to be slaves. You abhor the very idea of being made slaves of, and never would submit to being made slaves. (Hear, hear.) How does this happen? There is something in the breast tells us that slavery is from beneath, and never came from above. Why, the American slaveholders themselves have settled the question. ‘It is a self-evident truth,’ they say, ‘that God has made all men free and equal.’ What is self-evident needs no demonstration. It would be a waste of argument indeed to make this plain way any plainer. Then, I say, if this be so – if we cannot be willing to be made slaves of until our intellects are blotted out, and until our hearts are taken from us, then any man gets a book, I care not by what name it is called, and assumes from what he finds in that book, that you and I should be made slaves of, I will put that book in the fire, if you do not; and I will say to the person that God never wrote that book – I will say it is an imposture, and I will call upon every instinct of the human heart to bear testimony that it is so. Can it be conceived that God made man with capacities only a little lower than the angels, and yet commanded that we should be made slaves of, and marketable commodities? It cannot be, and therefore I say again, that if any man makes out that the Bible sanctions slavery, then I will tell him that his Bible is of the Devil and never came from God. (Hear, hear.)

But I have been endeavouring to maintain for twenty years that the Bible is a glorious anti-slavery volume; and from that exhaustless armoury I have taken my weapons to fight the battle of the slave. From its pages I have drawn my best arguments in favour of the truth of the principles which I uphold. (Applause.)

The charge which I bring against the ministers of religion in America is, that as a body they are atheists. They do not believe the Bible. They have no regard for it. He who loves the Bible for one man – for himself – loves it for every man – for the whole human race. (Cheers.) When I see men conspiring to prevent millions of the human family from having the Bible, and making it a penitentiary offence for any one to furnish the Bible to those suffering millions, I feel they do not believe the Bible. (Hear, hear.)

I am charged with being an atheist, but they are reverend atheists, and all the worse on that account. God never made a tyrant or a slave. God never made a pro-slavery Bible, and therefore I do not own the god of those who endeavour to prove from the Bible that He sanctions the enslavement and degradation of the human family.

In regard to this matter of the pro-slavery Bible, I have before me the last number of the Congregational Magazine, in which there is an article from the pen of Dr. Wm. Alexander, which entirely coincides with my views, and I presume he stands well in this city as a christian man.3 (Hear, hear.) I am not aware that he labours under the imputation of being an infidel, and although I am not at all anxious to bring forward that gentleman to take any part of the odium which attaches to me from the views which I entertain, I am not ashamed of the Dr. in this particular, and as I believe he will not be ashamed of me, I wish to present him to you on this occasion, and see if he does not confirm every word of mine as to a pro-slavery Bible not being from God.

After reading from the article in question, he continued – I hope the Guardian will put the Rev. Dr. Alexander in the infidel list next week. Who are making infidels? Who are bringing the Bible into contempt? Such papers as the Guardian and Warder, and such persons as the leaders of the Free Church, who are giving the right hand of fellowship to those who take away the Bible, and will not allow it to be used by those under their control. (Hisses and cheers.) I do not wonder those friends hiss – they are ashamed of the conduct of the leaders of the Free Church, the whole of whom should be hissed out of their places. (Cheers and laughter.)

After reading another extract from the article, he said, ‘The head and front of my offence hath this extent; no more.’

[SABBATH OBSERVANCE]

Then in regard to another matter of some importance, by way of explanation, I am reported to have said, that, ‘It was wicked in the Alliance to class men who did not keep the sabbath holy with drunkards,’ &c. This language is put into my lips. I used no such language in Exeter Hall. I want men to keep the first day of the week holy unto God. They are bound to do it; and I want them to keep every other day of the week as holy unto God, and they are bound to do it. No day ought to be kept in an unholy manner; but in the impressive language of Paul, ‘Whether we eat or drink, or whatsoever we do, we should do all to the glory of God.’

Now, as an effort has been made, wickedly and maliciously, to stir up the prejudices of the people of Scotland on the subject of the sabbath – as the subject has been dragged into the movement by the enemies of the abolitionists, and not by the abolitionists themselves, I beg to say a word or two in explanation of my views, so that the cause of the slave may receive no injury from that quarter. A few days since, I was in Edinburgh, and some person took the liberty to send me a letter in reference to this matter of the sabbath. The writer says,

I should like to know how you and Mr. Wright have given forth those sentiments at anti-slavery meetings. Your doing so is not only contrary to the manner in which anti-slavery meetings should be conducted, but you should have been aware that you were outraging the feelings of your auditors, in giving rise to the idea, that you took advantage of these meetings to disseminate your heartless heresy. So satisfied am I on the point that your views find no sympathy in this country, that, if the question was put, ‘Whether shall slavery continue with all its horrors, or the benign influences of the sabbath be discontinued?’ the former would be carried unanimously.

I should like to know how the benign influences of the sabbath can exist in a land of slavery. The letter-writer maintains that the two are compatible, and that sooner than have the sabbath infringed upon, the people of Scotland would rather have slavery and all its horrors. Then they would prefer God’s creatures being transformed into fiends. Then they would prefer to become like wild beasts, to tear and rend those they were formed to love. If this is not the case, then it shows that the writer does not know what he is about, and that he needs some farther light on the matter. (Cheers.)

I am not here to go into any argument in regard to my views on the subject of the Sabbath. Give me a proper arena, and I will meet any man on Scriptural ground with regard to the validity of my views on the subject. I profess to believe in the Sabbath. I profess to be as orthodox on the subject of the holiness of the first day of the week as John Calvin, Martin Luther, Philip Melancthon, Rogers, Williams, Penn, Fox, Barclay, and Paley, with many others it is unnecessary to enumerate; and all I have to say at this time is, that if for the views which I entertain on the subject of the Sabbath, I ought to be discredited and sent down below, I beg that Luther and all who framed the Augsburg Confession of Faith go down with me – that is all. Oh! the impudence of those who first claim infallibility on this Sabbatical question – who assume their views must be right – and then give over to perdition all who differ from them.

What is the fact with regard to the Sabbath question? We have in America, and you have here, people called Seventh-day Baptists. They maintain that the seventh day, and not the first day of the week, is the Sabbath of the Lord, and with the fourth commandment in their hand, challenge their opponents to show that the Lord’s day has ever been changed. Then we have those who believe that the first day of the week has been substituted instead of the Jewish sabbath. Both believe they are right, but shall either party give over the other to everlasting torments, because they disagree on that matter. Then we have many others who entertain different views, such as, that under the new dispensation of the law, they should forget all about time as time, and be at all times in the spirit of the Lord – not waiting for a week to roll round to keep a Sabbath to the Lord.

I do not vindicate any of those views; but amidst such contrariety of opinions, is there not scpe for Christian charity, and good reason why we should not sit in judgment upon one another about an outward observance of the Sabbath? I say again, that I hold the same views as the reformers and martyrs of old; and I say this, that you may have your minds disabused in regard to my entertaining any notion derogatory to the holiness of the Sabbath. Almost all have heard of the French Jacobins, who abrogated the seventh day and set the tenth day in its place: and, therefore, when the charge of holding unorthodox views on the subject of the Sabbath is thrown out indiscriminately, those who entertain them are apt to be classed with the French Jacobins, who tried to degrade religion, whereas the individuals I refer to assume a higher view of Christianity, and try to raise the standard, and not to bring it down.

In one word, the amount of the difference is, the difference between Moses and Jesus Christ. It is an old cry. It was raised 1800 years ago – ‘This man is not of God, he keepeth not the Sabbath-day.’ It is the Chief Priests, the Scribes, and the Pharisees who are raising this cry, because we make use of this day for the purpose of raising me out of the pit instead of beasts., (Applause.)

The report goes on to state –

The Rev. John Preston, Baptist Minister, Euston Square, here rose, and said he was a member of the Alliance, had sat in 19 sessions, and therefore understood it. He had doubted, and more than doubted, during some parts of Mr. Garrison’s address, whether he were a friend of Christianity. When he came to that meeting he did expect to hear strong things uttered against the Alliance, but he did not expect to hear Christianity in general undermined, and prayer to God ridiculed.

Now I will say nothing about the ridiculous plight the Rev. John Preston got into when he got upon that platform; I will not quote what I did say word for word, as it is reported in the London Patriot, but I will give the reply of my friend, Mr. George Thompson , to the foul imputation of that imprudent man:–

My beloved friend, William Lloyd Garrison, has been charged with ridiculing prayer, and seeking to undermine Christianity. He did neither the one nor the other. He denounced a counterfeit Christianity, with forgets the slave in its prayers, which fellowships the slaveholder, which talks of love and has not pity and he preaches a Christianity which opens the prison doors which binds up the broken heart, which breaks every yoke, and sees a brother and a man in the meanest and most afflicted wretch that was ever left to perish by the way, while the priest and the Levite passed by on the other side. (Cheers.) His ridicule of prayer was not the ridicule of the prayer of the publican. ‘God be merciful to me a sinner,’ or of the soul, agonising for those in bonds as bound with them; but that prayer which asks God to direct men how they may escape from the consequences of their own abandonment of righteousness, without repentance, and the doing of works meet for repentance. I will remind the friend who brought this charge, that a greater than William Lloyd Garrison once said, ‘Woe unto you, Scribes, Pharisees, hypocrites, for ye tithe mint and anise and cummin, and neglect the weightier matters of the law, – judgement, justice, and faith. Ye bind heavy burdens, and grievous to be borne, and will not touch them with one of your fingers. Ye devour widows’ houses, and, for a pretence, make long prayers. [‘] (Loud cheers.)

Sir, in America, they do something worse than devour widows’ houses; they devour the widows themselves, and then pray to God for direction how to treat a human being. I ridiculed such prayers. (Cheers.) I said they were blaspheming before God, and I will continue to say to wherever I may go. (Great applause.) I stand up backed by John Knox, a man who did not talk about using ‘a little circumlocution,’ when he had to do with the Devil and his works, but who called a fig a fig, and a spade a spade. I will give you his words as they fell from his lips, and strange as it may seem, the passage I am about to quote is the motto of the Witness newspaper. It is as follows:– ‘I am in the place where I am demanded of conscience to speak the truth, and therefore the truth I speak, impugn it whose list.’

Now. I have got another excellent motto from another organ of the Free Church, and not entirely unknown to you. The motto of the Guardian is, ‘The people of Great Britain are a free and a religions [sic] people, and, by the blessing of God, I will lend my aid to keep them so.’ This paper is now denouncing the friends of liberty in America, and is endeavouring in this manner to preserve the liberties of the people of Scotland. (Hear.) The paper which justifies all manner of cruelty involved in slaveholding talking about looking after the religion of Scotland! ‘Send back that money,’ and then look to their liberties. (Great cheering, mingled with a few hisses.)

Never mind the hisses; let us hear them as distinctly as possible; they are music to my ears.

I was in Dundee a few days since, and when I arrived there, I found a foul attack upon myself and the cause which I represent in the Dundee Warder; and amongst other extraordinary declarations contained in the article, I found the following; and when I read it, I think you who are impartial witnesses here to-night will admit a case of effrontery more striking was never given to the world. The Warder says, ‘that neither the Free Church, nor any individual member of it has ever defended slavery or slaveholding on any ground whatever, far less by any reference to Scripture.’4

Now the whole controversy with the Free Church is upon this, – Is slaveholding under all circumstances a sin or not? The Free Church maintains that it is not; that a man may be a christian slaveholder; and it runs to the Bible and tries to be a christian slaveholder; and it runs to the Bible and tries to prove its position is a scriptural one; and yet this Dundee Warder has the impudence to say that it never attempted to vindicate slaveholding. (Cheers.)

How should we wonder at this? Men who go and get blood-stained money to build their places of worship with, will do anything – when convenient. (Great applause.) If they will, to get money, strike hands with thieves, they will lie to save themselves from the exposure of the world.

Now, the question at issue is, Does Christianity forbid all slaveholding, or does it not? Was Jesus Christ a slaveholder or a slave-trafficker, and are his followers to be the same? The churches in America with which the Free Church is in connection, hold that opinion and the Free Church says they are Christian Churches, and welcome their ministers to their communion and to their pulpits. In the same way, if the Free Church was asked if slaveholding is not a sin, it would tell you – sometimes, but not always. In the first place, slaveholding is not a sin when a Doctor of Divinity is the man who holds slaves. If he was some poor wretch who does not make any pretensions to piety, it would be atrocious; but it is your Doctors of Divinity who can hold slaves with impunity, because ‘A saint in crape is twice a saint in lawn.’ (Cheers.)

That is one way, and I will give you a specimen of those D.D.’s who can hold slaves innocently, without tarnishing his christian character. Just before leaving Boston for this country, a fugitive slave came and put a letter into my hands, and said, ‘I want you to take this letter to the people of Scotland; I want you to read it to them; and I want you to ask the people of Scotland what they think of the humanity or piety of a Doctor of Divinity who could pen such a letter as this.’ The letter is addressed to a person in New York, and is in reference to a runaway female slave.

Mr. G. here read the letter referred to, which requested the person to whom it was addressed to put a description of the writer’s fugitive slave into the hands of a police officer, that he might apprehend her. The paper, in addition to mentioning the mental characteristics of the fugitive, contained a description of her personal appearance, which was given with disgusting minuteness, and could scarcely fail of raising some suspicions as to the purity of the writer’s thoughts.

Having finished the letter, Mr. G. continued – He is just the very man for the Free church – the very man for Dr. Candlish and Co.; he is willing to quite all claim to his slave for a consideration. As to the person who was to send her back, Dr. Cunningham would have had no difficulty in vindicating him on the ground that Paul sent back Onesimus to Philemon. (Great cheering.)

Now, I ask, if any language can be found in our tongue to describe the unblushing villainy of such a man as this. (Hear, hear.) Claiming to be a divinely ordained minister of God, and yet offering rewards for the capture of his slave, that he might again put her into bondage. There is no language can describe such wickedness. Yet he is the very man for Dr. Candlish – the very man for the pulpits of the Free Church, and will be the very man for such a body, until we get the money sent back. (Cheers.)

Again slavery is innocent, when the Free Church gets supplies from the slaveholders. If they did not get the supplies it would be a different thing, but so long as they put money into her coffers, of course it must be innocent. It is also innocent to hold slaves in bondage, notwithstanding the injunction to ‘break every yoke and let the oppressed go free,’ in circumstances which God did not calculate upon when he gave that command.

There is another case in which slaves may be held innocently; somebody else may do wrong, if we do right; therefore we ought not to do right. When a slaveholder emancipates his slaves that is right, but we are told the law, forsooth, will take them up, and they can sin much more economically than somebody else could. Why, what have I to do with another man’s wickedness but to rebuke it. Because I say to another man, ‘You are my brother; your chains shall fall; I stand to proclaim you free and not a slave;’ and then a body of unprincipled men come in and seize the victim, am I responsible for that deed? I ought to do what I have done. They ought not to do what they have done. (Applause.)

Dr. Cunningham has stated, that unless slaves are retained in service in the slave states of America, that the good Christians would have to take Irish papists into their families. There you have a case of innocent slaveholding. Irish papists are not to be employed, therefore never take them into service. Treat them as lepers; do not give them any encouragement , and then we shall convert them over to protestantism. Do not attempt to emancipate the slaves; that is gravely put forth by Dr. Cunningham as a very solemn reason against it. (Cheers.)

There is another case in which it is very clear that slaveholding is innocent – the case of every American who declares that it is a self-evident truth that every man is born free and equal. We are told that slaveholding is not sinful under all circumstances.

Sir, 1800 years ago Christ was born. He came to proclaim the acceptable year of the Lord; he proclaimed the redemption of the human race. Yet it is necessary to strive here as in America to convince men that it is a sin to make a beast of their fellow men. The sin has been denounced for 1800 years. Paul was the first who preached an anti-slavery sermon, when he announced at Athens that ‘God hath made of one blood all the nations of the earth.’ What will these libellers say to that? (Cheers.)

How painful to think that great truth is not fully recognised the people as Paul did, that they are worshipping an unknown God, and do not believe in the brotherhood of the human race. Slaveholding is not under all cases slaveholding. What is a cabbage under all circumstances but a cabbage? What is a hawk but a hawk? What a dolphin but a dolphin, or is it sometimes ‘very like a whale?’ (Laughter.) What is horse-stealing at all times but horse-stealing, if it is not burglary some times? What will the Free Church be at all times until the bloody bawbees be sent back? (Cheers.)

Slaveholding, if there is any meaning in words, is holding a slave. It is not holding a free man, nor setting him who is in bondage free. Slaveholding is not non-slaveholding. It is slaveholding and holding a slave. What is a slave? He is not a freeman, of course. He is a thing; an article of traffic, which may be bought and sold, and used as property. Then the slaveholder is, under all circumstances, a man-stealer; therefore there can be no innocent case of slaveholding.

Oh! but the laws, says Drs. Candlish and Cunningham. Well, what of the laws? Either these laws are righteous, or they are unrighteous. If they are righteous laws, why should they be referred to as a grievance? If it were not for these righteous laws they would do something – something very bad of course – for it is the righteous laws which restrain them from doing the deed. Well, if they are unrighteous laws, what then? If they oppose the commands of God, what then? Why, they are to be trampled under foot – that is all. (Cheers.) They are to be set aside at once as impious, and not to be obeyed, be the consequences what they may, and the eternal law of God put in the place of them. (Cheers.) Either those slave laws are bad, or they are not. If they are bad, being unrighteous, those who obey them are unrighteous men, and may not be recognised among the followers of the Lord. If they do not obey them, then of course we are not speaking of those who disobey the unrighteous laws, and hence we desire to keep by the issue, and have no red herring thrown in our way, to lead us off the track.

I am called an infidel. That is a red herring. Either a man is a slave, or he is not. If he is a slave, he who holds him as a slave, is a robber of his brother man. If he do not hold him as a slave, we have no controversy with him. How are human laws framed? By Parliaments and other bodies of men; but the laws you are under are of God.

How was it in the case of Daniel? A law was passed desiring him not to pray to God. He had been in the practice of praying three times a day to God with a loud voice, and with his windows open. His enemies desired to destroy him; therefore they got an edict put forth, making it an offence to pray to God. What did Daniel do? If he had been Dr. Candlish I will tell you what he would have done. He would have said, ‘I cannot disobey that command – it is a law. But there is no use of praying aloud to God. I will use ‘a little circumlocution.’ I can as well pray secretly to Him as audibly; I can obey God and yet obey the law.’ That would have been Dr. Candlish’s reasoning. (Hisses and cheers.) Let them hiss at him – why should you object to it, friends? (Cheers.) Now, Daniel said, ‘I will pray to God as I have been wont to do.’ It was not necessary that he should open his windows until the law came; then it became necessary as a religious duty, and he would have been false to his God, and never could have prayed to God in a right state of mind, if he had complied with the law. (Hear, hear.)

We are told that slaveholding in America is shamming – that the slaveholders are humbugging the state – that they are slaveholders in form as the law requires it, but that they are not so in reality. (Hear, hear.) Now, I do not believe that, for no Christian would acknowledge such a law. He would say, ‘I am an honest man; I am against the law, and I will not obey it[.]’ (Hear, hear.) When Jesus was about to be crucified, they talked about the law, and when the slave is to be retained in bondage we hear the same thing. But who make the laws? The slaveholders themselves, thus tying themselves up to their impiety.

If there is anything in their prayers, let the slaveholders give their slaves passes to Canada, where they may stand up as freed men far from their pursuers. If slaveholding be not in itself sinful, I ask you how you do not allow slaveholding in Scotland? You take it for granted that no man can be an innocent slaveholder. Brother Cunningham may see somebody he wants to benefit, and therefore desires to make him a slave. But you will not allow him, because you say it would be a crime. What have you done with regard to African slaves. You say, that if a man goes and buys a slave he shall be branded as a pirate, and shall be hanged. Why do you do this? Why not allow men to judge for themselves, if they may innocently enslave a fellow-creature? You have not left a single slaveholder alive in the West Indies, and there is not a single slave there. That is assuming that not a single man may hold another man in bondage. Now, that is the issue with the Free Church, which they have not met, and which they cannot meet.

Then again, the Americans settle the question, by saying that ‘It is a self-evident truth that all men are born free and equal.’ When I remember that the Americans are the people who put forth that declaration, I blush to think that any man in Scotland would try to make out a case of innocent slaveholding. Do you mean to condemn the Society of Friends, because they will not allow a slaveholder to be a member of that society? Is it not the glory of that society that they keep so sublime and true a position; and if every other religious society would take the same position, where would slavery be? (Cheers.) Nowhere, or in the abstract, where so m any people put it already.

‘Oh!’ said the Rev. John Burnet, ‘I have heard much about slavery in the abstract, and I have gone over globes and maps to find out where the land of abstraction is; but wherever it is, slavery must be horrible indeed, since even slaveholders execrate it with all their hears.’ (Great cheering.)

You do not condemn the Friends, yet, by this logic you ought to condemn them, for they are in the midst of slaves, and if slaves may be held innocently, they ought not only to keep them, but to multiply them for their good. Will any man in Scotland condemn the sturdy covenanters in America, who are exhibiting such a glorious example to the world. (Cheers.)

After a fifteen years’ struggle against slavery, a number of churches have now a rule that no slaveholder can be admitted to Christian fellowship, and do you mean to say the occupy a false position? Do you mean to condemn the course taken by the non-slaveholding churches in America? Yet if you mean to go with the Free Church, and the Evangelical Alliance, you must do so, notwithstanding that it hath been said – ‘He who stealeth a man and selleth him, or if he be found in his hand, he shall surely be put to death.’

They tell us that slaveholding existed under the old Levitical code; but men blaspheme God who say that he allowed that dispensation. God never brought plagues upon Egypt because of the Israelites being held in bondage, and then gave those he had redeemed liberty to become slavetraders, and slaveholders.

One thing more, and I conclude. It is an extraordinary spectacle to God and to the world to see that, while America is becoming anti-slavery, Scotland is becoming pro-slavery. This is the position of the two nations at the present era. A few years back we were all slaveholders in America. After a long and fearful struggle, we have now in a great measure redeemed the nation; and having put on our armour, we are going on conquering and to conquer. But alas! within the last two years a fearful change has come over the people of Scotland, and Scotland, which was once anti-slavery, is now fast becoming pro-slavery, and men in the provincial towns are running to their Bibles to justify slavery from the Scriptures. Why, it should excite alarm in the breast of every man who wishes to see Christianity rule in the world.

When I speak of men running to their Bibles for arguments in support of slavery, of course I speak only of a class, for I bless God the whole people are not contaminated – I bless God there are still many true to the rights of man; and I do not believe that the church – falsely called Free – is the true Church of Scotland, or that it fairly represents the sentiments of the people of Scotland in regard to this important question. (Cheers and hisses.) All they can do is hiss. They would like to make slaves of you, but they cannot. They would like to make you the apologists of manstealers, but they cannot, and they are very much distressed about it.

The heart of Scotland is still sound on this question, and I call upon you to bestir yourselves in the name of God and of humanity, and see to it, that the money is sent back to America. (Great cheering.) Come to this resolution, that either the money must go back, or the Free Church shall go down – (applause) – and if she must go down, because of her blood-guiltiness, then the Free Church of Christ will stand all the more gloriously vindicated, and there shall be peace and purity throughout her borders.

But remember, it is not enough that you be free yourselves, –

Old Bannockburn hath yet a tongue,

And Bothwell is not dumb,

And voices from your fathers’ graves,

And from the future come:–

They call on you to stand your ground –

They charge you still to be

Not only free from chains yourselves,

But foremost to make free.

Mr. Garrison resumed his seat amidst enthusiastic applause.

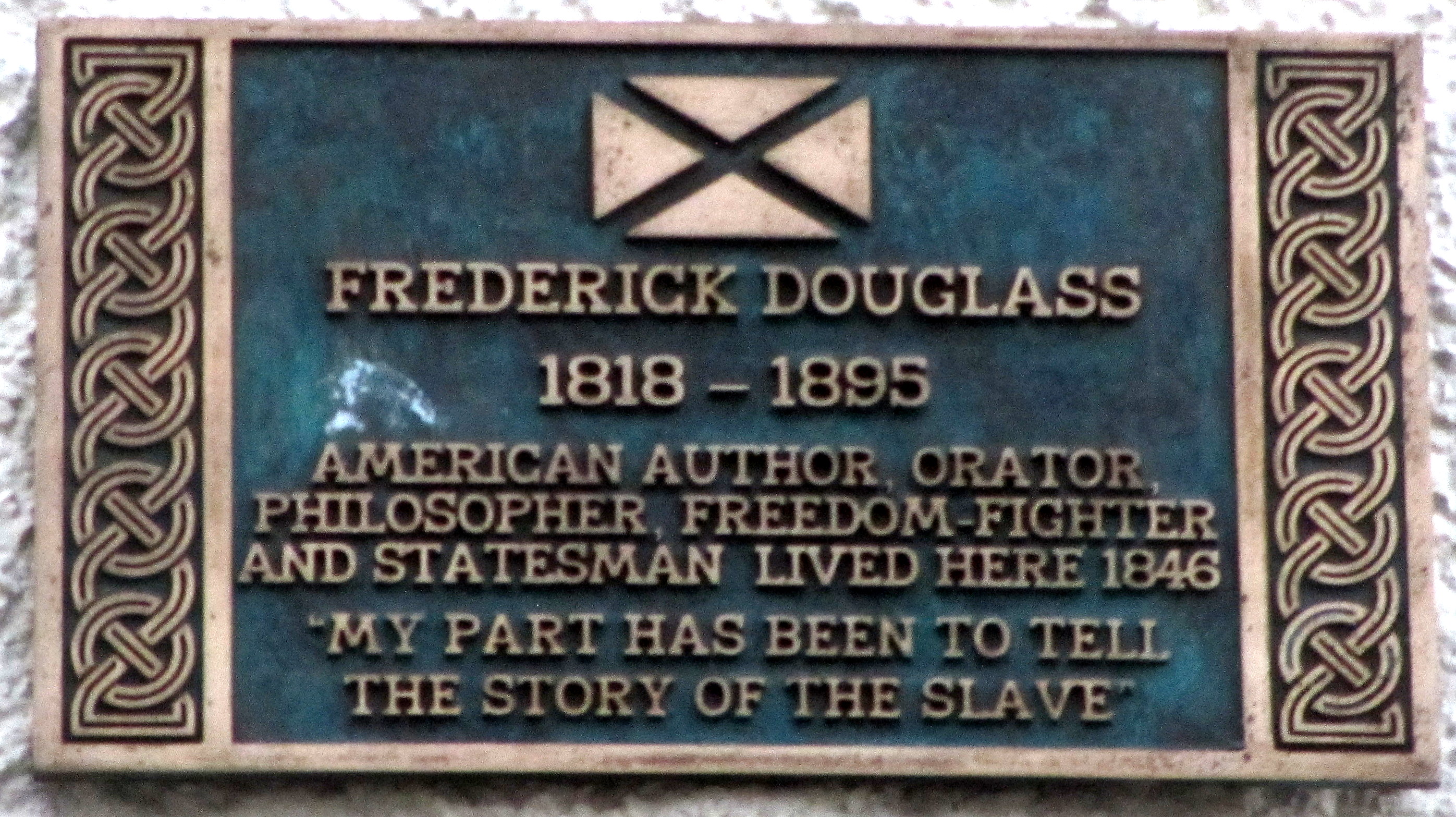

Mr. FREDERICK DOUGLASS, who was received with applause, said, I feel very glad to be in Glasgow, especially to have an opportunity of speaking to you on the subject of American slavery. It seems that the fight for the abolition of slavery in America, like the battle for emancipation in the West Indies, is to be fought upon British soil. Both the friends of slavery and its enemies have appeared in this land, and the community are fast taking sides with the one and the other party of deputationists from the United States.

The deputation from the anti-slavery party is small; the deputation from the pro-slavery party is large – very large. The one and the other met not long since in the city of London. The one calling itself the Evangelical Alliance, and the other calling themselves the reviewers of the Evangelical Alliance. (Cheers.)

There are but two parties in the United States on this question, neither can there be long more than two in this country in reference to it. There are but two parties in the United States, I repeat, the slaveholders and the anti-slaveholders – the friends of the slave and the enemies of the slave. We are two – there is no middle ground. There is no serving anti-slavery a little and pro-slavery a little. There is no worshipping at the shrine of slavery and at the shrine of liberty at the same time. There is a strong line of demarcation drawn between the abolitionists in the United States and the anti-abolitionists – that line is becoming more and more distinct in this country, and the more distinct it becomes the better. The sooner we learn who are the friends of freedom, and who are not, the better for the cause of emancipation in this country. (Cheers.)

[THE DECLINE OF SCOTTISH ABOLITIONISM]

Not six years ago there were many in this city who did not hesitate to come forward and avow themselves the uncompromising advocates of emancipation, who were called Rev. Doctors of Divinity, and where are they now? They are among the missing. They have ceased to work with us; they have ceased to strike hands with the abolitionists. This platform was once the arena of the eloquence of such persons as Dr. King, Dr. Wardlaw, Dr. Robson, and other eminent Doctors of Divinity in Glasgow. Where are they this evening? One of the slaves for whom they appeared to plead stands here this evening to ask after them. (Great applause.)

Well do I remember how my heart throbbed with gratitude to those men when I read their speeches on the subject of emancipation. I remember how my heart was thrilled when I read the speeches of Dr. Wardlaw and those of George Thompson in relation to this subject. But where are they to-night? Where is Dr. King, Dr. Wardlaw, and Dr. Robson? Have the salves in the United States given these gentlemen any offence? Have the slaves behaved in any manner to justify them giving up the cause of abolition, and abandoning them to their tyrant masters? (Hear, hear.) I think not; but if they have, these gentlemen should tell us what they have done to lead them pass them by on the other side. (Cheers.)

[THE EVANGELICAL ALLIANCE]

My object in rising, however, at this period is to say a few words about the Evangelical Alliance. We have had some meeting in this country since I had the pleasure of addressing a Glasgow audience. A number of things have transpired tending to give the question a different complexion to that which it wore when I was here before. Since I was here, the Free Church General Assembly was held at Canonmills. Since I was here, the Evangelical Alliance has held its sittings. Since I was here, the World’s Temperance Convention has met in London. Since I was here, the United Secession Synod has declared that it would countenance no Christian union with slaveholders. (Cheers.) Since I was here, the Relief Synod has declared in favour of non-Christian fellowship with man-stealers. (Applause.) Since I was here, the Irish Presbyterian Assembly has denounced slaveholding as man-stealing.

All these and other circumstances have transpired, tending to give a different complexion to this question to what it presented when I was here some months ago. But one of the principal things which has taken place was the holding of the Evangelical Alliance.

The Evangelical Alliance is a high sounding title. Let us trace the history of the connection of the slavery question with this distinguished body. A preliminary meeting of this Alliance was held in the town of Birmingham, and before that meeting came the question of American slavery, and the question as to how the Alliance should regard American slaveholders, or slaveholders, no matter from whence they came. The question, I am told, was sharply debated, and the Rev. Dr. Candlish brought forward a resolution embodying the proposition, that slaveholders be not invited to attend the Alliance. This resolution was agreed to, and was soon published in this country and in the United States. Slaveholders and non-slaveholders saw it. The former were well acquainted with the fact, that they were likely to be placed under the ban of exclusion if they attended the Alliance. It was not that slaveholders be excluded from that Alliance, but that they be not invited to that Alliance.

With this resolution looking them in the face, some seventy ministers left the United States for the purpose of attending the Evangelical Alliance, then to meet in London on the 18th of August last. They came a united body. There are no two parties in America among the friends of slavery. They came to London, and the Evangelical Alliance was summoned together. They met together in convention, and one of the first acts of that Alliance was to shut out the light – they excluded reporters, which was to say, in effect, ‘We are about to do an act – we are about to have such deliberations – such devil’s work is to be done as it will not be safe for the world to see. We will exclude all reporters; if we have deeds of diabolism among us, we will at least shut out the eyes of the world.’ What would have been thought of a body of Roman Catholics doing this? It would have been said that it was perfectly in keeping with the practices of that body; but I will not repeat what the people say about the Evangelical Alliance for doing the same thing. Did they look as if they desired to be inspected of men? Why, Christians, in the language of our blessed Saviour, are represented as cities set out on a hill; but the very first thing the members of the Evangelical Alliance did, was to put themselves under a bushel, to extinguish from them the light of investigation. (Cheers.) But although the discussion could not be had in full, there were some in the camp who reported the meetings of the Alliance.

During these sittings there was a great outpouring of love: the American brethren loved the British brethren, and the British brethren loved the American brethren. (Cheers and laughter.) Never was there such demonstration of Christian regard, of Christian love, and of Christian sympathy. In the midst of all this the question arose, What shall be our basis? On what terms shall individuals be admitted into the branches of our Alliance?

They agreed to a certain form of creed; but there was a Dr. Hinton among them, a man tinctured a little with the spirit of anti-slavery. He knew that there were certain men in the United States who held precisely the same views of the basis recommended, and who made as high pretensions to evangelical faith as the Alliance itself, but he knew these men were slaveholders, and he desired to add to the basis a clause which would prevent slaveholders from being admitted into the Alliance. Greater agitation could not have been produced by the throwing of a bombshell into the midst of the Alliance itself than the raising of this question. It produced the greatest possible excitement. Those brethren quo loved so much, and who had come, many of them, 3000 miles to embrace each other, were in arms in an instant. The bond of their unity had burst asunder. Angry discussions arose: and the evangelical manstealers would not unite with the others if slaveholders were excluded from that Alliance. Dr. Patton said, he had come 3000 miles to attend the convention; and when he started from home, he had no idea that they intended to make a British child of it. He had no idea of its being made an anti-slavery Alliance. He need not have been afraid, as you will see.

The discussion grew angry. The American brethren can be warm and speak out strongly. They deal in brimstone, fire, thunder, and lightning, and such figures of speech. (Cheers and laughter.) They have not learned, as Dr. Candlish has done, to use ‘a little circumlocution.’ (Renewed laughter.) They said to the Alliance, if that amendment of Dr. Hinton’s passes, we must leave the Alliance. They had loved each other very much before. (Laughter.) They loved the Alliance still. In the language of Mark Antony they did not ‘love Caesar less, but Rome more‘ – they did not love evangelical truth less, but slavery more. They said in effect, if you pass a resolution excluding our dear evangelical manstealers from your Alliance, we must go out of it.

Well, at this point some of the British brethren became faint at heart and pale in the face, and up they rose one after another and spoke in the following strain:– ‘We would exhort our brethren to be calm. We hope that nothing imprudent will be done. We do hope that we shall yet be brought to a judicious decision on this question. Remember the eye of the world is upon us – the eye of Protestantism is upon us – and, what is more, the eye of Rome is upon us. If we should separate on this question, oh! what will become of us. We would, therefore, move that this whole question, be remitted to a committee.’

It was at once seconded, and the question of slavery was referred to a committee. That committee was made up to a large extent of the American deputation – Drs Cox, Patton, and others of the Presbyterian manstealing order in the United States. They discussed the question. They examined it, by day and by night for six days. About the middle of the week, the Rev. Dr. Smythe, of South Carolina, I believe, the gentleman who invited the deputation of the Free Church to the south, and recommended them to the cordial sympathy and aid of the evangelical manstealers of the Union, rose, and begged that the Committee be instructed to take time – not to decide hastily – and in their absence he recommended that the Alliance should pray for the brethren composing the committee, and that they might come to an enlightened decision. This Dr. Smythe is the same Dr. Smythe who gets his living in South Carolina for preaching to a congregation entirely composed of slaveholders – he is the same Dr. Smythe who marries slaves, leaving out the important part of that solemn ceremony, which says, ‘Those whom God hath joined together, let no man put asunder.’ He is the same Dr. Smythe who lives in the midst of slaveholders and slavedrivers, and never opens his mouth against slavery – the same Dr. Smythe who is the unblushing advocate of slavery – if not the actual owner of slaves in America – and yet this Dr. Smythe asks the brethren to pray, and they did pray. (Cheers and a slight hiss.)

I am not ridiculing prayer; I am ridiculing that kind of prayer, and that kind of union which exists in the slave states of America, and which existing in the Evangelical Alliance. We have a great deal of this kind of piety in the United States, and it was very manifest in the Evangelical Alliance. I speak of that Alliance as an injured man – as one whom that Alliance has neglected – as one whom that Alliance has stabbed to the heart, and I will speak out, let who will condemn me. (Cheers.)

Sir, there is a recreant black man in this country going by the name of Clark.5 He went into that Alliance and there denounced the only true friends of emancipation – the abolitionists. If he goes through this country, as I expect he will, for I expect that the Free Church of Scotland will employ him to go about and defend her, as he has the Judas Iscariot impudence to stand up in defence of her connection with the manstealers of America; and I trust he will be informed that I arraigned him here as a traitor to his race, and as representing no portion of the black, or coloured population in the United States.

Let us go to the question before the Alliance. It was a very plain one, namely, whether a manstealer ought to be regarded as a standing type and representative of Christ, or not? The question was, whether the Alliance would throw the garb of Christianity around the slaveholder, or not. It was a yea or a nay. The committee reported, and a resolution drawn up, to the effect that the Alliance was confident that all who are slaveholders would be excluded from the branches of the Alliance, who are so by their own fault or for their own interests. Just as if there was a man living who held slaves for any other person’s interest but his own, or that holding slaves could be the fault of anybody else but the man who held them. This was base and mean; and I find that even the eloquent Dr. Wardlaw who had stood up as the friend of the negro, deserted him, by agreeing to this abominable compromise, men who should have spoken out beyond all others, especially as the United Secession Synod had declared for no union with slaveholders.

This conclusion come to on the part of the committee was for a time quite satisfactory to the American deputation. It was satisfactory in the morning, but unsatisfactory in the evening. They turned themselves round; it was a great improvement on the proposal of Dr. Hinton, but after all it was not what the American brethren wanted, and they refused to consent to this compromise. They demanded that the matter should be re-committed, and proposed that they should go about it in the midst of prayer and fasting, and they actually wanted their dinners. (Laughter.) This produced a wonderful sensation in the Alliance. Such was their zeal for evangelical manstealing and evangelical manstealers, that they could not eat. Their appetites left them, and it was made a matter of awful solemnity that those brethren could not eat. (Cheers and laughter.)

After this the American deputation demanded that every trace of the discussion, and of the resolution referring to slavery, should be erased from the records of the proceedings of the Alliance. Three millions of human beings in slavery, in the American plantations, were imploring the members of the Alliance to open their mouths in their behalf, and to condemn those who enslave them; but the American deputation said, no such condemnation shall appear in the proceedings of the Alliance. Sir, that Alliance acted like a band of infidels rather than of Christians. At the bidding of those American manstealers, the English and Irish, and Scotch members expunged from the record of their proceedings every word of condemnation of slaveholding in the United States. I hold, that no body of men could be gathered together from any quarter in this country but ministers who would have been guilty of this deed. (Cheers.) Amongst no body, however degraded, but there would have been some to speak out in condemnation of slavery. Yet those men of high profession passed by on the other side, and never raised a whisper in condemnation of the system, – in effect saying, as far as the Evangelical Alliance will not utter a word of condemnation against you.’ (Great applause.)

[THE FREE CHURCH OF SCOTLAND]

Let me say one word about the Free Chruch of Scotland; for it has taken shelter behind the Evangelical Alliance, and I want to say a word about the recent General Assembly of the Free Church. I happened to attend the Assembly, and I heard the speeches delivered on that occasion on the subject of slavery, and I heard the thunders of applause at the end of each sentiment, which looked like upholding the system of slavery. I could not before have believed that such sentiments would have received any degree of commendation from any of the people of Scotland; yet in Canonmills I heard the most infamous – the most blasphemous – sentiments uttered amidst applause, in defence of slaveholding, and in defence of the Christian character of slaveholders, which I ever heard in any place.

I heard Dr. Cunningham say that Christ and his apostles would not only have sat down at the communion table with slaveholders, but that they would have sat down at the communion table with slaveholders who had a right to kill their slaves if they would, and never rebuke them. I heard him try to bring the idea that slaveholding is sin, and slaveholders sinners, into contempt, and I am sorry to say that he was heard, by some three thousand in number of an audience, with seeming approbation. The battle of anti-slavery is to be fought here not with infidels, but with the Doctors of Divinity of Canonmills – the God sent, God qualified, and God appointed preachers of the salvation of Christ. Those are the men who stand up as the indefatigable enemies of the down-trodden slave – who stand up in defence of men who drive to toil, to torture, and to death, three millions of their fellow men. (Cheers.)

To prove that slaveholding is not sinful in itself, Dr. Cunningham put forth the following argument. After admitting that Mr. M’Beth had fairly stated the question when he said it was plainly, Whether slavery was not in all circumstances a sin? he said Mr. M’Beth had stated that it was in all cases a sin; but he took the opposite side of the question – he took the ground that it was not always a sin. He thought that slavery might be a sin, and not the slaveholder a sinner. Suppose, he said, on the 1st of June next, the Parliament should pass a law declaring all domestics to be slaves of their employers. I know that I should be a slaveholder, but could any man charge me with sin? ‘Hurra, hurra,’ shouted the Assembly, an innocent case of slaveholding has been made out. (Great laughter.) When they heard him putting the case, and admitting that Mr. M’Beth had rightly stated it, the whole Assembly had solemn faces, and seemed to be very concerned as to what great feat this mighty doctor would perform. When he put forth his argument, however, the enthusiasm was perfectly astounding.

But let us look to the argument and try to test its validity. If it is good on one case, it is good in another. Let us take the case of polygamy – a sin not to be ranked with manstealing, because that, being the greater, comprehends it and other sins. Suppose on the 1st of June the Parliament were to pass a law declaring that all female domestics are to be the concubines of their employers. Dr. Cunningham would be a polygamist; but I ask would he stay in that relation to his domestics? (Hear, and cheers.) I do not know that he would not. I certainly heard nothing in his speech to convince me he might not. Why not? If in the one case, why not in the other? If he could become a slaveholder because the law declared him such, why not become a polygamist because the law declared it to be right? (Loud cheers.) Would Dr. Cunningham’s argument have been received in any other case? In no other; and I maintain you are not safe in the company of such men, for those who will apologise for the stealing of black men, will apologise for the stealing of white men. (Hear, hear.) The man who will steal black horses will steal white ones. (Cheers and laughter.)

The mean-stealers of America are upheld and sustained in their system of plunder by such arguments as that used in the Free Assembly; but I hope the people of this country will see to it that those using them do not go unrebuked. Let not the Warders, Witnesses, or Guardians suppose that the cry raised against the Free Church and the Evangelical Alliance is to be but a nine days’ wonder. We will not be stopped by any impediments that can be thrown in our way. They speak of a decline of the interest on this question; but I would like to see it. I was in Dundee and various other places with Mr. Garrison, where we held meetings 6 months ago, and so far from the interest having declined in that time, it had doubled, and the hearts of the people are as ready to leap up at the voice of freedom as they were before. (Cheers.) They are as ready as ever to raise that cry, which has given the Free Church more pain than any thing else, ‘Send back the money,’ and will keep up the cry, however long it may be, till the money is sent back. (Applause.)

We do not mean to lose sight of the Free Church by talking of the Alliance; and, as an individual, I will not be drive from my course by any thing the defenders of that Church can say of me. They have struck hands with slave[holder]s. I am a slave, and I do not expect, therefore, they will speak well of me. They indorse the Christianity of the slaveholders of America; I do not expect them to indorse mine. They are on the side of the oppressor; I am on the side of the oppressed; I do not expect they will commend me. (Great cheering.) These men have stolen the garb of heaven, the sacred name of freedom, to cover up the deeds of deep damnation of which they are guilty; I am for tearing asunder that garment – I am for revealing the character of these manstealers – and exposing them in their naked deformity. It is not to be expected that they will speak well of my friend Garrison or of me, who come accredited by the tears, and groans, and grateful throbbings of three millions of human hearts in the United States. I look to them for consolation, and not to the Free Church of Scotland.